Flirtations with Technology

Computing Across America, chapter 32

by Steven K. Roberts

Lake Charles, Louisiana

May 16, 1984

This chapter captures the moment I first met a Mac. I had seen the Dolphin and Dorado at Xerox PARC during an Artificial Intelligence conference in 1981… as well as the Star for business on display at NCC ’81… but this was the first time a bitmapped machine had been offered in the personal computer marketplace (not counting the $10K Apple Lisa released a year earlier). I later became friends with Jef Raskin, who started the Macintosh project… but at this point, meandering along back roads on my bicycle, the machine triggered intense pangs of longing as technology made evolutionary leaps without me.

The computer had spent the night in a tedious wait loop: “Is it seven o’clock yet? No? Is it seven o’clock yet? No? OK, now is it seven o’clock? No? Damn, ain’t it seven o’clock yet? Well then, now is it seven o’clock?” The machine was the very image of frantic impatience, asking this question some 30,000 times a second, checking the data in a WWV-synchronized real-time clock every time around.

And then without a millisecond’s warning, it was 7:00:00.00.

“Hot damn!” The computer dropped into a service routine, twittered an ultrasonic command over to a little box on the desk, and then went back to the ol’ grind — waiting for 7:15.

The box awoke with a start. “What? You want device 4 switched on?” It fired a control signal through the house wiring and went back to sleep.

The porch light listened, but did nothing, for it was device 1. Device 2 was the coffee pot, and it thought about it… but there would be no brewing for fifteen more minutes. Device 3 was the printer, and it just raised a sleepy eyelid and rolled over.

Ah, but device 4! A relay clicked softly in the living room and power surged into $8,000 worth of stereo equipment, charging huge filter capacitors and shaking almighty speaker cones. The digital audio disk began spinning, and the laser head relayed a high-speed data stream to signal-processing and cross-interleaved Reed-Solomon error correction circuitry.

Whereupon the opening trumpets of Aaron Copeland’s Fanfare for the Common Man materialized as if by magic, becoming sound — lots of sound — via a quartet of studio-grade 235-watt amplifiers.

I sat bolt upright in bed. The blazing brass reveille sent dreams skittering like startled cockroaches into the dark corners of my mind, effecting the transition from asleep to awake as quickly as if I had been device 4 myself.

I was staying in the north Baton Rouge home of Dennis, a fellow cyclist-computerist-audiophile who I met at Precision Bicycles (with a rig like the Winnebiko, bike shops are reliable places to meet people). Days began abruptly in his house, and within the hour we were pedaling a lazy back road, heading for the St. Francisville ferry across the mighty Mississippi. “That’s one hell of an alarm clock,” I called over the morning sounds of Louisiana woods.

“Liked that, eh?”

“Now I can really see the value of high-power stereo equipment. I expected the Pearly Gates to open with all those trumpets — it ain’t the volume, it’s the presence.”

“You got that right, but you wouldn’t know it to see the way some people in these parts sell audio equipment. I saw a redneck up in Jackson try to sell a monster system once. First he ran through the standard Willie Nelson demo, then he lit a candle—“

“Sounds a bit spiritual for stereo sales.”

“Not at all. He put the candle three feet in front of a speaker, cranked the amp all the way up with no album, then blew out the flame by flicking the needle with his thumb.”

“Ow! I’ve heard of destructive testing, but destructive demos?“

We went on bantering, enjoying the easy friendship. Over and over I am reminded that the world is full of interesting people. Odd how I failed to realize that back when my social universe consisted of a handful of Columbus friends and a few old pals long gone.

New friends. The only problem with meeting so many is having to say good-bye to so many. This I did at the landing of the St. Francisville ferry, then with a rumbling diesel and curious looks from the crew I floated across the Mississippi River…. one of the psychological dividing lines of the journey.

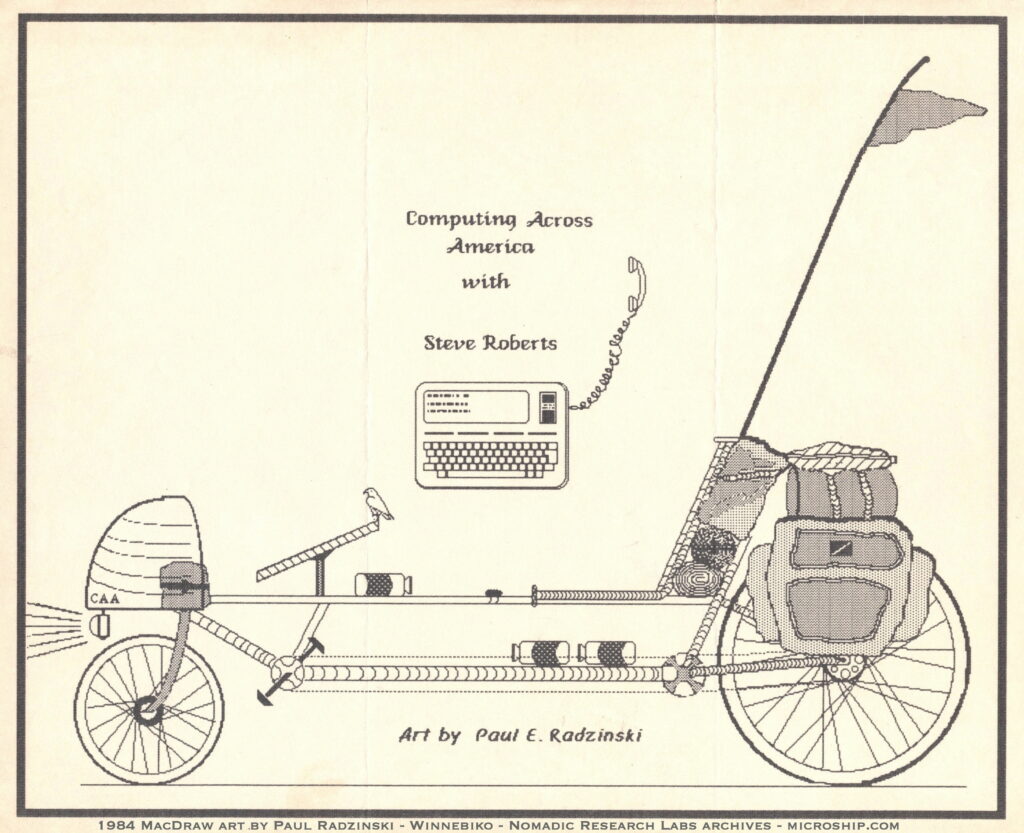

It was in the Lake Charles home of Paul Radzinski that I was destined to develop a serious love affair — with an Apple Macintosh, introduced only weeks earlier with the iconic 1984 commercial. Paul had been the first person to send me an online invitation via CompuServe, and after we took care of the requisite pizza he grinned and said, “Hey, I just bought a Mac — want to give it a try?”

Now, I’ve always been rather blasé about new computers — I’ve lived around this industry for a long time and I’m seldom excited by systems that are just faster or flashier than the previous year’s models. They get better all the time, of course, but their evolution has until recently been along the lines of performance, not philosophy.

One of the big problems with the computer business has always been friendliness (or the lack of it). Traditionally, a human has had to don an intellectual straitjacket in order to deal with the beasts — for computers follow step-by-step instructions without any understanding of what the point might be.

Dennis’ high-tech alarm clock, for example, had to be set with a specific sequence of commands. It took a measure of “computer literacy” to make this happen — not at all like simply asking a person to do the job.

But “computer literacy,” while a trendy notion, misses the point entirely. Why lower ourselves to the level of unthinking number-crunchers so we can talk on their terms? We should make computers intelligent enough to carry on a normal conversation.

“Well, I ‘spose I should get up at seven…”

“You want music or the buzzer?”

“How ’bout Copeland?”

“You got it. Coffee?”

“Yeah, but give me fifteen minutes to wake up first.”

Notice all the assumptions the machine has to make — this simple

exchange calls for much more intelligence and “common knowledge” than is offered by computers of the day. But to most people, that makes a lot more sense than:

DEV4 ON 5/10 07:00:00

DEV2 ON 5/10 07:15:00 The objective of artificial intelligence research is the creation of machines who think. A lot of people find this scary, but the prospect is intriguing — smart computers would be less threatening than the ones we have now. Wouldn’t a modicum of adaptability, a touch of wry humor, and a soupçon of grace have a sweeping effect on their popularity?

Imagine… an electronic pal who gathers mail and information from worldwide networks for delivery with your 7:15 coffee. You briefly discuss a few personal problems, then kick back to read for a while. The computer ambles over with a furry little wiggle, curls around your feet, and contemplates the ontology of n-order spacetime — just to keep you company.

OK, the Mac won’t quite do that, but it’s certainly an improvement over traditional personal computers. It’s more like a video game, in a way — you can undergo a graceful evolution from naiveté to expertise without having to spend hours digging around in obscure manuals. Instead of typing commands or wading through menus, you mess around with things as if they’re objects on a desktop.

I sat in Paul’s office, tinkering with the little gem, realizing that this is the first of a new breed of computers that is emerging from the research labs. I had only been on the road for eight months, but my old feeling of intimacy with the industry was fading fast: like an ex-lover, the technology was drifting out of touch. I saw her there in southwest Louisiana wearing sexy new clothes, and I suddenly felt jealous, wistful, almost hurt.

We had been close once, you know — back in the 1970s when things were simple and address spaces stopped at 64K. But she had matured since the good old days; she had lost her baby fat and become worldly, sophisticated. She was powerfully alluring, but no longer my sweetheart. There was an ache in my chest and a sense that she had moved into the fast lane even as I was lazily drifting along the shoulder on my bicycle.

“Damn, you’re beautiful,” I whispered, tinkering with her fonts and pulling down her special features menu. She danced at my touch, smooth and responsive, her cursor moving precisely as I manipulated her mouse. Teasing me, mercilessly teasing me.

“What are you doing in Paul’s bedroom?” I thought with a small red flash of rage. I was agitated, breathing rapidly — as if I had been invited for dinner at a friend’s house only to discover that his blushing young bride is someone I have been in love with for years.

I suppose I should accept this as one of the costs of the journey: I can’t have it all. I have eloped with the Other Woman.

“I think I’m in love,” I told Paul, hiding my deeper feelings and recalling the last time I had said that — zipping along an Ohio country road on Robby’s Avatar. “I wonder if I can fit one of these on the bike? The Model 100 is starting to seem kind of inadequate.”

“I don’t know, Steve. Will a mouse work in the field?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.