Winnebiko II Details – California Bicyclist

by Steven K. Roberts

California Bicyclist

April, 1987

High-tech touring… That phrase, if you’re a regular reader of glossy bicycle magazines, probably evokes colorful images of ultralight carbon-fiber frames and aerodynamic derailleurs. High tech means light and sleek, right?

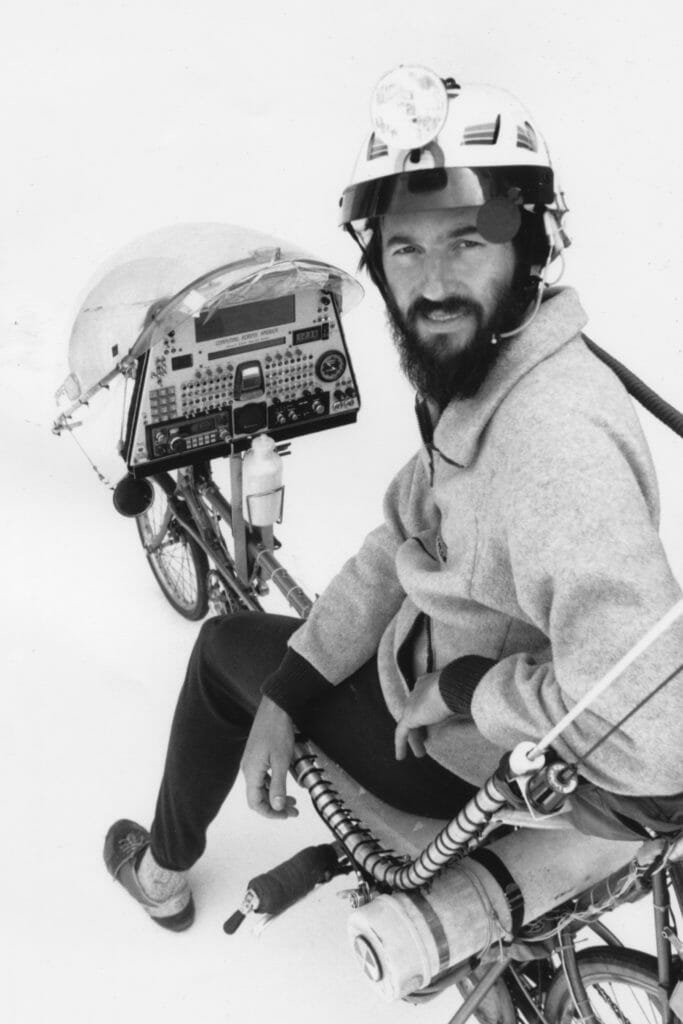

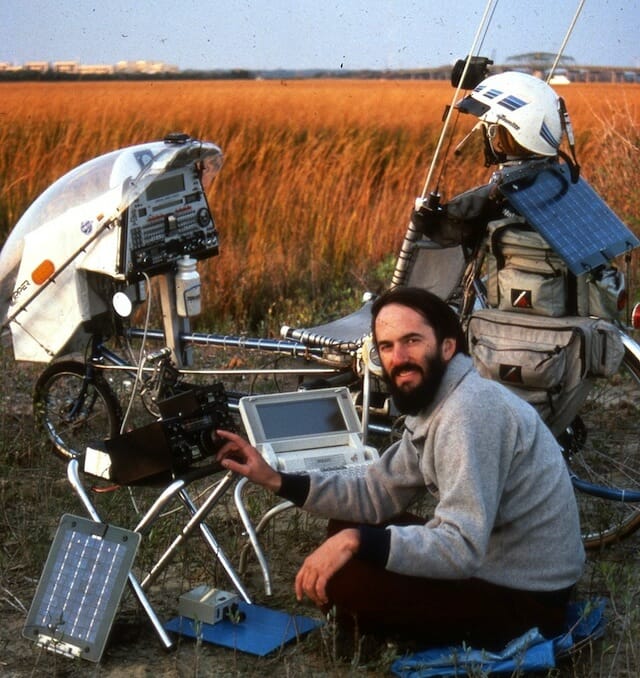

Well, what if I told you that I live full-time on a 220-pound recumbent, and am roughly 12,000 miles into a journey of unknown length? What if I also noted that the bike is equipped with five computers, as well as two solar panels, a ham radio, a handlebar keyboard, and equipment for data communication and speech synthesis? This is high tech of a different flavor— the 1.2 Megabyte Winnebiko II.

I have stopped in Silicon Valley for a two-month system upgrade marathon before heading back into the wilderness and, before I leave “Tech Mecca,” I’d like to introduce you to my machine.

But first I should make a few general comments. Why did I trash a stable suburban Ohio lifestyle and move my freelance writing business to the road? Why do I keep it up year after year, never tiring of the madness, the risks, and the brutal constraints of gravity? Why do I carry 50 pounds of electronic equipment? And… am I just an eccentric, or is there something in this for the rest of the bicycle touring community?

Moving to the Road

In the lingering Ohio winter of 1983, I started the usual turning-30 self-examining: why was I chronically in debt, supporting a boring existence with every dollar I earned? Why was I in Ohio? What did I really want out of life? The answer, once I looked past the list of essential new toys, was obvious: I wanted learning, growth, passion, change, excitement, intelligent friends, sex, publicity, high-tech gizmology, cycling, network access, hot publishing deals, and a sense of FUN to pervade everything I did.

That’s not too much to ask, is it?

My real world, in the context of all that, felt like prison. The solution was self-evident… All I had to do was pack a portable computer onto a recumbent bicycle and travel the country, supporting myself by freelance writing along the way and using computer networks as my “enclave of stability.”

No problem.

A Megabyte Bicycle?

Now you see why all the computers: the Winnebiko is my office, my electronic cottage on wheels. It has been growing more and more elaborate as the years pass, allowing full-scale word-processing through a binary handlebar keyboard and data file transfer via packet radio. I have decoupled from the real world, and move freely through physical space while remaining solidly rooted in data space. Home has become a trio of rather non-traditional places: this radically decked-out bike, America itself, and the thickening global web of information networks that’s accessible through any telephone. (My home system is GEnie — call me “Wordy.”)

All of this is generally intriguing to people, especially techies, cyclists and would-be travelers. But let’s take it beyond that for just a moment and think about the cycling life.

Consider the normal bicycle tour: a week or a month, perhaps more, a finite time bounded by financial constraints. But I’ve seen the tragedy: travelers cutting back on food because the bank account is down to three digits and sinking fast. Their sadness is tangible, for they see the journey ending long before they want it to.

Another effect is the “macho cyclist” syndrome, which is fine on the track but absurd on the road. I meet them too, but we never get to talk very long. They’ve usually set themselves a grueling schedule of hundred-mile days, following a pre-planned route that’s the closest possible approximation to a straight line.

I have no quarrel with racers, of course, nor with those who struggle to achieve their “personal best.” But all too often, what should be a relaxed and therapeutic bicycle tour is handled instead like a corporate acquisition — with all the myriad joys of discovery obscured by deadlines and ruthless objectives.

It doesn’t have to be that way. It took me 3,000 miles to stop treating state lines as trophies … to realize that worrying too much about where you’re going destroys respect for where you are. Had I not been liberated by technology that lets me make a living anywhere, I would never have had time to notice this fundamental truth.

The Winnebiko System

Okay. Here’s the technical content you’ve been waiting for—the anatomy of a high-tech bicycle (NASA style)…

My main computer is the Hewlett-Packard Portable PLUS, an exquisite system with 896K of memory partitioned between system RAM and electronic disk. The high-contrast amber LCD displays 25 lines of 80 characters, and a built-in 1200 baud modem makes the daily electronic mail check-ins easy. But what really sells the machine are the applications software packages baked into ROM: Microsoft WORD, Lotus 1-2-3, dbase II, a “card-manager” filing system, communications software, time manager, and a whole library of utilities. The net effect is a robust bicycle business system that runs on rechargeable batteries and weighs eight pounds — a system that has become so much a part of my daily reality that I’m incapable of imagining nomadic life without it. It rides behind me, nestled in foam along with a 3.5-inch disk drive, sometimes accepting charge current from the bike’s solar panels.

Computer number two, built into the control console, was once a Radio Shack Model 100 — upgraded to 256K and made truly useful through the addition of Traveling Software’s Ultimate ROM. But the machine is hardly recognizable: its keyboard and case are gone, and the display appears on the front panel behind a Lexan window. What happened to the keyboard? It has been replaced by a custom logic system that passes converted handlebar keycodes or software-generated commands. This system is intended for on-the-road text capture (not final editing), and thus connects with the HP via a front-panel connector.

The third system is the “bicycle control processor,” based on a Motorola 68HC11 board. This low-power machine embodies all of the bike’s real-time control and monitoring functions, including handlebar keyboard code conversion, local network control (linking the other systems with each other), electronic compass processing, control of solar battery charging, security system supervision, diagnostics, status display, and so on. Assisted by about 50 IC’s, this processor essentially runs the bicycle.

Computer Number four is a speech synthesizer that speaks any text file transferred to it. The value of this on the bike is threefold: I can have the system read back my own text or incoming messages, and it is a handy way to reduce the volume of identical questions from curious bystanders. “I am the Winnebiko.” it says (either at predefined intervals or under radio control), going on to explain the basics of this strange contraption. The speech board can also respond to a security alert by saying “Please do not touch me!” in a robotically threatening voice.

The fifth system is known as a “terminal node controller.” It’s a Pac-Comm product that handles packet data communication via radio. An unusual breed of computer network has quietly appeared in the last 2-3 years, a sort of digital anarchy of the airwaves, a computer network without corporate sub-strata. Anybody with a ham radio license and a bit of equipment can participate—sending mail cross-country, transferring files, conferencing, and so on. The network is young, but already offers coast-to-coast trunk connections, automatic message forwarding, dozens of linked bulletin board systems, and its own orbiting satellite mailbox. With packet operation possible from the bicycle via the handlebar keyboard and LCD display, I can communicate data from a campground or while pedaling. Ain’t technology wonderful?

The handlebar-keyboard itself is simple: four pushbutton switches are buried in each foam grip, spaced about three-fourths of an inch apart. I type in a binary code: my five strongest fingers, three on the right and two on the left, produce the lower-case alphabet; the right little finger capitalizes. The left little finger is the control key, its neighbor selects numeric and special keys, and those two together cause the others to take on system level meanings such as file operations and major edit functions. In practice, it’s easy — a lot like playing the flute — with each combination accepted by the system when all buttons are released.

So much for bicycle data processing. Now let’s look at the other facilities…

The mobile ham radio station (N4RVE here) is a multimode two-meter rig from Yaesu. In addition to handling data communication, it allows me to stay in regular voice contact with Maggie (my recumbent-borne traveling companion). Bicycle touring without some form of communication is frustrating, as anyone who as ever squinted into the mirror for minutes at a time well knows, “What happened to him? Is he okay back there?” With a boom microphone built into my helmet and a push-to-talk switch on the handlebars, Maggie is never far away (effective bike-to-bike simplex SSB radio range is over two miles). Of course, having two-meter FM capability on the bike also connects me to a huge network of ham radio operators: I store the local repeater frequencies into the radio’s memory as I approach an area, and periodically identify myself as an incoming bicycle mobile. This has led to a number of interesting encounters and places to stay. And — through the repeaters — I can make telephone calls directly from the bike.

A CB radio is also on board, culturally useless by comparison, but still handy enough to justify its weight. I can talk to truckers, hail a passing motorhome for water (this system saved my life in Utah), and chuckle al the residual “good buddy” subculture.

System security is an issue when living on a machine that looks like something from NASA. It’s not that people try to steal it — most are intimidated by the technology — it’s just that some let their curiosity extend to flipping switches and tinkering. To alert me to such behavior, I built in a security system with vibration and motion sensors: when armed by a front-panel key switch, any disturbance causes transmission of a tone-encoded signal that sets off my pocket beeper up to 2-3 miles away.

Other radio-related devices include a digital shortwave receiver, a Sony Watchman micro-TV, and an FM stereo. Naturally, there is also an audio cassette deck, for sometimes it lakes more than a granny gear to climb a mountain…

Mechanical Considerations

Speaking of gearing, the bike is equipped with some unusual mechanical hardware. A custom 36-speed crossover system of three derailleurs provides a 16.9-inch granny gear, a 23-inch “high granny,” and half-step from 33 to 144. With the Zipper fairing and the recumbent’s aerodynamic advantage, I can cruise comfortably at 15-17 mph (assuming a good breakfast and no unfriendly winds). Peak speed so far, flying down a mountain, was 50.1.

Stopping power is critical with my 400-pound gross weight, of course. Moving that much stuff downhill at 50 mph is profoundly exhilarating (on a recumbent, I might note, the entire world, not just the road surface, blurs into an impressionistic confusion of streaked light and color). But stopping is another matter. The Winnebiko II has three brakes: a Phil Wood disc actuated by my left hand and a pair of Mathauser hydraulics controlled by the right. The disc is nice for speed regulation without rim heating effects; the hydraulics will stop anything, dramatically outperforming the various mechanical models I have tried and discarded over the years. To control them with a single lever. I machined a header for the master cylinders, with a sliding cable stop and proportional transfer bar to permit a variable front-back braking force ratio.

The frame itself was custom made by Franklin Frames of Columbus, Ohio — after I did enough brazing in my basement to convince myself that frame building is an art form. The geometry is entirely custom, suited to my giraffe body and the special requirements of all the on-board hardware.

Power for the electronic systems is derived from a pair of Solarex photovoltaic panels, producing 10 watts each in full sun (roughly 1.3 amps total into the pair of four amp-hour batteries). These new SX-Lite units lack the traditional glass and aluminum frame, and are each 12.5 x 17 inches. Since they can pump enough current into the Ni-Cads to overcharge them, I have built in extensive power monitoring and control circuitry: A digital panel meter with a thumbwheel switch can show instantaneous current into or out of each battery (as well as any system voltage), and the BCP can throttle back the charging process if its calculations indicate that the batteries are full.

Other voltages besides the two 12-volt battery buses are needed throughout the system, and this is one of those areas that can cause significant overhead if attention isn’t paid to losses. There is a small aluminum box containing switching supplies that coolly provides 3, 5, 6, 9, and -12 volts (all available on the front panel for external accessories). Considering the special requirements of a bicycle system, the extra design effort here has paid off well: when the two processors required for text editing are active, total system current drain is only 130 milliamps. A sixth power supply, unrelated to the others, is mounted up front with a coiled cord to allow battery charging if I have gone too long without sunshine.

Instrumentation on the front panel is largely geared to the major electronic systems already described, but there is also the obligatory Cat-Eye Solar to display speed, distance, cadence and so on. This elicits interesting comments from fellow bikies, who stare al the machine in awe then suddenly recognize something familiar. In addition, there is an altimeter (useful on mountains, and also helpful in predicting weather conditions), an Etak electronic compass, time/temperature display, and assorted system status indicators.

Mechanically, the electronics package is designed to separate from the bike with a minimum of effort. I open three toggle clamps, unplug six connectors, and take it into the tent at night, yielding a “tent control system” just as useful as the mobile variety. The 45-pound unit handles heavy downpours with no problem — with the fairing and Velcro-on waterproof covers, it has withstood all-day rides that quite saturated my Gore-Tex. So far, the system has suffered shock and vibration without incident, unfolding easily for service but surviving heavy abuse on the road.

Safely factors are always a major concern when you habitually press your luck by living full-time alongside logging trucks, drunks, motorhomes and the routine madness of the highway. I have become a firm believer in helmets, reflectors, orange flags and good lights. Bicycle Lighting Systems offers a line of industrial-grade products that quite outshine the typical bike lights. I went with a seven-inch yellow barricade flasher that makes me look like a roving hole in the road, a two-inch red taillight, and a four-inch sealed-beam headlight.

In addition, I have recently added a Cycle-Ops halogen helmet light, which has the delightful characteristic of putting light where I’m looking, not just where the bike happens to be pointing. (Admit it, you too have zigzagged drunkenly through neighborhoods at night, trying to highlight street and house number signs.)

Finally, the machine is equipped with all the usual bicycle touring gear: stove, food, clothing, tools, candles, medical supplies, microfiche documentation library, flute, binoculars, camera, maps, digital test equipment, spare inner tubes, frisbee, coffee maker, office supplies, butane soldering iron, and so on. My tent is a vast “Peak Pod Four” from Peak One, very much in the porta-condo class at 108 square feet under cover. Other outdoor gear — North Face down bags, Gore-Tex rain suit, Patagonia bunting, polypro underwear, and so on—is undergoing constant revision as fabric technologies continue to improve.

There… a marathon overview of the Winnebiko II. If any of this seems insane, think about gravity and how long I would continue to drag around something that isn’t practical (and, preferably, multifunctional). This is a wild blend of serious business and fun — a case of personal computers and technology carried to an exquisitely mad extreme.

If there’s any message at all for fellow cyclists, it would be along the lines of fashion. Right. This affair never would have survived the confusion of startup if I had followed prevailing cycling fashions. Ultra-light weight, lycra tights, skittish frame geometries, aerodynamic spoke nipples… all have their place on the racing circuit. But if you’re out there exploring the world on your trusty machine, make it an appropriate one, matched to all your needs. You — and it — will last longer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.