An Awesome Voyage

Computing Across America, Chapter 21

by Steven K. Roberts

Gulf of Mexico

January 22, 1984

If a man must be obsessed by something, I suppose a boat is as good as anything, perhaps a bit better than most.

— E. B. White

I wandered the docks of Fort Zachary Taylor with a yellow plastic band affixed to my wrist — one of those crimp-on ID bracelets they hang on newborns and corpses. In a sense, this was a rite of passage as well: I had tired of my decadent tropical interlude and now looked out to sea. It was time to move on.

But acquiring that little yellow bracelet had not been easy. It was a closed party there on the sun-drenched docks: A yacht race was inbound from Fort Lauderdale and they couldn’t have the teeming masses getting in everybody’s way. To pass through the gates of this old Navy base for the occasion, you had to have both money and connections — a tricky combination for a broke nomad.

The connections were easy enough. Ken Burgess, who had let me stay on his boat for a couple of days, not only hobnobbed in the local yachting culture but also carried a military ID. But the other problem was a little harder: Even though the price of admission was embarrassingly low — like $15 — I didn’t have it.

It was time to hustle some cash.

In a tourist-oriented place like Key West, anything out of the ordinary can be elevated to street theater. I had occasionally joked about cruising Sunset, passing the helmet for donations — so what the hell. Desperate times, desperate measures. I pedaled over to Mallory Square and began the show-n-tell, my helmet upside-down on the seat and primed with a dollar bill.

Within minutes, I had an audience. In a stage voice, I spoke of Sara Lee pastries, high winds, and lowlife guitar-swingers; I held high the computer while rhapsodizing theatrically about the Miracles of Modern Technology. I told a Miami lawyer what kind of computer to buy, turned a Houston engineer on to CompuServe, and put a wide-eyed Boston cyclist in touch with Jack the framebuilder.

Then I pedaled away in the dark with $34.80 in my pocket, wondering why I hadn’t thought of this a week earlier.

So there I was, a wealthy man at last, standing beside my freshly polished bike on the dock. I waited for the influx of fellow yachties, knowing that before sunset I would have water passage to somewhere.

The first ship in, by a comfortable margin, was Thursday’s Child — a sleek 60-footer designed for the staggering feat of singlehanded transatlantic racing (she later broke Flying Cloud’s New York to San Francisco record around Cape Horn by 8 days in 1989). Her decks were covered with solar panels, and all control lines terminated in a maze of winches and cleats at the helm. I gaped. As fellow users of photovoltaics, wouldn’t the owners of this half-million dollar beauty invite me aboard for a ride?

They didn’t, but the afternoon was yet young. The docks grew crowded as boats poured in amid scattered cheers. Rafted three deep along the walls, they bobbed gently in the harbor: Motivation, Sinbad, Go For It, Puff — all told, some $25 million worth of wind-powered hardware. Crews scurried about in tired jubilation, stowing sails, coiling lines, and hoisting high their beers in the eternal camaraderie of the sea. No… it wouldn’t take long.

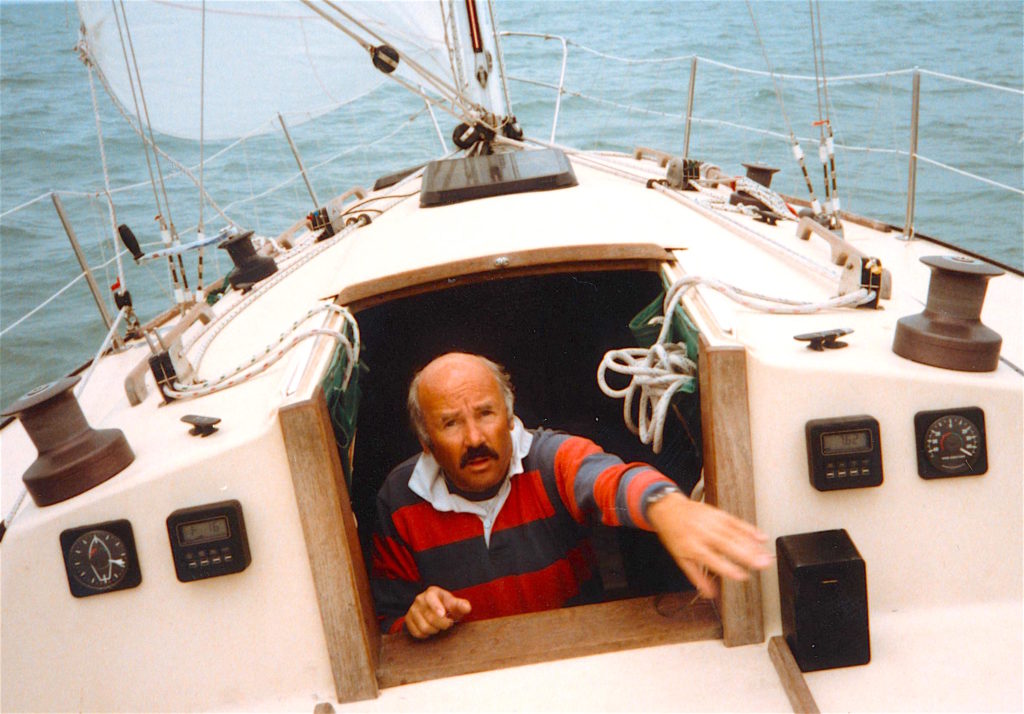

I kept up a banter with the circle of bike-admirers and soon met Bob Horst — bald on top, silver on the sides, dark-moustached in front. He eyed the Computing Across America logo emblazoned across my fairing in patriotic colors, and with a twinkle in his eye began asking well-informed questions.

He mentioned that he owned not only an Apple Lisa and a Minneapolis computer store, but also a J36 racing yacht known as Awesome! As soon as I spoke of my quest, he offered a lift to his home port of Clearwater. But where to stow the bike? We popped open a couple of beers and talked it over.

“How about here?” I asked, pointing at a long open area along the railing near the well-instrumented helm. It looked easy enough to me.

He squinted at me critically. “You ever sailed before?”

“Well, Hobies…”

“You don’t want anything in the way back here.” He gestured to the winches. “It can get pretty busy.”

“OK, how ’bout up there on the foredeck?”

“Two problems. Your bike will get drenched in saltwater, and it’ll get in the way of the jib. No, I think the stern’s our only hope.”

I looked, aghast, at the stern. The only way my eight-foot bike was going to fit there was on the outside of the rail, lashed to the ladder. My heart sank — which is exactly what I figured the bike would do the moment the first big wave came along. Filled with misgivings, I finished my beer and pedaled off in search of plastic sheeting, packing tape, and WD-40. And Dramamine — just in case.

I showed up at the dock the next morning, already imagining the professional diving operation that would be required to rescue my barnacle-encrusted Winnebiko from the murk of the Gulf floor. My job was to soak the machine down with WD-40 to protect the metal from salt water, then wrap the whole thing in polyethylene and tape securely. We would then tie the package on the back of the boat and hope it wouldn’t fall off. The harbor was peaceful, but NOAA weather radio spoke of 8-12 foot seas and 20-30 knot winds out in the open Gulf.

But after reconsidering the problem, we discovered that the bike might fit — just barely — in the forward cabin. We removed the wheels, flagpoles, and map case, then squeezed it down the hatch. With considerable juggling and teak-scratching we wrestled it through the galley and past the head, stuffing it at last into the starboard sail compartment. Much better. The bike would have to withstand two days of violent pounding, so I tucked my gear around it, padded it with everything from sail bags to towels, and lashed it down.

And we were off — motoring out of the Key West harbor, avoiding the brown water of shallow shoals while hoisting the canvas. The storm jib was used in anticipation of heavy weather, and I set to work on the tasks assigned: this wasn’t to be a free ride.

“What kinda knot you want in here?” I hollered above the wind as I straddled the open hatch and wrestled with the job of tying up the mainsail at its second reef point.

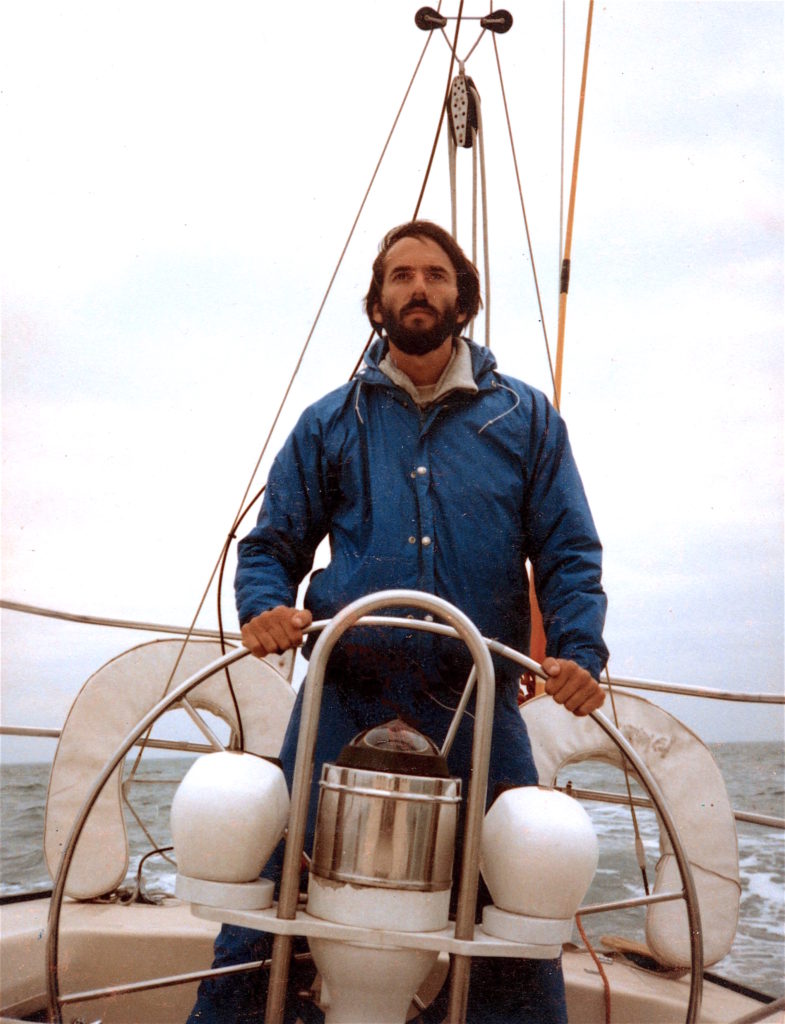

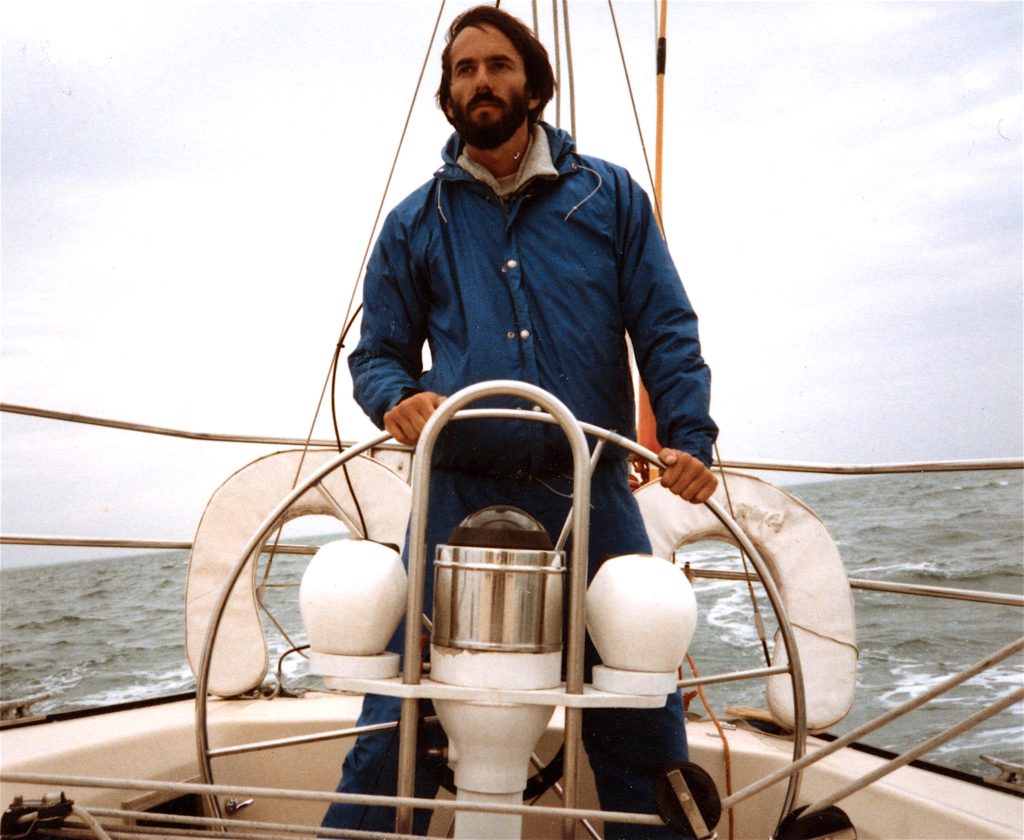

“Put any kind of knot in there you want. Put in the kind you wanna take out at 3 a.m., ’cause when I can’t get it out, I’m gonna call ya!” The speaker was Mike, a rugged Tom Selleck sort with a quick grin, turtleneck sweater, and yellow boots. In the pecking order that was established, he was number two, followed by his wife Marcia, sandy-haired collegiate Dave, and finally me. Their objective was to quickly train me so they could get a decent night’s sleep after three days of racing and partying.

I had to ask how to do everything — turn on a light, tie a knot, use the head. That last item turned out to be more of a challenge than I would have imagined, for as the sea grew rougher it became nigh impossible to remain standing anywhere in the bow. Imagine: crouched in a tiny room with knees, ass, head, and arms braced hard against the walls, one hand trying desperately to aim at a little stainless-steel bowl while everything moves, including my dizzy perceptions. And just when I decide to cut loose, a big wave hits and the whole affair flies ten feet skyward, hovers for a sickening moment, then drops with a mighty <CRACK>. In the sudden need to avoid serious personal injury, some things have to take a back seat.

Perhaps that’s why there’s a floor drain in there.

I was trained on the helm while it was still light (and while we were still in the relative calm of the channel). “Hey, this is a piece of cake,” I remember thinking. “Don’t know why all the fuss about storm jibs and reef points…” I took a salty sip of beer, blinked away the beginnings of mild queasiness, and surreptitiously ate a Dramamine. Just in case.

The helmsman’s job is simple: hold the course. There was a big compass right in front of the wheel, and without any visual reference points on the horizon all I had to do was keep the needle pointed at 345°. No problem — but for the fact that a thirty-six-foot sailboat doesn’t respond instantaneously to rudder movement. My first watch was an erratic sine wave of wild overcompensations, a large wet version of that ride, long ago and far away, on Robby McCormick’s strange low-slung bicycle.

“This is a little easier than riding the bike, eh?” called Bob, as a colorless dusk descended like a heavy pall of smoke.

I raised my thumb.

“I don’t know,” said Mike. “I think we oughta get him up there on the foredeck with his bike, pedalin’ away. Give us some more power.”

I chuckled at the thought. “Maybe with a big propeller I could keep this baby moving on windless days.” It was hard to imagine a lack of wind — spray was breaking over the bow and covering us with a sheen of seawater. The triangle of white canvas snapped hard, pulling us into open water at six to seven knots. I looked around and saw only water, sky, and the occasional color-coded styrofoam marker of a lobster pot bobbing in the swells.

“You better get some sleep,” Bob told me, taking the wheel. “And get your foul-weather gear together — you’re on at 3 o’clock and it’s gonna be cold.”

I crawled below and rooted queasily about, trying to find all the Gore-tex and polypropylene clothing that I had tucked around my bike. I lurched and spun, the experience of moving about in the tiny hold a crazy one of disorienting sensations. I fought for control over my confused vestibular system and laughed out loud down in the violently pitching bow.

Back in the pilot berth, my bundle of clothing ready for the graveyard shift, I stretched out on a narrow bunk and tried to relax. The thought of actually sleeping under these conditions seemed absurd: sounds of gurgling and splashing surrounded me; the metallic crunch of sail-winching just over my head startled me; the creaks of stressed materials raised questions about the structural integrity of the ship. Sleep?

But it didn’t take long. Somewhere in a dream squawked a marine weather forecast — the businesslike voice I had been hearing for decades on my shortwave radio now laden with personal significance. Those weren’t just numbers anymore, I thought, as I lay there listening to the guy talk about squall lines. I dozed again, dreaming of adding LORAN-C to my bicycle and schooning across the prairies under a great blue spinnaker. It seemed only moments later that a hand shook my leg.

“Steve? You’re on. Hold course at 345, and if it gets bad, just let out the main a bit. Kill the autohelm as soon as you get up there — it sucks down the battery — and holler for Marcia at five. And use the safety harness!”

“OK,” I said with simulated confidence. “Good night.”

I dressed and emerged into the chill, snapping my harness to the high starboard railing. This safety measure no longer seemed superfluous, for the craft leaned dramatically to port, driven by a gusty sidewind of twenty to twenty-five knots. I stood with one foot on the slippery rail only inches above rushing froth. My hands, numbing already, gripped the wheel; my eyes flicked over the instruments in semi-comprehension. For a while I struggled to hold the course, but then I began to relax, flowing with the motion of the boat. Before long I forgot my fear that the whole mess would tip over and dump us sputtering and gasping into the cold water, and soon the violent sea started to feel natural… then exhilarating… then alive and part of me like a billion windblown gallons of pure high-octane adrenaline.

I felt the rhythm of the elements and learned to move with them in unconscious synchrony — free of the need to concentrate on wheel and compass, I grew enchanted by the scene. With every lurch, water broke around me in a phosphorescent spray, illuminated by the red and green lights of the bow. The white light of the stern set our turbulent wake aglow, and on the crest of a swell I could occasionally see the lonesome lights of a shrimper plying the waters far off to port. Overhead was the mainsail, a five-story sculpture of fabric glowing pale in the moonlight and propelling us across the water like a silent ghostly engine.

The moon was three days past full, and it played tag with those bright, swift clouds that always seem to make people shiver and mumble something about Sleepy Hollow. And stars — lots of stars. The sky was bright and dramatic, and I flashed the universe a “thumbs-up.”

Suddenly a wraithlike bird — or something — zipped overhead so fast that it was gone before I could finish raising my head. Staring up, I caught a meteor in the act. I looked back down to the instruments, which glowed orange in the night while reporting the observations of ever-vigilant computers and sensors. Everything, on and off the boat, was alive and changing — a secure feeling of high-tech here in the wild, ancient element of the sea.

Salt in my beard. Cold wind, numb hands, halyards snapping. Endless sea, endless sky. There was a sweet loneliness about it, the occasional light of that distant shrimper only intensifying the sensation of being on our own and exquisitely removed from civilization. Of course, we were hardly out of touch: one flick of the switch on the EPIRB and we would look like a five-alarm fire as far as the Coast Guard was concerned. But still… we were alone. I savored the notion, standing proudly at the wheel and scanning the distant horizon as if watching for the shores of a New World.

Then my watch ended.

And ended.

I tried to call out above the roar of the elements, but despite a full bladder and serious weariness I was loathe to turn over the helm to Marcia. It was a night of perfection, a dramatic transition between the languor of the islands and the madness of the highway. I stopped my hollering and stayed on till sunrise.

The day began as a vaguely discernible light in the eastern sky, growing paler and paler until the heavens and reflecting waters were a single vast palette of glowing pastels. Charcoal clouds scudded through pinks and yellows, backlit gloriously until the sun suddenly popped into the scene to render sharp shadows where a moment before had been only softness. Venus, which had sparkled like a well-lit diamond, winked out abruptly.

Then I heard the unfamiliar luffing of the sail, took a quick look at the compass, and realized that I had stopped paying attention and was now wandering all over the Gulf of Mexico. I made an abrupt 60° course correction just as Marcia emerged from the hatch to take my place. Oops — er, good morning.

It was a day of bright sun and lazy conversation. Our steady tack brought us within twenty miles of the Florida coast, where the water was considerably calmer. By evening, conditions were so stable that even the hundredths digit of our speed seldom changed: the liquid-crystal display was frozen at 7.52 knots.

I went easy on the beer, washing down another Dramamine (just in case). We sat on the deck, idly swapping stories: Bob and I were both survivors of the personal computer’s turbulent infancy and had even done battle with some of the same horrid old products. Schedules were forgotten in casual watch-swapping, and before long the speculations began: “Hey, isn’t that Venice over there?”

“Nah, we’d be able to see the hotel.”

“I don’t know — it sure ain’t Sarasota.”

“Well, hell, go check the LORAN.”

Nightfall again, Florida lights clearly visible. There was pleasure in looking at what I once would have seen as random twinklings on the water and recognizing them as channel markers. We slipped past a lonesome moaning buoy outside Tampa Bay, flashing once every 2.5 seconds. Far up the coast lightning split the sky — but nearby were glittering city lights and buoys blinking in the balmy air. Our voyage was about to end, and I sat with my flute on the foredeck playing sad sweet music of wistfulness and change.

Then the universe saw fit to kick in a musical contribution of its own just as we passed the next channel marker — this one a softly clanging bell. I had stopped playing, and someone switched on the radio just in time to hear “Sailing” by Christopher Cross.

I turned on my microcassette recorder and caught the song in a background of water and buoy, wind and sail. This was entirely consistent with the flavor of my journey. There’s no way to hurry on a bicycle, and there’s sure no way to hurry on a sailboat. That van ride to Fort Meyers would have been cheating, but this wasn’t even slightly out of context — just a fitting conclusion to my stay in paradise.

We motored into the dark Clearwater Harbor at midnight, blasting the air horn long-short to wake the bridge-keeper. The piercing sound echoed from hotels and condos, and when we proceeded through the lights and sights of a city sleeping I could smell the road. I could almost see it out there — stretching before me to infinity.

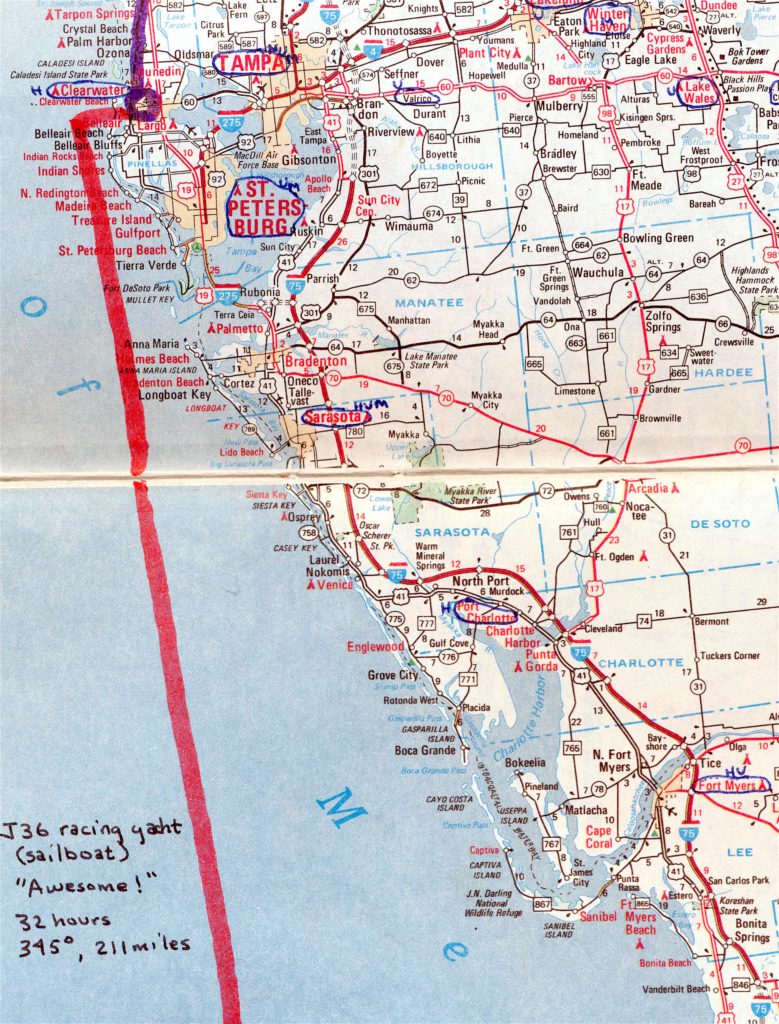

“345°, 211 miles, 32 hours,” Mike observed.

“Right on target,” Bob answered.

“Dead on.”

I now understood the nautical addiction. I helped clean up and stow the sails, then crawled below to sleep alone on the Awesome! I thought about my bio-granddad and his epic voyage, three-quarters of a century ago, through the same waters. Civilizations and technologies might come and go, but the sea will remain…

I lay amid the restful lappings of tame harbor water and looked ahead to the road… but a nautical seed was planted.

Personal Note: This nautical interlude had long-term effects, with the imagery of that night watch following me over the next quarter century. After the bike epoch ended, I shifted my attention to water with the Microship project… but that was still on a human-power scale with an amphibian pedal/solar/sail micro-trimaran. In 2006, I tried a “Microship on Steriods” in the form of a Corsair 36 trimaran, but less than two years later I bought a big monohull and named her Nomadness. The 32-hour adventure described in this chapter had a lot to do with that, and is a reminder of how powerfully we can be affected by random events. The lesson in this is to seize every opportunity.