A Tolkien of My Affection

Computing Across America, chapter 39

by Steven K. Roberts

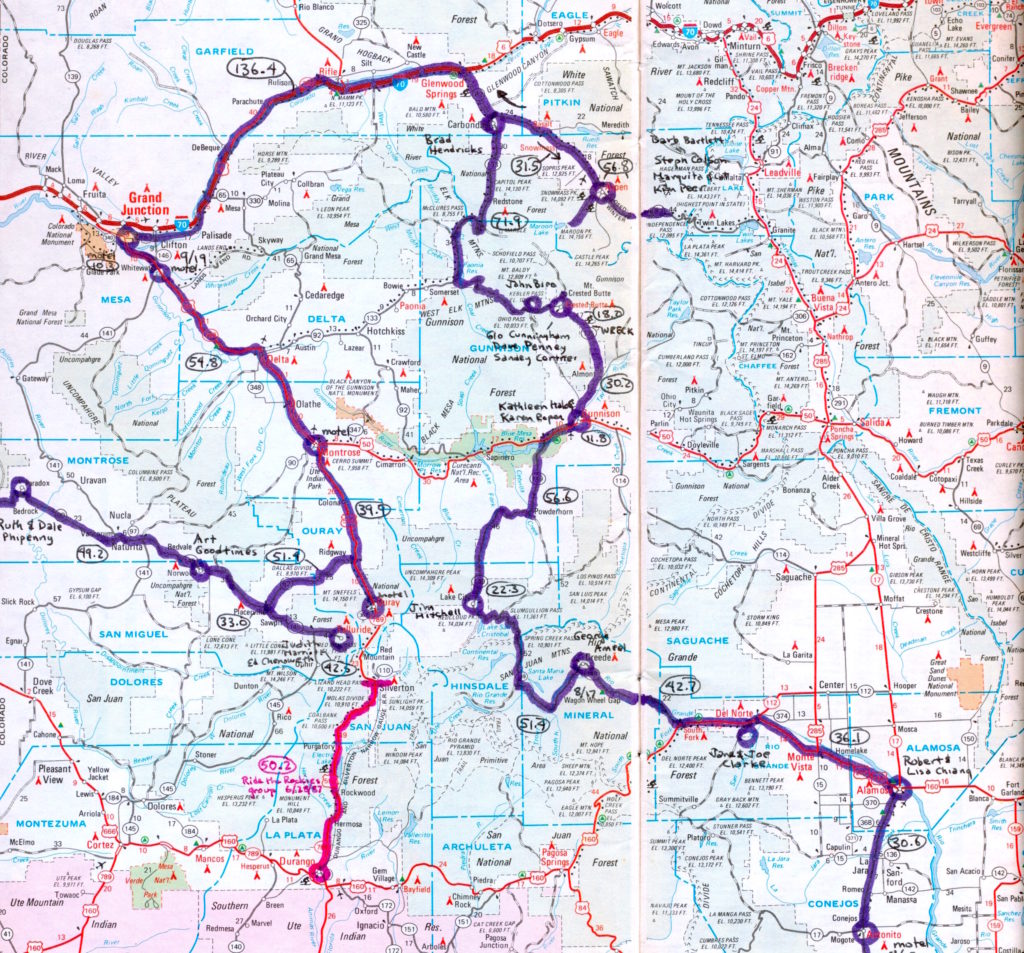

Lake City, Colorado

August 25, 1984

Slumgullion Pass… sounds like something out of The Hobbit.

Kacy Branstetter

There’s nothing like pedaling a 200-pound bike over mountains to give one a profound new respect for gravity. I stood at the summit of 11,361-foot Slumgullion pass and looked out into space, exhausted but triumphant.

The afternoon had been a long slow celebration of the granny gear, an endless succession of switchbacks shared with rumbling Texan campers. I had crossed the continental divide at the comparatively tame Spring Creek pass a few miles before, and took a roadside leak with the delighted thought that my infinitely diluted molecules would someday tumble into the Pacific Ocean.

Climbing the pass… phew. I watched the altimeter needle reach new heights — the instrument aiding me psychologically by preventing that helpless cry of “Oh God, won’t this ever end?” with each new uphill vista. Around me was a deep forest of pine, carpeted in wildflowers, mushrooms, and the thick brown litter of trees.

So there I stood, atop Slum. It was a moment of glory, the highest elevation of my trip, before or since. I felt good: in the thin mountain air I had rested frequently, respecting the task enough to pace myself.

Thunder.

Thunder again — and getting closer. With Lake City only nine miles down the road and half a mile closer to sea level, I pushed off and let gravity take over.

Yikes! A dizzying panorama unfolded before me, a scene of deep convoluted beauty and geologically revealing strata. I kept trying to appreciate it, to catch glimpses of Lake San Cristobal and the 700-year-old landslide that had formed it, but the earth’s pull was at least as relentless as it had been on the other side of the mountain — only now it yielded raw speed instead of hot sweat. The switchbacks were close and abrupt; seizing the brakes urgently I leaned deep into corners, peaking at 48.4 mph, pumping so much adrenalin that my legs vibrated hard on the pedals.

I had frequent thoughts of frailty on that fifteen-minute ear-popping descent. A frightened piece of my brain kept screaming CAUTION, conjuring terrible images of blowouts, bearing failures, chuckholes, wet pavement, glazed brakes, runaway trucks, and broken steering linkages. But the rest of me grinned insanely and tried to ignore the things that threatened my life on this mad road, this infamous cycling nightmare with grades as steep as twelve percent.

This is bike touring at its best: sweat your ass off by climbing for hours in rugged alpine beauty, and then give it all back in one glorious insane orgasm of speed and ecstasy.

The rain hit the moment I rolled into Lake City, so I ducked under the canopy of a deli and ordered coffee and an egg-a-bagel. In this small town where everybody except the tourists knows everybody else, the atmosphere in the rain is not unlike somebody’s living room.

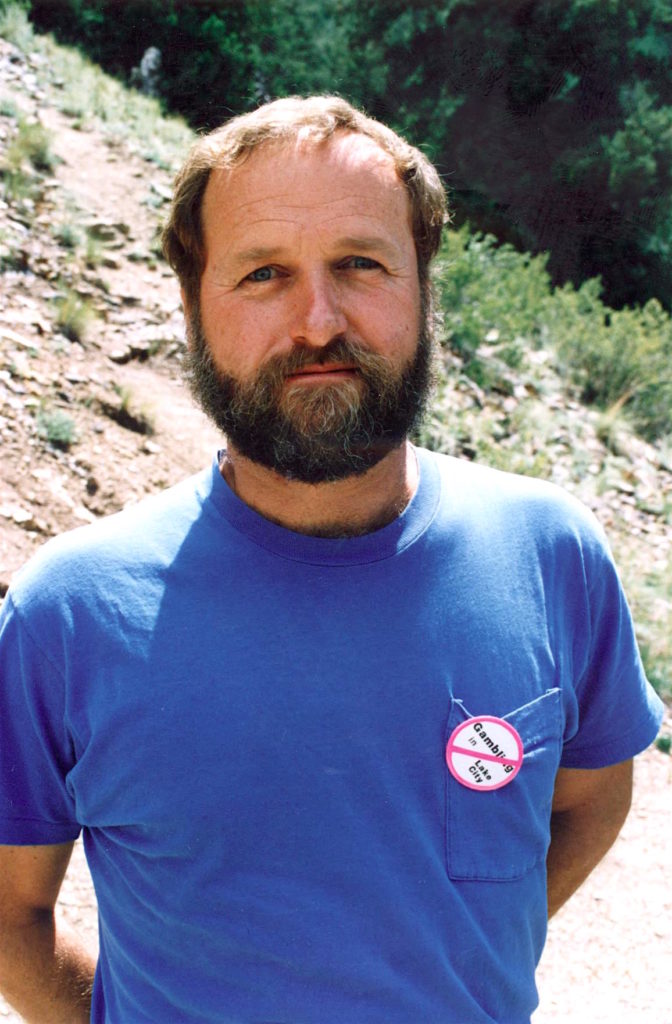

I was looking for Jim Mitchell, an old friend of Frank the Hungarian realtor. Jim had lived in Columbus for years, and I had been hearing about him for as long as I had known Frank. He loomed in my immediate future as a larger-than-life figure, a man brilliant and driven, tragic and complex, a recluse out here in America’s least-populated county. I was almost nervous.

Lake City is an old mining town, a rugged little place once populated by pick-wielding, mule-driving men who endured brutal winters and isolation in their quest for riches. Something of that spirit remains, a frontier echo persisting even though the town is now a quiet summer resort for the refugees of Texas heat. The newspaper is the Silver World, a weekly blend of folksy community issues and historical flashbacks.

This is a place to live in an Airstream away from the mainstream, to go trout fishing, to withdraw from the madness of the real world. It’s a place of Maytag wringers, local color, funky bars, few women, and muddy jeeps.

One such jeep crunched across puddled gravel and parked beside my bike. “Steve?” The deep resonant voice elbowed its way through the gray sounds of the storm and into the deli, followed a moment later by a husky, bearded character stomping off the rain and grinning at me.

“Jim?”

“Hey, you made it! I figured that had to be your machine — we don’t get very many recumbents through here. How much does that thing weigh?”

“About two hundred pounds. Plus me.”

He gave me a hearty handshake. “Welcome! You rode that over Slum, eh? Up here we have a tremendous respect for anyone who carries things up hills. People used to do it with muscles all the time, but now we have petroleum.”

“Petroleum?”

“Sort of a substitute for calories.” His eyes twinkled warmly.

“Ahhh, you drink it!”

“Well, something like that.”

He took me over to his house, a homemade two-story place of idiosyncratic architecture, a juxtaposition of polished and rough-hewn work. Numerous projects were in progress — a kitchen counter, a rear deck, finish carpentry on the stairs. Jim lives alone and works on the house, surviving on memories and old real-estate investments. I sensed a restrained power, a blend of humor and mad intensity, a craggy personality harboring veins of wisdom like the mineralization of the San Juan range around us. It would be an interesting week.

Indeed. A close friendship developed during my stay in Lake City, a town popularized by Peter Jenkins and still trying to live down the gushing exposure. Jim introduced me around, chuckling at my frustrated observation that the few single women are already much sought-after in this social microcosm. That issue shelved, we traveled the jeep trails and explored nearby mountains — and the more time I spent with him the more intrigued I became. How could this generalist of diverse knowledge, this former entrepreneur have become a reclusive mountain man?

It seemed odd, inexplicable. Though I, too, was a refugee of the rat race, I was anything but antisocial. My journey’s highlights have included at least as many blazing relationships as illuminating moments of solitude, and the thought of living alone in an isolated place seemed sad, almost tragic. I probed for the reasons as we puffed along the path to the top of 14,309-foot Uncompahgre Peak.

Ah. It was love. Naturally. It had been an obsession. He saw her as superhuman — a powerful figure in both public and private life. She had been a dynamo in the Ohio legislature, a world-changer, an “elemental force for good,” and she was the only thing that Jim had believed in.

But at the peak of a professional crisis, hounded by Columbus newspapers and pressured by Jim to run for governor, she was broadsided by a truck and killed.

He was wracked with guilt. The little car, the pressure, the whole intense situation — he accepted it all as his fault and grieved not only for her but for those she left behind. He saw himself as Judas, and lost the courage to play the games, to interact and compete. When he discovered that Hinsdale County was the least populated place in the nation, he rid himself of Ohio trappings and moved west to construct a retreat of solitude without dreams.

So this was not at all like the rationalization that has led me to rearrange and relocate homes over the years; this was shattering emotion. I struggled to understand, for I’ve never been that taken. But I saw the broken heart of this powerful man… I heard the tears as we looked down on the Rockies and out at the sky. The beauty around us was almost painful, and with my questions I reminded him not only of the past but also of the fact that opening up again may be impossible.

He wouldn’t survive it a second time.

The vista in all directions was humbling, overwhelming. I had never… never seen such grandeur. Words are useless; even the photographs before me as I write fail to recapture that sense of dizziness and awe. I ran to and fro, oohing and aahing like a little kid, pointing out glaciated valleys and serpentine rivers, handing Jim the binoculars to share my discovery of a tiny far-off tent.

He just smiled and pointed out features here and there, naming the more prominent mountains while quietly enjoying the vastness and slurping fresh Paonia peaches.

The air was thin and cold. The occasional marmot or other beastie ventured close for a bite of GORP. Camp rings of rock testified to the hardy souls who had stayed overnight in this lofty place, and a register sealed in a tube and tucked into a rockpile listed others who had come before us.

I stood and looked down on the million-year history of Rocky Mountain geology, written indelibly in rock. It could have been another planet, another epoch. The few signs of civilization were tentative and insignificant, and I now understood why Jim had come here.

“Imagine the development potential,” I joked. Once, in another life, he had been active in real estate.

“Yeah, just apply to the Bureau of Land Management.”

“Shouldn’t be any trouble — they’re all Watt appointees.”

He pointed to a level area just below the summit. “There’s a good place for the hotel, right down there. Great view.”

“And the restaurant, with Uncompahgre Burgers.”

“Ah,and the ultimate sky slide…”

“Don’t forget the world’s highest golf course — with vertical fairways.” We went on like this, quite scandalizing a father-son climbing team who passed us as we headed down. I grinned at the man and gestured toward Jim, explaining that he was my realtor and that I had just bought the mountain.

But the real thrill of my stay was the day of the mines.

All around Lake City are the echoes of pick-clinking days of yore — high on sheer cliffs of unstable rock appear absurd openings, marked by tailings and remnants of cribbing that streak hundreds of feet down the scree. Mines, mines, everywhere mines: the promise of gold once had thousands of men plying these rugged lands, tunneling into every sparkling crack for the metal that would guarantee their fortune. Many died.

I journeyed with Jim up Henson Creek one day, higher and higher. The air grew cold, the pockets of snow more common. Fields of aspen and pine felled by recent avalanches were a frequent sight, and as we slowly growled up the rough jeep trail he provided a running commentary. “Does anything look strange about that?” he asked, pointing at a scarred hillside to our right.

“Yeah… the trees are all leaning uphill. Was it an ehcnalava?” I had already been working on that one for a few seconds.

“A what?” he asked, startled.

A backwards avalanche.”

“Well, yes, actually. It was an avalanche over here.” He pointed to the left. “It came down with so much force that it bounced and went up that hill, wiping out the trees in the process.”

This was a whole different world. In an Ohio winter, grim though it may be, an occasional branch breaks off.

We moved on, switching to four-wheel drive just before treeline and pressing on toward an abandoned mining community — resorting to our own legs when something more sure-footed than the jeep became necessary.

Panting in the rarefied air, our breath coming in little puffs, we stood and contemplated long-abandoned steam engines, machine tools, and mining equipment that lay rusting in the snow-crushed buildings. Somebody had once dragged individual machine components weighing thousands of pounds up these fierce slopes, and then lived with them year-round. I wondered aloud at this.

“There was money in it,” Jim said.

The power of that motivator became even more awe-inspiring as we began to explore the mines. Tunnels led into solid rock, then branched into a maze as long-ago prospectors chased the mineral veins. We slogged through oxide-scummed water into the heart of a mountain, intent on reaching the face until our sudden confusion and stumbling gait warned us that we were running out of oxygen. It seemed quite humorous, actually, and we flashed our lights around the sparkling icy walls and rusty tracks, growing sillier and weaker by the moment.

“Hey. We better get our asses outta here,” somebody said.

We splashed back to daylight and sat, dizzy, aware that even in this safe and cozy world of the 1980’s, survival can sometimes be a more immediate issue than comfort. I removed from my pocket a little package of glass vials I had found in the mine, and saw that it was a partly used test kit for poisonous gas. We sobered quickly.

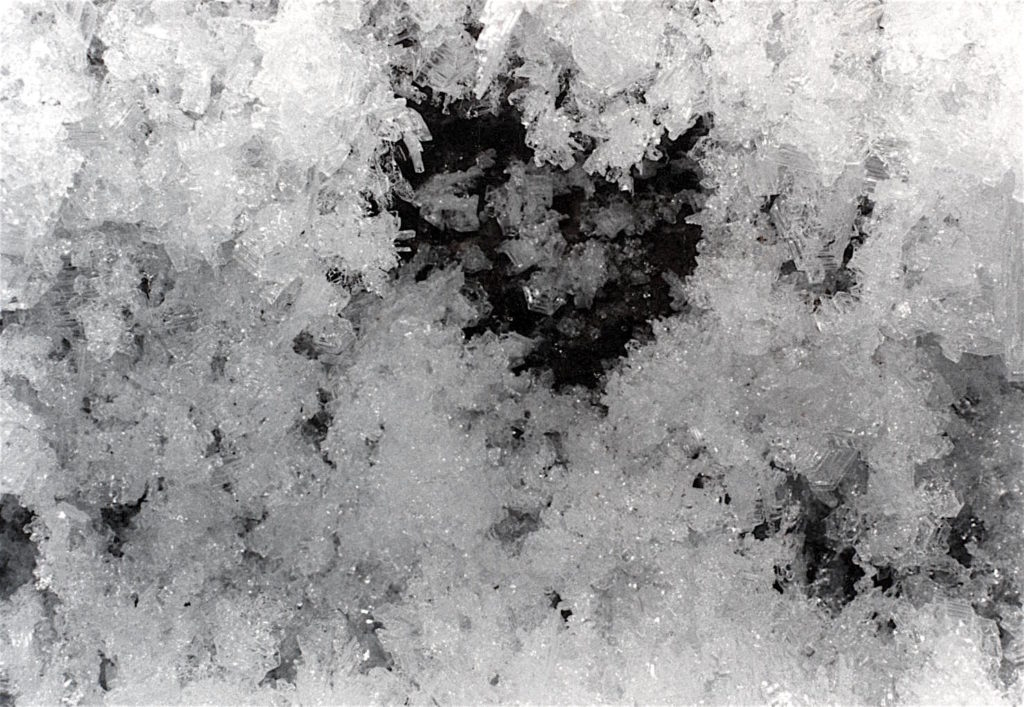

And then we saw it.

High above us, at over 13,000 feet and hidden behind a snowbank, a mine opened into a cliff of quartz. Visible only by its almost-obscured scar of tailings, it set our hearts racing. Why not?

Still breathless, we zigzagged up a vast slope of treacherous scree, sending little landslides rattling down the mountain with our less-than-certain steps. We occasionally stopped to watch them: rocks bouncing so far below that their sound continued long after all visible motion had ceased.

After at least an hour of this, we reached our goal. To the north, Uncompahgre and another “fourteener” peeked through the clouds; below us was the mining camp and the thread of a road that wound down, past the waterfall, past the yellow dot of a jeep, past the treeline, and into the valley. But here was the snowbank, and sure enough, the crushed timbers and violated rock of a long-abandoned mine.

I climbed down into the opening. It was small — almost closed forever by ice three to four feet thick and fallen rocks. But I wriggled through, pushing the flashlight ahead of me on the freezing surface, and found it passable. I was just on the verge of shouting “Come ahead” when I nudged the light and the scene suddenly exploded into thousands of glittering pinpoints: a forest of diamonds, an unexpected universe, a crystalline cave.

Hushed by the magic, I pulled myself further along the ice as I was gently showered by sparkling, tinkling crystals. The reflection of the flashlight was like a Scarlatti harpsichord sonata on LSD — every glint a prelude to a complex and impassioned exploration of light’s possibilities, every shadow a hidden surprise. Perfect glasslike hexagonal crystals three inches across were suspended on complex and impossibly delicate structures; the marriage of order and randomness possessing such beauty that more than once did an awed whimper escape my throat to echo off the long-forgotten walls.

I lay and listened to the chorus of microscopic fractures caused by the heat of my breath, then Jim slid along the ice to marvel in kind. No dirt marred the purity of this place; no humans had passed this way in decades. These meta-snowflakes had grown for years in perennial frozen stillness with no influence but gravity, and the perfection was so complete that we found ourselves embarrassed by the mud we had tracked in, guilt-ridden at the crystals we had swept aside to allow our intrusion into this place of magic.

That such a thing exists, silent, growing with infinite patience; that such a frozen wonder could await my awed discovery in the middle of August — moves me with a sort of humble delight. There lies the essence of the journey: it is not a high-tech quest, a PR gambit, or even that blend of work and play about which I love to rhapsodize. It includes all of that, of course, but it’s mostly a voyage of discovery.

For what else would you call a scene from The Lord of the Rings, materializing as if by magic on a late-summer afternoon in Colorado?

You must be logged in to post a comment.