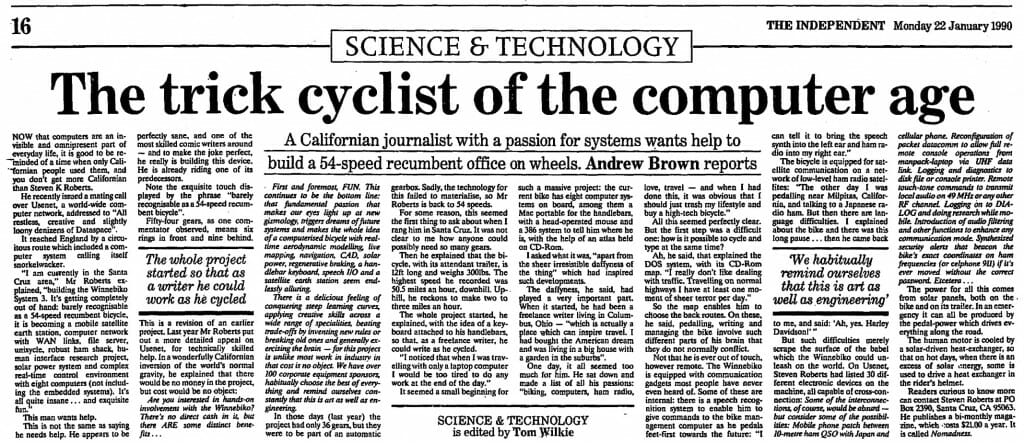

The Trick Cyclist of the Computer Age – Independent

I just love the tone of this… the author doesn’t take me too seriously, and has wonderful fun with the story. It was written while I was in Soquel (near Santa Cruz), working on the bike in a lashed-up combination of workspaces that included a garage and my old school bus…

by Andrew Brown

The Independent (UK)

January 22, 1990

A Californian journalist with a passion for systems wants help to build a 54-speed recumbent office on wheels.

NOW that computers are an invisible and omnipresent part of everyday life, it is good to be reminded of a time when only Californian people used them, and you don’t get more Californian than Steven K Roberts.

He recently issued a mating call over Usenet, a world-wide computer network, addressed to “All restless, creative and slightly loony denizens of Dataspace.”

It reached England by a circuitous route which included a computer system calling itself snorkelwacker.

“I am currently in the Santa Cruz area,” Mr Roberts explained, “building the Winnebiko System 3. It’s getting completely out of hand: barely recognisable as a 54-speed recumbent bicycle, it is becoming a mobile satellite earth station, computer network with WAN links, file server, unixycle, robust ham shack, human interface research project, solar power system and complex real-time control environment with eight computers (not including the embedded systems). It’s all quite insane… and exquisite fun.”

This man wants help.

This is not the same as saying he needs help. He appears to be perfectly sane, and one of the most skilled comic writers around — and to make the joke perfect, he really is building this device. He is already riding one of its predecessors.

Note the exquisite touch displayed by the phrase “barely recognisable as a 54-speed recumbent bicycle”.

Fifty-four gears, as one commentator observed, means six rings in front and nine behind. (Note: actually there were three derailleurs, and in this configuration it had 3x3x6 rings. Later it was increased to a total of 105 speeds, or 5x3x7.)

This is a revision of an earlier project. Last year Mr Roberts put out a more detailed appeal on Usenet, for technically skilled help. In a wonderfully Californian inversion of the world’s normal gravity, he explained that there would be no money in the project, but cost would be no object:

Are you interested in hands-on involvement with the Winnebiko? There’s no direct cash in it, but there ARE some distinct benefits…

First and foremost, FUN. This continues to be the bottom line: that fundamental passion that makes our eyes light up at new gizmology, triggers dreams of future systems and makes the whole idea of a computerised bicycle with real-time aerodynamic modelling, live mapping, navigation, CAD, solar power, regenerative braking, a handlebar keyboard, speech I/O and a satellite earth station seem endlessly alluring.

There is a delicious feeling of conquering steep learning curves, applying creative skills across a wide range of specialities, beating trade-offs by inventing new rules or breaking old ones and generally exercising the brain—for this project is unlike most work in industry in that cost is no object. We have over 100 corporate equipment sponsors, habitually choose the best of everything, and remind ourselves constantly that this is art as well as engineering.

In those days (last year) the project had only 36 gears, but they were to be part of an automatic gearbox. Sadly, the technology for this failed to materialise, so Mr Roberts is back to 54 speeds.

For some reason, this seemed the first thing to ask about when I rang him in Santa Cruz. It was not clear to me how anyone could possibly need so many gears.

Then he explained that the bicycle, with its attendant trailer, is 12ft long and weighs 300 lbs. The highest speed he recorded was 50.5 miles an hour, downhill. Uphill, he reckons to make two to three miles an hour.

The whole project started, he explained, with the idea of a keyboard attached to his handlebars, so that, as a freelance writer, he could write as he cycled. “I noticed that when I was travelling with only a laptop computer I would be too tired to do any work at the end of the day.”

It seemed a small beginning for such a massive project: the current bike has eight computer systems on board, among them a Mac Portable for the handlebars, with a head-operated mouse and a 386 system to tell him where he is, with the help of an atlas held on CD-Rom.

I asked what it was, “apart from the sheer irresistible daffyness of the thing” which had inspired such developments.

The daffyness, he said, had played a very important part. When it started, he had been a freelance writer living in Columbus, Ohio — “which is actually a place which can inspire travel. I had bought the American dream and was living in a big house with a garden in the suburbs.”

One day, it all seemed too much for him. He sat down and made a list of all his passions: “biking, computers, ham radio, love, travel — and when I had done this, it was obvious that I should just trash my lifestyle and buy a high-tech bicycle.”

All this seemed perfectly clear. But the first step was a difficult one: how is it possible to cycle and type at the same time?

Ah, he said, that explained the DOS system, with its CD-Rom map. “I really don’t like dealing with traffic. Travelling on normal highways I have at least one moment of sheer terror per day.”

So the map enables him to choose the back routes. On these, he said, pedalling, writing and managing the bike involve such different parts of his brain that they do not normally conflict.

Not that he is ever out of touch, however remote. The Winnebiko is equipped with communication gadgets most people have never even heard of. Some of these are internal: there is a speech recognition system to enable him to give commands to the bike management computer as he pedals feet-first towards the future: “I can tell it to bring the speech synth into the left ear and ham radio into my right ear.”

The bicycle is equipped for satellite communication on a network of low-level ham radio satellites: “The other day I was pedaling near Milpitas, California, and talking to a Japanese ham. But then there are language difficulties. I explained about the bike and there was this long pause… then he came back to me, and said: ‘Ah, yes. Harley Davidson!'”

But such difficulties merely scrape the surface of the babel which the Winnebiko could unleash on the world. On Usenet, Steven Roberts had listed 30 different electronic devices on the machine, all capable of cross-connection: Some of the interconnections, of course, would be absurd — but consider some of the possibilities: Mobile phone patch between 10-metre ham QSO with Japan and cellular phone. Reconfiguration of packet datacomm to allow full remote console operations from manpack-laptop via UHF data link. Logging and diagnostics to disk file or console primer. Remote touch-tone commands to transmit local audio on 49 MHz or any other RF channel. Logging on to DIALOG and doing research while mobile. Introduction of audio filtering and other functions to enhance any communication mode. Synthesised security alerts that beacon the bike’s exact coordinates on ham frequencies (or celphone 911) if it’s ever moved without the correct password. Etcetera…

The power for all this comes from solar panels, both on the bike and on its trailer. In an emergency it can all be produced by the pedal-power which drives everything along the road.

The human motor is cooled by a solar-driven heat-exchanger, so that on hot days, when there is an excess of solar energy, some is used to drive a heat exchanger in the rider’s helmet.

Readers curious to know more can contact Steven Roberts at <address redacted> Santa Cruz, CA 95063. He publishes a bi-monthly magazine, which costs $21.00 a year. It is called Nomadness.