Imperiled on a Lee Shore

As in life, disaster at sea sneaks up fast. Conditions deteriorate in a downward spiral, quietly closing off options while you fiddle with trivialities, driving you inexorably toward a dead end long before you realize it. At some point, the vague dread you’ve been feeling all day snaps into sharp focus; it’s no longer a colorful NOAA movie of well-fletched wind arrows against a colorized map of gales in the Strait… it’s here and now. Buoys that were way over there are suddenly right here; forget lunch, start the engine, turn on the windlass breaker, throw me the leather gloves, we gotta get out of here or we’re gonna lose the boat!

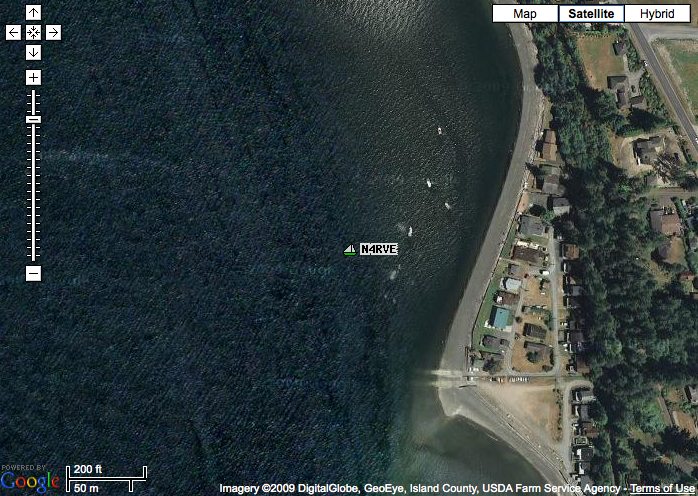

It wasn’t supposed to happen that way, of course. I had known for two days that Saturday was going to be feisty, and fully intended to get off our completely exposed “anchorage” against the lee shore of Camano Island long before it became an issue…

I had no illusions about any protection here, but it was close to the lab and handy logistically for the week that us cruising riff-raff had to vacate the marina to make room for go-fast toys in town for their annual regatta. It had been a mostly-calm stay but for an early lightning storm and a few gusty late-afternoon Force 4 northerlies that were only mildly alarming.

But there were unexpected complexities. Off the coddling of shore power for the first time in a while, my 8-year-old battery bank revealed the quiet disaster that resulted from the Prosine forgetting during a crash that they were AGM, charging them for months as generic gels. They were nearing end-of-life anyway, but this sped the decline, necessitating a somewhat ridiculous transfer of 560 pounds of new Group 31 Fullrivers off the beach via dinghy, followed by the same load in the opposite direction to shed the old ones. That was Friday, and I was playfully making jokes about A Salt and Battery while flexing long-dormant arm muscles, monitoring current flows, and planning the installation of the new Outback inverter/charger that has been patiently waiting in a box since fall.

Up next was a sailing weekend with friends, including an overnight of crabbing and dining in a protected anchorage, but watching the unfolding weather predictions I knew we were in for a blow. We had to get off the lee shore anyway, so might as well make an adventure of it, yah? If conditions get sloppy, we’ll just duck around to the other side of the island, drop the hook, and play there until the system passes.

All this carried a sort of energizing buzz of anticipation, but shoreside events conspired to delay departure into the danger zone. The lab security system was triggered by a spider having dinner in front of a PIR sensor at 1:30 AM, leading to a flurry of activity including a police visit, and twelve hours later, still trying to get out the door, a puddle that I initially attributed to the canine child-surrogate turned out to be the hallmark of an iced-up freezer that needed immediate defrosting (food was already mushy). More lost time, more hassles… and more rising wind.

We finally made it to the beach and undertook three back-to-back dinghy shuttles. I was knocked flat by a wave that dumped the boat on top of me, Bonnie got a leg caught and barely avoided getting slammed, Sky had a close call with a seawall, and Suzanne did quite well after being the first to brave the paint-chipping transfer to the stern of Nomadness, still stately compared to the dancing boatlets all around but starting to pitch in the building seas. While our guests worked to stow gear and food, Sky and I wrestled with the dinghy hoist, finally getting things tidy enough for what was obviously going to be a pounding.

That’s when I noticed that we were dragging anchor on 120 feet of chain, drifting into a bevy of little motorboats, the beach dangerously close astern. Red alert!

The Battle

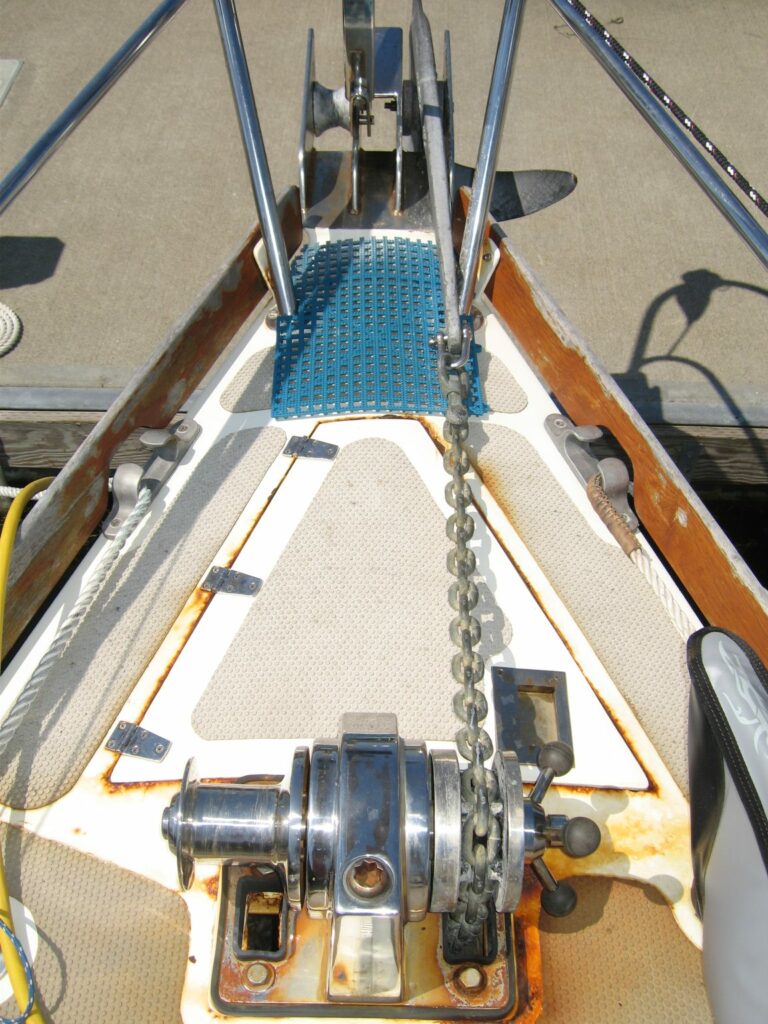

I fired up the diesel, grabbed the headsets, threw one to Sky, donned leather gloves, and made my way to the pitching bow. “No time to change, screw the dog, we’re going now. Keep the bow pointed into the wind!” It began as it usually does; she got the boat creeping forward as I started to bring in chain. But something quickly went wrong… the bow was blown off to starboard, and we came up tight on the still-fast anchor. Coupled with the violent vertical motion, the force of this was enough to yank the chain free. The slipping windlass clutch was no match for the momentum of a running chain, and within seconds all 300 feet of it had flown off the bow roller while I yelped and tried (pointlessly) to slow it down by hand.

I’ve never even seen the bitter end of my anchor rode, and had no idea whether it would disappear completely – something normally considered a disaster. In this case, that would have actually been OK, since we could have sent a diver after it the next day and avoided being pinned to a lee shore. The more likely possibility is that the end would be bent to a length of line that is in turn made fast to an eye in the anchor locker, allowing the ground tackle to be cut away in an emergency.

But it was neither. I didn’t have time to examine it closely, but there was a big knot of chain, apparently seized or clamped; this slammed into the bottom end of the hawse pipe with a loud bang, and held.

Well, hell, now what? A quick glance to leeward revealed that we were between other boats and falling fast toward the rocks, and the only way out would be to recover 300 feet of all-chain rode and a 65-pound Bruce anchor with a failing Lighthouse 1501 windlass clutch and intermittent deck switch. Any attempt to haul the chain while 18 tons of boat strained against it was futile, so we had to work to windward to make slack, gain ground during the few seconds available, then hold it with the hook of a cleated snubber to keep from losing it again. This would have been impossible alone, and nearly so without the full-duplex hands-free communication afforded by our headsets (they’re not industrial quality, and are prone to noise and interference, but they saved our asses on this day… $60 well-spent).

I can only describe the process as brutal, hard on equipment and bodies. I tried to keep Sky advised of the angle that the chain was running into the water, but it was all she could do to buy us a few precious moments of nose to wind… and that frequently involved going around and coming up hard. At one point, I saw us starting to encircle a mooring buoy, which would have complicated things considerably by fouling our chain with theirs, and shouted orders to hit reverse and do a 3-point turn. Bit by bit, I hauled in slack and manually attached the hook to keep from losing precious links.

We must have created quite a show for the vacationing folks in their beach houses, cooking crab and drinking beer, especially since Sky had thrown on a temporary miniskirt to get out of wet clothes from the dinghy mishaps. We’re canvassing the neighborhood to see if there are any photos; if anyone stopped gawking long enough to grab a camera, I’ll post them here (unless they’re NSFW!).

Escape

After a 30-45 minutes of this ordeal, soaked by waves over the plunging bow and nearing exhaustion, the painted marks on the chain indicated 5 fathoms… meaning that we had broken free. Sky drove us to windward to get us off the deadly beach, slowing only when I got the anchor to waterline to keep it from flailing wildly. Once stowed, we powered up and headed for the lee of Whidbey Island, the anemometer clocking 30-35 including our own speed.

But now what? According to NOAA, this wind was going to be with us for a while, and there were no protected anchorages nearby (besides, at this point I was wary of anchoring; the windlass needs to be rebuilt). Cornet Bay, a cozy little nook at the east end of Deception Pass, was 3 hours away and likely packed with weekendeers seeking refuge… an assumption that was later proven correct when I had a chat with a friend who witnessed the gusty anchoring frenzy there. La Conner would be about the same distance and seemed alluring, but wind howls over Skagit Flats and the narrow channel is unforgiving… one error and we’d be aground on a falling 12-foot tide. I grabbed the VHF and called Oak Harbor Marina.

“I don’t recommend it,” the fellow said. “We have 30 knots over the seawall and the anchorage is all whitecaps.”

But after much discussion, I made the executive decision to go for it anyway: it’s familiar territory, help would be available, the anchorage would be a backup if docking failed, and if even that failed we could fire up the nav software and tiptoe out of the channel to motor around in the dark until things calmed down a bit. Set course for Red Buoy #2!

The Second Battle

Nomadness is a stout ship, and before she came into my life covered both coasts of North America, with a couple of Panama Canal transits and lots of time in the Caribbean. So I rather trust her, and the crossing of Penn Cove, where the gale in the Strait was only slightly attenuated by the narrow neck of Whidbey Island, was actually exhilarating. I drizzled a little hydraulic steering oil into the bouncing pedestal with a makeshift funnel, since the wheel felt bubbly after all the excitement, but otherwise all was well and the new battery bank was happily slurping up alternator amps.

The oil led to an amusing moment, however. I was peering around with the binoculars, trying to find the outlying buoy so I could keep it safely to starboard, when Sky called from the companionway: “Could you hand me the hydraulic fluid? Zuby really likes it.”

“No! I need it for the steering system!” It took me a moment to see why they were all laughing at me…

But we had a job to do. Alternating between VHF and cellphone, I contacted Mack the harbormaster, Jerry of the transient Mirador, and Frank of the resident Blue Moorea… making sure that we would have the best possible chance of getting our lines caught before the wind started having its way with my sometimes recalcitrant vessel (she does not behave well without steerageway, making close-in maneuvers much too exciting in wind and current). This was about twice the wind speed I had ever had for a docking attempt… and the force rises with the cube of velocity. Doubling the wind speed means 8 times the force on hull, rigging, kayaks, and everything else that would conspire to blow us off.

The approach was dicey. Three boats in the whitewater anchorage bucked and strained at their chains, and I was being directed to the unfamiliar north entrance that included a skinny sidewind romp along the seawall with a hard U-turn at the end. I swung wide, lined ‘er up, and was a little relieved to see the wind only a few degrees off the nose. OK, here we go…

Three women stood by to toss lines aboard the closing Nomadness; five men on the dock prepared to catch them. I nosed in and a bow line made it, but I timidly dropped power too soon and started to blow back at an alarming angle while the guys fought to hold us. More lines, bursts of power, fast cleating, straining muscles… and at last we were made fast.

The dock angels drifted into the night after shrugging off our hearty thanks, and almost immediately I got to repay a bit of docking karma with the next white-knuckled guy. Later that night, one of the boats in the anchorage dragged down on the seawall and some brave soul leapt aboard, deployed fenders, and lashed her to a pole to keep her off the bricks. This is the best thing about the nautical community.

It was surreal, after all that, to be cracking fresh dungeness crab, enjoying salad from our garden, and drinking much-needed wine with Sky, Suzanne, and Bonnie. Wind whistling around, warm feminine chatter, laptop aglow, instruments still on to attach numbers to the howling outside… all quite cozy aboard our little ship after a vigorous day that already seemed dreamlike and impossible.

I love your blog and read it religiously. However it would be great if you would explain some of the terms that you use, especially when you use acronyms. I hate having to stop and look up an acronym in order to understand your posts.

Thanks for the kind words, and the reminder… I'll use the acronym HTML tag more often (it's the one that pops up a definition when you roll over the term). Cheers!

[…] Describe the most challenging situation you’ve experienced on your boat and how it performed. In a URL: http://nomadness.com/blog/2009/07/imperiled-on-a-lee-shore.html […]