The Hobo Concerto

by Steven K. Roberts

From Montana to Washington

September 25, 1988

Listening to a sampler album, I am taken in by texture… only to be cheated time and again by fade-outs, false resolutions, and a sort of musical sleight-of-hand designed to leap from intro to outro without wasting a moment in subtlety. In the middle of all this, Maggie clears the candlelit salad dishes. “Ready for dessert?”

“My life is an endless quest for dessert,” I tell her. “That’s what destroyed my marriage.” I smile ironically as the music changes again… damn, how many teasing snippets of greatness can they cram into one CD? As many lifetimes as I can fit into a journey? This is like a VHS sampler of climactic moments from a blue movie publisher: a succession of come-ons. Is this also the essence of Computing Across America? Is my lifestyle the “combo platter” of life’s menu?

Damn straight it is. And this last month has been an orgy of salivation, of music and apple bavarian torte, of sweat and technology, of brilliance and beauty. The road swirls around me like an expert lover — no, like dozens of them. Every day enchants, teases, lures, and promises… only to yield like this patchwork CD to another theme, another flavor, another time. Rodrigo to London Derriere in an instant… then on to Rachmaninov and a syrupy bastardization of Simon & Garfunkel. From hippies to hams, from wild nights to wilderness, from inspiration to depravity without a moment’s segue. I guess this is my life now: a generalist’s wet dream. That explains the cynicism from certain quarters… and the wanderlust sparkling in the eyes of the restless.

This CAA adventure, whatever its current form, is tasting without commitment — a life of mad diversity free from promises. And if I leap from prelude to curtain call with but a passing nod to the elegant recursion of thematic development; if my tales seem like an order of salmon mousse dijon with plum bourbon peppermint sauce and a couple of apple-beet jalapeño fritters on the side; if my life seems a gallery of computerized comic impressionism… then what the hell? This here, folks, is literary escapism at its maddest — a cinéma-vérité of the information age. I don’t know what’s next any more than you do.

And so it’s an unusual night in rattlesnake country. Live C&W “Diggin’ up Bones…” wafts through a sea of RVs; kittens dart between the legs of cooking Maggie; Timmy reads Nietzsche from his publication, The Weekly Freak (infrequently weekly but frequently freaky); Steve provides primal rhythmic undercurrents with his tapo drum; Emily smiles from a soft sea of dark hair. Camping with the hippie hitchhikers is a stab from the past… memories of standing for hours on entrance ramps, of pack clutter, of uncertain nights, of brothers on the highway. The culture is still alive.

Westbound in Montana. Maggie drives the bus; there’s jazz on the stereo. The other eight of us sprawl on the bed… all asleep but me. Three kittens and a Biscuit, Wafer twitching in kitty-dreams. Steve and Tim, curled symmetrically, long blonde hairsprays flowing over familiar pillows. Pretty Emily, dozing, bouncing gently to the Montana highway and distracting my eye from the HP screen. <pang>

Yes, the hippie culture is still alive. We picked them up in Bismarck, three freaks with a “Seattle Please” sign, overloaded backpacks, amulets, anklets, beads, and tie-dye. They’re young — late teens, early 20’s — not carryovers from my salad days at all but a new crop of youth without the perms, spikes, MBAs, crosses, pick-em-ups, or Reeboks that identify the major teen subcultures of our age. They’re hand-to-mouth hippies, just like in the old days, getting by on underground publications, minor crafts, waitressing, odd jobs, and luck. I find it somehow refreshing.

We’re camping in Columbus, Montana. The dipole is a thin gold gleam 40 feet above the campfire, and the radio squawks sideband chatter from most of the US. My weak signal has picked up a few db by originating in Montana, while our crew of five has been joined by three girls from town. Our guests are mingling to mutual astonishment.

“I saw this thing on TV about deadheads, you know? Are you guys, like, well, you know, deadheads?”

“Yeah, we’re deadheads…” Steve and Tim roll their eyes subtly.

“Well, is it like a band, or what?”

Suppressed giggles. “It’s a band.”

“So what kind of music is it? Like, is it Christian, rock, heavy metal…?”

They try to explain, dealing in metaphors that could only mystify. I jump in: “Think of the Grateful Dead as the DNA of the hippie culture — the cultural side of all this is more important than the music. Every other phenomenon that was born then has since withered or evolved into something else… but the Dead is still there, a focus not only for survivors of the era but a magnet for those who have come along since.” I gesture to our new friends.

One girl, 17, blonde and wide-eyed, frighteningly provincial but still harboring a promising vein of curiosity, is in deep awe of all of us. She senses something stirring inside, an awareness that there may, in fact, be some choice in matters of lifestyle (gee…). “Everything is so planned out,” she said, “I know I’m going to college next year, and I know I’ll be at Brian’s Saturday night.” What she meant but couldn’t say, of course, is that her hairstyle, clothing, speech patterns, life expectations, beliefs, and intellectual potential are programmed as well.

We sit around the fire in Itch-keep-pe Park, a lovely relief of tall trees along the Yellowstone River surrounded for miles by low hills, rocky scrub, and drought-ravaged croplands. The local girls see us as a wild and exotic phenomenon, a rare glimpse of the outside — hitchhiking hippies en route to the Dead concert in Eugene and high-tech nomads wandering about with talking bicycles and publishing gigs. After the flow of philosophy and spirited banter, after we bared her wanderlust as if we were a Marion power shovel and she a Marissan cornfield, she spoke…

“This is the happiest day of my life.”

The bus carries new scars, deep gouges on the hood from flying crescent wrenches. Evidence that I’m tiring of this machine lies in the casual shrug with which I accept such injuries — yeah, yeah, so what… as long as it didn’t break anything that will cost money to fix. The occasion this time was the antenna’s “throw-wrench” stuck high in a tree…. and an inspired rescue scheme involving an irresistible force and an immovable object. I just started backing up, stretching the nylon antenna-support rope… until the wrench whistled past the heads of our friends and penetrated the steel of the bus. Hmm. Coulda been grim.

Now it’s Anaconda, Montana: once a thriving mill town, now in the throes of the slow death that comes when the company takes its business elsewhere. The union (the same pushy union that single-handedly created the PVC pipe market by forcing up the price of copper) is the culprit… Anaconda decided mid-strike that it is cheaper to ship Butte copper ore to Japan and haul ingots back across the Pacific that it is to smelt it with union labor 35 miles away in Anaconda. The town, now, is hoist on its own petard.

And so this inbred place born of copper smelting grapples with the reality of a failing economy. Protectionist policies among merchants intimidate new business… those few who try to bring about change are threatened or harassed. Prices are a strange mix of high and low: expensive retail goods and a falling real estate market. People can’t afford to leave, but they drive to Butte or Missoula to shop. The only possible salvation would be an influx of refugees from suburbia, come to create a ski area like the ones that transformed countless Rocky Mountain mining towns.

In the meantime, there are attractions. The Fairmount resort has hot springs and a good water slide. There’s history in the hills, along with arsenic and other goodies. And there’s Ken, K0PP, a “big gun” ham radio operator with a head full of ideas and an antenna farm to die for.

We’re here for a week, the hitchhikers long since off to the Dead concert in Eugene and points beyond. This time it’s a culture shock of the radio world — a meeting between a bicycle-mobile whisper in the wilderness and a high-powered shout from the mountaintops. I’m used to waiting patiently for other stations to call CQ, knowing that they’ll be straining through the static for calls, hoping that a snippet of my speech can be detected before some kilowatt pegs the meter. But Ken here is one of the kilowatts, driving beams atop high towers, ionizing the big Montana sky… and he’s in a location rare enough to make even the most jaded of ham ears twitch.

“Try it,” he said with a twinkle, tuning the linear up on 20 meters and shoving the microphone in front of me. Immediately, I fell into a relaxed chat with a fellow on the east coast… who gave me a signal report loosely comparable to being in the same room, shouting in his face. When I bid him 73 and reached for the dial, about four stations called me at once.

Within moments, I was on the hot seat — racking up contacts in a sort of frenzy, sweating, buzzing with excitement. Now I see why guys go off on DXpeditions! “Tango alpha, go ahead; X-ray India, you’ll be next.” What power… so many people wanted to talk to me that the response to each “QRZ?” was a meter-pegging roar of mingled voices. It got so I felt guilty when one of them turned out to be an intriguing fellow in Pennsylvania, living on a farm with extensive solar and wind power systems. By the time we had chatted for about 20 minutes, I gave in to the silent pressure from the invisible queue of stations needing a rare county in Montana. It’s a strange culture, out there on the airwaves… and like the one here on land, it contains wild extremes that hardly even recognize each other as participants in the same dance.

Speaking of which, I’ve just had a telephone clash with my most vocal critic (take a guess). We’re in Anacortes, Washington, engaged in spirited barter of intellect and energy with Bill and Evelyn Mathauser. Bill, about 70, is a sparkling and energetic wizard of mechanical engineering — the creator of the hydraulic bicycle brake and a host of other projects over the decades. He neither acts nor looks his age… and I wouldn’t be surprised if he could out-pedal me on a cross-country sprint.

The details are unique, but the nature of the relationship is typical. We stay for a few days, exchanging the products of our skills in a complex whirlwind of wild ideas and problem-solving. Bill and I disappear for hours into the shop, emerging grimy and grinning to eat and discuss patents, quality, marketing trends, hydraulic couplings, op amps, strain gauges, politics, trade shows…

And when it ends and we pack up, when the cords are coiled and the fridge bungeed shut, the familiar parting scene we have come to know so well will occur. Bill and I will shake hands, hug the ladies, thank each other, and promise to follow up on some of the more intriguing specifics. That’s the basic barter of our nomadic life — and the essence of our long-term security (deep relationships and mutual respect are more universally bankable than deep mortgages and mutual funds).

But ah, the critic. In a birthday phone call tonight (mine — 36) the attack started. “When are you going to stop leeching off people? You can’t go on taking advantage of hospitality forever, you know. So do you just hang around for three weeks and then get kicked out on the street? If you’re so social, why couldn’t you find time to visit your own cousin in Boston last month? Do you ever plan to grow up, or are you going to live on handouts all your life?” Etcetera.

It occurred to me in the midst of it all that I can count on one hand the overnight visits that occurred in my childhood. Ours was a clean and stable home, but not a particularly social one; relatives were far away and drop-ins were discouraged. The rare invited guest was cause for days of panic about the imagined mess, then subjected to a barrage of hospitality that struck me, even in childhood, as foreign. When I had my brief obbligato flirtation with the curious custom of marriage a decade after moving out, it was the clashing of alien cultures: her family was big, busy, casual, and loud. They even played horseshoes and welcomed unannounced visitors, and they found my parents every bit as strange as my parents found them.

I mention all this because Maggie and I are daily reminded of the diversity of social patterns in this country — a giant place that may appear homogenized on the surface but is in fact a mad tangle of non-miscible behavior patterns. Families beget expectations about how the world out there works, and it is as hard for children to escape this programming as it is for parents to grapple with the occasion of their doing so.

In general, this is an amazingly social land. Here and there are paranoid, closed minds that refuse social intercourse beyond the safe haven of old friends, but most people welcome at least a glimpse of the outside world (as long as it’s not too weird). Most important to our nomadic adventure is the fact that every community harbors a scattering of exceptional people who thrive on learning, welcome surprises, seek new friendships, enjoy barter, consider alternatives, and otherwise prefer to stay alive at some level beyond the fevered maintenance of a featureless status quo. I’ve tried to find some career correlation here, but I cannot: in recent experience, this meta-class has included an inventor, a surgeon, a power engineer, a wealthy nursing home magnate, a men’s clothing salesman, a printer, a photo marketing expert, a writer, an antenna designer, a grade school teacher, an entrepreneurial millionaire, a few computer people, a hand-to-mouth ex-hippie, and at least one totally loony kindred spirit who gets by on the random fruits of intelligent generalism. We’ve stayed, and shared deeply, with them all.

And THIS is our real family — every visit a reunion, every parting a poignant moment of energy-enriched sadness. Free exchange of skills and ideas is the very lifeblood of our culture, and it spawns a kinship that some people will never understand.

While we’re in a mood for social commentary, by the way, I really must make one passing comment on this insane ‘88 election. Why is it that I have yet, in all my travels, to meet even one person who is unmistakably in favor of either candidate? Could this perhaps suggest some kind of flaw in the political process? I mean… how did these guys get in this position if nobody likes them? What would happen if we all stayed home on election day?

Yes, these are disturbing times, alright. There have been a lot of reminders recently about our continued misbehavior, as a species, where the environment is concerned. Things seemed hopeful about ten or fifteen years ago, when there was a popular outcry in the name of ecology.

The key word here is “popular.” We have a fickle press, a fickle national mindset. Things just don’t stay interesting for very long: if you keep doing news stories about pollution, people will eventually get bored and change the channel. “Yeah, boy, remember that energy crisis a few years back? I’m glad that’s over.” You hardly even hear any Ethiopian jokes any more, ‘cause everyone knows that African starvation has either been taken care of or is just the way things are. And the environment, well, “greenhouse effect” is a popular word now, but it will go the way of mercury, dolphin, acid rain, dioxin, and all the rest. Just vaguely unpleasant words that recall a flood of special reports on the 6 o’clock news.

Unfortunately, all that is catching up with us in the midst of our national obsession with personal bottom lines. The recent drought was a useful reminder, but it takes a real kick in the ass to get the public’s attention. That one wasn’t nearly hard enough — we’ll need something on the scale of global climate change to rearrange the priorities of governments and make people realize that the earth is an island.

The frustrating thing about all this from the standpoint of a reasonably involved writer is that editors filter the news to fit current tastes (as dictated by sales figures). “Too much gloom and doom,” one recently told me, slashing some commentary on global perspective. Okay, boss. Next time I’ll write about the Dust Bowl Diet.

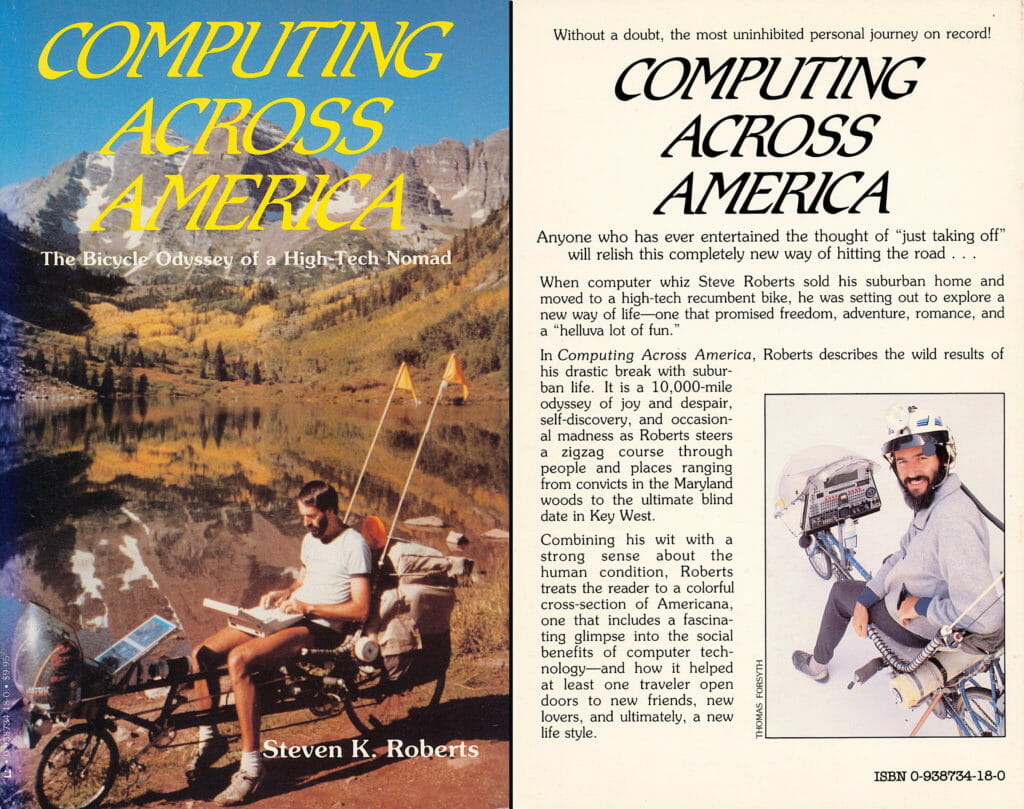

Oh yes, publishing. (Hey, this is kinda fun — I feel like Andy Rooney.) As you may know, my little nomadic business has gained a bit of stability lately in the form of the Computing Across America book. I finally have a product more substantial than the deadline-driven, personality-sensitive, stylistically limited game of freelancing. I have a book. A widget. A product. And as long as I keep selling ‘em, the publisher will keep printing ‘em.

I won’t bore you with the endless absurdity of the publishing business, for like most businesses it is filled with grim details, cronyism, shallow motives, and even a few honest and intelligent people. But if you’re reading this, you’re obviously a reader — and probably not a typical one. One issue therefore affects you very personally.

Have you noticed any recent changes in the fare offered by McDalton and McWalden? Can you tell what city you’re in by walking into one of their stores? Do you ever look for something beyond past and present best sellers, self-help guides, coffee-table books on sale, and the usual staples in familiar departments… and find yourself frustrated?

If your answers were yes, no, and hell yes, then you already know the problem. The major chains, those omnipotent dictators of popular taste capable of creating an overnight bestseller with a single stock order, have taken another step toward the homogenization of American intellect. By explicit corporate policy, B. Dalton now only buys from publishers who have more than five titles in their current trade catalog. In addition, they do all buying through New York — that provincial megalopolis of the publishing industry. What this means to us readers in the American boonies is that no local books will appear in the major stores, nor will any titles of a specialized or esoteric nature. These they will only order with great reluctance, for the wholesale intermediaries impose such a margin that there’s simply no money in it.

My advice, if this is at all irritating to you, is to deluge your local literary fast-food outlets with insistent requests for special service — then take your business noticeably elsewhere if they don’t perform. As far as I can tell from this perspective, money is the only thing that still talks in today’s world of arts and letters.

Somehow, though, all those frustrations seem less maddening here in the northwest. I had forgotten the beauty — the green tunnels over rain-slicked roads, the dramatic confluence of mountain and sea, the sense of almost primordial timelessness. Bill Mathauser, between revelations of machining brilliance, told a story about his father in law.

“The old man was from Arkansas, and he spent his whole life back there in the lumber industry — at a big mill, I think. He came out here for a visit before he died a few years back, and one day asked me if I’d take him out to see the redwoods. “Sure, dad, sure,” I told him.

“Well, the next day we piled in the car and started driving. The old man fell asleep, and when we got to the redwood forest I found the biggest tree I could and parked right next to it. The thing was, oh, as big as from here to that wall over there — a good sixteen feet or so. ‘Dad? We’re here. Wake up.’

“‘Mmf? Where?’

“‘These are the redwoods.’ He looked out the window for a moment, then got out, staring at the tree. Then he started backing up, craning his neck to see the top. Finally he just stopped and stood there… and began crying. It was more magnificence than he could handle.

“That night, around 2 AM, I heard him mumbling in the bathroom. I thought maybe he was sick, so I tiptoed over to the door and peeked in. There he was, sitting on the can, shaking his head and repeating over and over: ‘They’ll never believe me. They’ll never believe me…’”

Obviously, the human encounters continue to be the heart of this adventure. At Larsen Antennas in Vancouver, I watched resident wizard David Phemister spring into action — applying an intuitive understanding of RF black magic to the bike’s special radiation problems. I now have a 3-section mast with coiled radials, and it rakes the sky with colored flags and exudes the low-powered whisperings to which I have returned since leaving Anaconda.

Also in Vancouver, a delightful cycling surgeon — and the man behind the annual “To Hel’en Back” bicycle tour) deftly excised a Maggie-glitch and treated us to a few days of country living… complete with a pit bull named Gator. The cats found the beast horrifying enough to abandon their usual wanderings, and they huddled pitiably together in the bus, hissing and bristling through the windows at what turned out to be a remarkably gentle giant. (And to Roger, if you are out there… a long-overdue thank you for the superb hospitality, fascinating conversation, and articles in the Wheel Truth!)

Now? What now? We’re southbound this week, a round of meetings with Seattle-area equipment sponsors now history. Big conferences lie ahead… the next chapter should offer a peek into the mad, eccentric subculture of hackers. This gathering in Saratoga will be the antipode to COMDEX in the topologically tangled computer world — a refreshing and perhaps frightening three-day tumble with the minds that spark technology’s future. Ooh.

Cheers from the islands…

You must be logged in to post a comment.