An Interview With A Mac-Using Pioneering Technomad

Conducted by Eolake Stobblehouse

The Mac Observer

April, 2001

Steven K. Roberts is famous for being the computer geek (sorry, genius) on a bicycle. In the eighties and nineties he travelled America on three heavily computerized and communicating bicycles, culminating in the technically impressive BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine Only Too Heavy).

After that Steven went after the obvious goal of computing and communicating on inland and nearland waters, building the one-person floating micro-technology wonder: the Microship.

Do read A Day In The Life Of A Technomad. it reads like science fiction, but it is real.

Macintosh machines and other technological wonders transform The Wild into The Wild And Connected. (Most of the Mac talk is in the second half of this interview, but don’t miss the other cool stuff.)

The Mac Observer: It would seem to me that the essence of both your computer-cycle and the computer-ship is to make a compact, mobile unit, as independent of exterior support and energy as possible, capable of a lot of computing capability, and in continual communication with the world electronically. Is that right?

Steven K. Roberts: Yes, though that’s not so much the purpose as the design spec that is derived FROM the purpose. The more philosophical goal is to be able to maintain a full-time technomadic existence… a wandering life that incorporates tools that render physical location irrelevant. This was successful to varying degrees with the three versions of the bike (especially when I wasn’t getting seduced by the Siren of Complexity, always a temptation), and has been fine-tuned since into the core premise of the Microship project.

I should also mention that fun is the bottom line, though that takes many forms in addition to the obvious frolicking with the current on sunny days. We’re streaming environmental and internal system data to the web, publishing nautical yarns, producing video about the adventure, hacking for the pure joy of it, playing with nomadic community ideas, and otherwise constructing an adventure-based lifestyle out of our passions.

All this translated, after a few inevitable forays in the wrong direction, into the actual Microship design spec: tiny amphibian escape pods capable of open-ended wandering along coastal, inland, and protected waterways (not ocean crossings or whitewater!). Sleeping on-board has to be possible, as does human-powered haulout; this seemingly innocent pair of requirements brackets the physical scale of the boats to a very narrow range, yielding a custom 19i folding trimaran using a canoe as the center hull, fitted with deployable hydraulically controlled landing gear (an engineering nightmare).

In addition to a platform of suitable scale for human power, I decided early on that these little boatlets have to carry multiple independent modes of propulsion: pedal drives, steerable solar/electric thrusters, and freestanding sails. There’s a retractable seat in the cockpit to allow on-water bivouac, and an environmentally sealed control console contains all the electronics. My boat is optimized for networking, data collection, and communications; Tasha’s carries a digital video editing system along with a variety of on-board cameras including a steerable video turret.

We also have satellite, cellular, HF, and opportunistic 802.11 networking tools, along with a fairly robust ham shack and other voice communication links. The boats are tightly networked to each other as well as our backpacks, so the whole Traveling Circuits feels like one integrated system. “Messing about in boats” has never required so much technological infrastructure, but that’s life at Nomadic Research Labs!

TMO: It seems to me that with all that technology on board, you are dependent upon civilization under any circumstances, so I wonder why you didn’t go for motors instead of pedals and solar panels?

Steven K. Roberts: I find them noisy, difficult to maintain, smelly, and generally unpleasant in the otherwise magical environment of the water… especially since I came at this through kayaking and sailing, not stinkpotting. There are definitely times when it would be nice to have more horsepower available (like fighting contrary currents at sunset with a lee shore), but in these tiny boats, all that weight and nasty fuel would be a drag. And 2-cycle engines, which would inevitably be the most appropriate scale, are particularly evil polluters, collectively responsible for 7-12 times (depending on who you listen to) the Exxon Valdez spill per year.

I would consider a fuel cell to run our electric thruster, however….

TMO: Your site is a real geek-adventure, with long pages of technical stuff, which frankly is over my head. My slant is more philosophical. Even though I am a real city/indoor person myself, I am excited about the near future possibilities of computing and real-time connections anywhere on the planet. Where do you imagine we will be in this respect in ten years? In twenty?

Steven K. Roberts: I think it’s getting better and better. Now that a broadband connection is nestled in the middle of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, there’s more and more competition in the market for fat pipes. Here on Camano Island, Washington, where our dialup options are abysmal, we use a Starband satellite connection… and on the boatlets we use Globalstar. With more and more wireless terrestrial and satellite pipes coming online, early growing pains notwithstanding, it’s getting easier to be truly remote and yet reasonably well connected. Of course, we end up paying more than our cohorts in the cities, but we don’t have to put up with unrelenting noise, traffic, bad air, economic stresses, and so on…

My gut feel is that our own rather extreme technomadic lifestyle is a sort of caricature of something that will become increasingly common — a gradual decoupling, even if only temporarily, from fixed physical facilities and hardwired connections. After all, once you move to the Net, you can put your body anywhere you like. Enough people find this interesting that the market will inevitably follow.

TMO: How do you think the cycle and boat might influence the development of independent computing and communication? Again a decade or two into the future.

Steven K. Roberts: If experience is any guide, I think our real role here is to serve as a public demonstration of what’s possible (while not getting distracted by that in any way that detracts from the amusement). When I started wandering on the Winnebiko in 1983, the media went nuts in every town I visited… “Wow, why would you need a computer on a bike?” The notion of physically decoupling and running a business while traveling was completely alien back then, and doing it on a recumbent bicycle with solar panels just made the image indelible. Look how far we’ve come in 18 years: one could probably be newsworthy now by riding a bicycle across the United States WITHOUT a laptop. “Wow, how do you get your e-mail? Surely you don’t depend on cybercafes?”

We tend to be agents of future shock, pulling together a wide range of existing technologies that haven’t yet reached public awareness, then using them to create a new kind of lifestyle. I can’t imagine there would ever be much of a market for full-on BEHEMOTH or Microship clones, but the various memes that fall out of the adventure do take on a life of their own (as evidenced by countless pieces of e-mail over the years blaming me for radical lifestyle changes and the acquisition of new toys! <wicked grin>)

TMO: Often, the most important developments are difficult to see the importance of (an obvious example is that hardly anybody in the seventies imagined that personal computers would ever be important, or big business). Still, I have to ask, what kinds of future applications do you imagine for the research you are doing? (Let’s face it, it is research.)

Steven K. Roberts: That’s an interesting subject. I tend to be rather bad at the business side of all this (well, OK, I’ve managed to survive with only 11 months of employment in the past 25 years, but still… it’s a hand-to-mouth existence). I keep waiting for some mythical “technology transfer joint-venture partner” to materialize in my life and productize all the potential BEHEMOTH and Microship spinoffs — the crossbar networks, user-interface hacks, mobile data-collection client and server software, embedded Squeak, wireless graphic front-end tools, multichannel solar peak power tracker, hydraulic controls…

But I think it’s more subtle than that. These projects tend to be massive integration exercises of mostly off-the-shelf subsystems, knitted together with custom code and, only where absolutely necessary, custom hardware. Most of the work is in packaging, device selection, sponsorship development, and — did I mention packaging? 😉

What falls out of Nomadic Research Labs more than anything else, I think, is a sort of applied generalism… we don’t have the budget to be specialists and wouldn’t be good at it if we did, so it’s essential to explore a wide range of industries in order to save ourselves work. This is the precise opposite of the “not invented here” syndrome… if it is invented here, there better be a damn good reason. This has to be the response to severely limited resources, or you die.

I don’t mean to imply that there’s no innovation here… quite the opposite. But the biggest hack of all is integration, something that is hard for most companies to do because they are, perforce, focused on their own products.

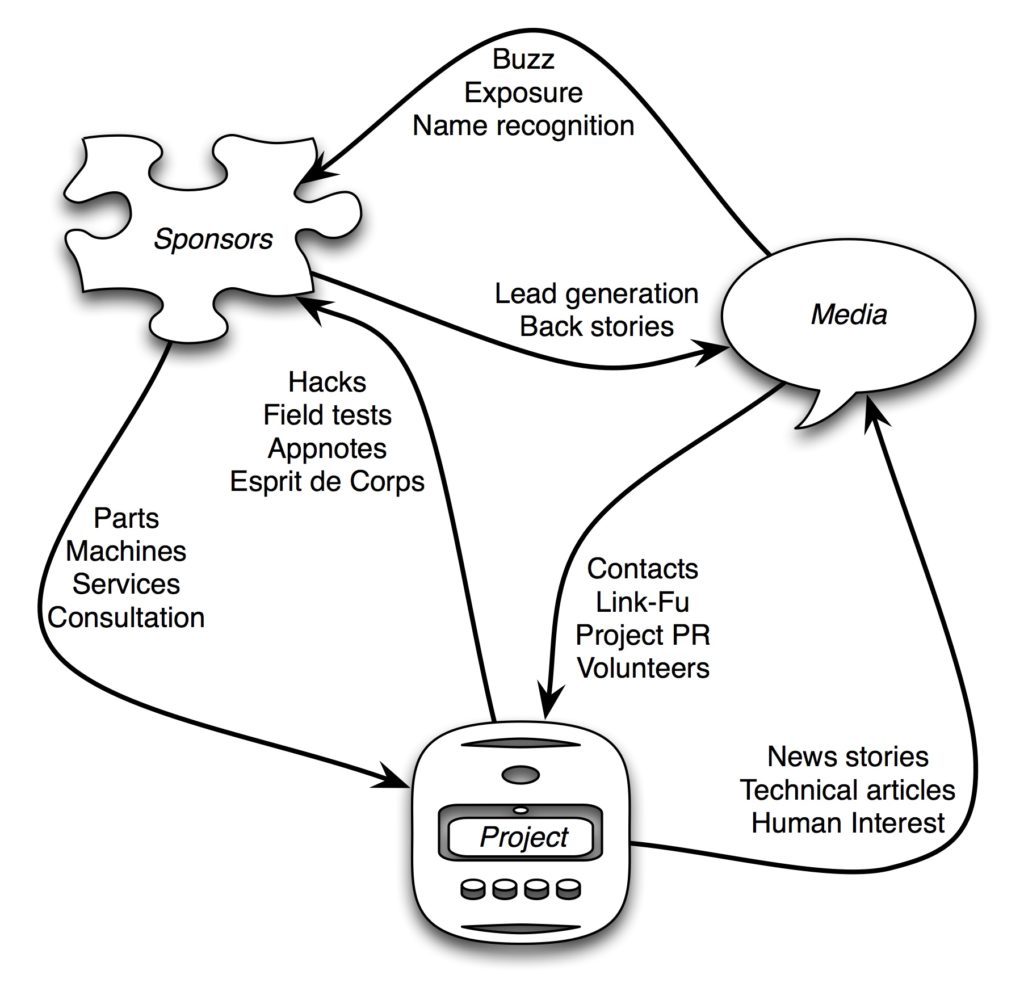

What does that all mean in the context of your question? If anything, I would say that our greatest legacy is a way of thinking about system development that flies in the face of traditional methods. We depend on over 130 sponsors, a huge range of vendors, and an international team of volunteers (many of whom take advantage of our “geek’s vacation” program and take a break from their real work to come here, live with us for a week or two, and remember why they became engineers).

TMO: How long have you been using Macintosh?

Steven K. Roberts: I met my first Mac while on my first bicycle trip, in the summer of 1984 (I had played briefly with a Lisa, and also the machines at PARC that inspired the project). I acquired my first Mac in 1986 and have owned, oh, let’s see… about a dozen since then.

TMO: What is your current Mac? What is your dream Mac?

Steven K. Roberts: The machine I live on most of the time, which has developed a patina of wear like old jeans, is an early G3 PowerBook. Natasha has an identical unit, and there’s an iMac DV in our media lab as well as a couple of older boxes on our LAN for guest e-mail, backups, and random little jobs. Like every other die-hard Mac user on the planet, Natasha and I are lusting after Titaniums <whimper>…

TMO: I understand you were forced to install your first Windows system in order to solve a recent networking problem… from the perspective of a long-time Mac user, what was that experience like?

Steven K. Roberts: Horrific. How do those people make so much money? I’m so used to tools that don’t constantly insist that I pay attention to them that configuring proxies and such in a Windows box was like going way back in time… only worse, given all the added complexity. Some of this can of course be attributed to my relative unfamiliarity with the platform, but there was a pervasive lack of grace that made the whole experience unpleasant. Now it’s sitting over there, screen off, requiring a reboot every couple of days (and not always smoothly). Once someone cobbles together suitable code for the Linux environment, I’ll drag Windows into its own recycle bin and rearrange all those bits into the latest Debian install. It’s still a lot more confusing than the Mac, but at least Linux has an overall feeling of robustness about it… not to mention an interesting user population.

It’s weird, isn’t it? Doing something on the Windows box was akin to having to tweak my cam timing and fuel injectors before driving to the store… I’m used to just jumping in and going. I have non-technical friends — artists and realtors — who know about interrupts and DLLs. What’s wrong with this picture?

Incidentally, that networking problem you alluded to was the installation of Starband satellite service and making it accessible to our LAN. Starband is quite cool, especially if you don’t have DSL or Cable… but the unavoidable latency issues of a 50,000-mile round trip for all the bits require special proxy software to accelerate transfers and minimize verbose handshaking. This code, at the moment, only exists for Windows <sigh>.

TMO: Wasn’t one of the built-in computers on BEHEMOTH a Mac? According to your Web site, there were also three integrated DOS boxes as well as a SPARC and a Mac laptop in the trailer… how was the experience of using these different systems in practice?

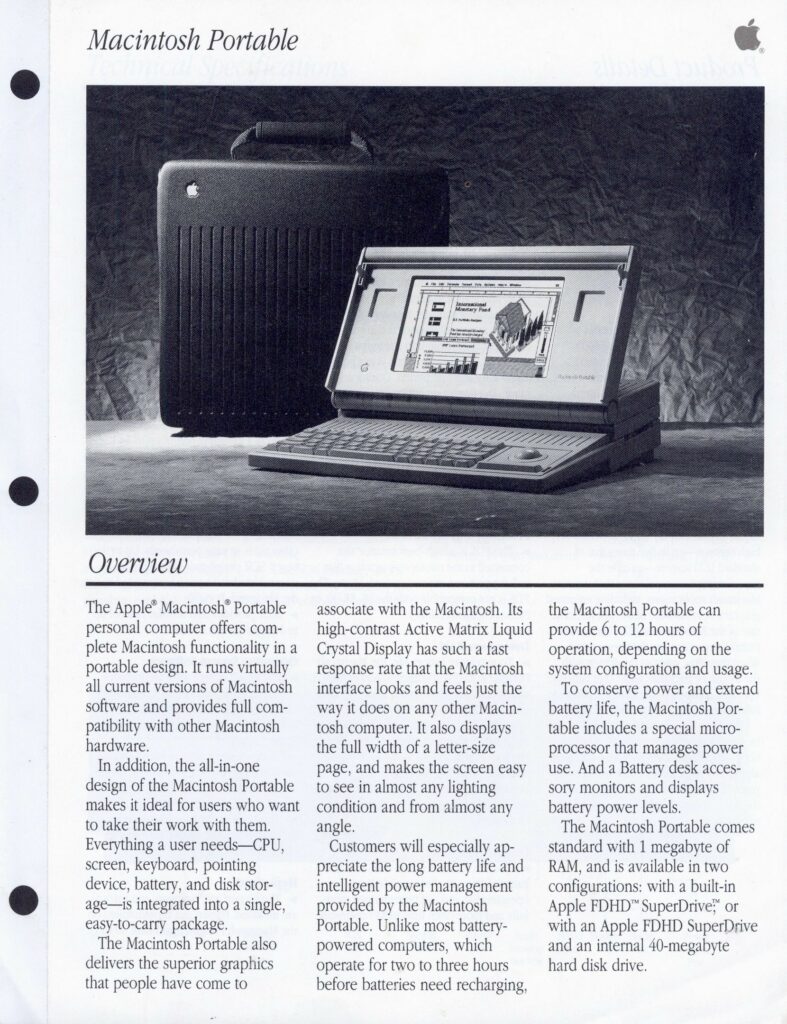

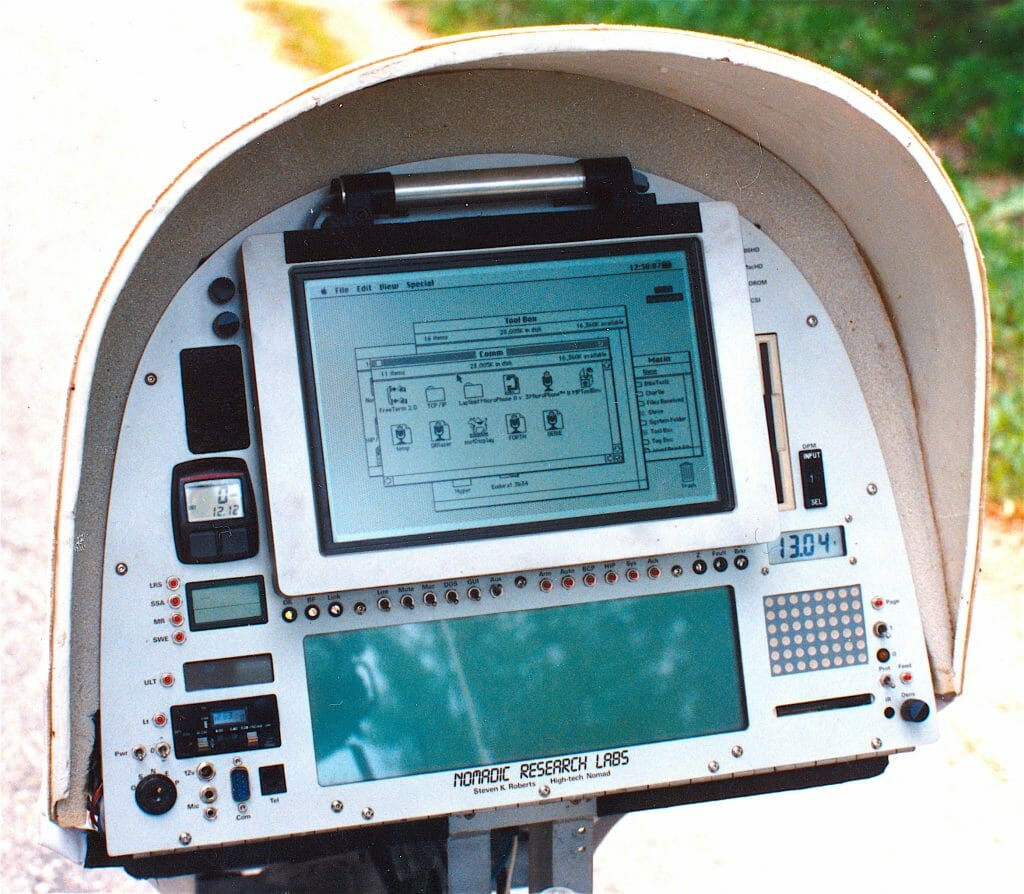

Steven K. Roberts: The bike’s primary work environment was a hacked Mac Portable (the original 68000 unit with a 40 MB hard drive… which seemed like a huge luxury at the time). The screen (which looked great in direct sunlight) was repackaged in a sealed aluminum hinged enclosure, which could be lifted to reveal a backlit VGA screen for a 286 PC (I called it “mechanical display paging”). Through no fault of the PC itself, it never actually got used on the road… I couldn’t even tell if the screen was turned on once it was out of the relative murk of the bikelab.

I did use another little Ampro embedded PC that ran the heads-up display in my helmet, mostly for a pop-up database and a few other hacking tools. All my writing via the handlebar chord keyboard and the ultrasonic head mouse was done on the Mac, however… as was e-mail, using the first public version of Eudora, hacked to work through a Qualcomm OmniTRACS satellite terminal. In 1991 I had live e-mail on a bicycle…

The “big iron” was a SPARC in an enclosure behind my seat, though that didn’t get well enough integrated to be accessible while riding. I did briefly use it for PPP via a CellBlazer, which was pretty exotic at the time. At least I could say I was riding a unixcycle, which confused people. <grin>

My primary personal machine on that trip was the PowerBook 170 in the trailer… I could plug it into the bike’s AppleTalk and move my stories over from the console machine, edit them with more attention than I could give while pedaling, and upload as needed.

TMO: Reading about the computer systems of the boats, there is a lot of talk about Linux and such. So does Macintosh have a place on the Microship project?

Steven K. Roberts: Absolutely! Linux makes sense for the boat’s embedded control environment, database server, networking tools, and so on… though for the big-iron I am thinking more and more of dropping a suitable PowerBook with OS X into a padded slot, remoting the LCD, and using it as is. There is a tiny embedded system running Squeak that’s on all the time, but that’s in a whole different machine class (we’re shooting for 1 watt)…. the little guy is autonomous unless I need to bring up its bitmap on the big machine to engage in hackage.

But as far as my “productivity environment” is concerned, I’ve been living in the Mac for so long, and the tools are so smooth, that I see no reason to change. Both boatlets will also carry laptops that we’ll use when on shore, and the only challenge is to let the network environment be transparent enough that we’re not constantly copying files back and forth.

TMO: It is against the rules of Mac Observer in the year of 2001 to interview anybody without asking them about Mac OS X. With you being both a Mac user and a Unix hacker, I would be very interested in what you think OS X will do for the Mac platform of the future.

Steven K. Roberts: I must confess that I haven’t had my hands on it yet (I’m slow to upgrade working systems), so this is pure conjecture. But based on what I’ve been reading, the robustness of OS X will move the Mac more into server applications, minimize the impact of application crashes and browser flakiness, and make the machine a better development environment. I’m looking forward to installing it… if it can keep me from firing up even one Wintel platform for unixish apps, then it’s good for the planet <grin>.

If I may drop a footnote on all this… we heartily welcome all sorts of involvement from Out There, and are always looking for experienced developers who want to have fun. Also, I post occasional updates to the nomadness listserv — maximum posting frequency is 1/month and there is no other traffic or list use. If you want to receive tech/adventure tales, use the “SUBSCRIBE!” widget [obsolete info redacted]. Archives and tons of other stuff may be found on the site.

TMO: Thanks, Steven, and best of luck in the future with this truly cutting-edge project.

You must be logged in to post a comment.