The Austin Phase Shift

Computing Across America, chapter 34

by Steven K. Roberts

Austin, Texas

June 27, 1984

Austinfornia: where hippies and capitalism peacefully merge into oneness and bliss.

Caron DuFrane

Transitions are usually only recognized as such in retrospect, and I was due for one despite having just emerged from my action-packed New Orleans Sabbatical. A phase shift was occurring — not a shift of direction nor even pace, but a different perspective.

This had something to do with the quickening pulse of media coverage. Although there was still the occasional happy news story (“and finally, there’s a guy with an unusual bicycle in town this evening… you’ll wanna see this!”), I was coming to realize that I had stumbled with perfect timing into what was about to become a massive cultural shift. Already some of the articles were nearly breathless, citing the implications of technology I was using to putter through my casual freelance life, and the on-the-road flirtation that had so obsessed me was starting to seem kind of irrelevant by comparison.

I had the infrastructure — the bike, the concept, and a good beginning — and was routinely using tools that were yet mysterious to the general population. But where was I headed? A book contract, mainstream media, and serious new toys on the horizon… it was time to step into my own shoes.

Between all that and the somewhat intimidating specter of West Texas, I decided to take a break for a few weeks and figure out what I was doing. I rolled into Austin, looking for a place to stay.

First impressions were not great: I was greeted with a hostile shout from a passing pickup on Martin Luther King Boulevard. “Get a job and buy a car, motherfucker!” cried the stubble-faced macho cowboy, leaning out of the window and clutching his can of Lone Star.

(“This is my job, and my secretary drives my Rabbit in Ohio!” I shouted back with a smile and a wave, but he was gone…)

There was much more to Austin, as it turned out.

From my perspective at the time, the city had everything: co-op housing, urban sprawl, nouveau-tech, anti-tech, fervent evangelism, hippie capitalism, strange cults, music in abundance, a sailboarding society, food from Tex-Mex to Sushi, deathy punkers, computer networkers, counterculture book stores, one of the world’s finest swimming holes, nude beaches, spectacular bike routes, nerds, drag worms, wizards, politicians, and Primo burgers washed down with Tecate at the late Mad Dog & Beans. Random on-street encounters were almost always interesting.

This is the brain of the Lone Star State, not the biggest city in Texas, but definitely the place to be if you have the kind of energy that makes you hungry for growth.

The results are many. There is so much high-tech here that many hopefuls call it Silicon Prairie. Money flows into the UT campus, entrepreneurial ventures, and research firms. The city grooms itself; the media support it. People flee to Austin from the mad overload that is Houston; they come as wide-eyed pilgrims from small Texas towns. They even come from California and the Rust Belt, drawn by high-tech and low tax.

Naturally, they’re not all welcome — Austin might be growing a little too fast. I met one impoverished student who planned to cash in on the growing resentment of northern refugees by running a newspaper ad: “Yankee wants to go home! Please send donations.”

There is bitterness about the razing of the Armadillo World Headquarters for an IBM building, urban sprawl, panhandling drag worms, and the other economic pressures of a fast-growing population. But a lot of people do more than complain, and the co-op culture is a perfect example.

For my first few days in town, I felt like a sperm cell trying in a frenzy to gain admission to the Egg, probing with my long skinny bicycle for a point of entry that would bear fruit. I sampled a home or two, even a hot room in a Rodeway Inn over a Safeway parking lot. But the couch circuit gets old. (Besides, this is a town with a lot of transients. People are wary.)

A bit of advice introduced me to the co-op culture. It’s a growing phenomenon here: low-cost housing jointly owned and managed by its own residents in a common-law marriage of democracy and small-scale socialism. The buildings range from ten to over a hundred people, and $300 to $350 a month (this was 1984) buys not only a room but three meals a day and free snacking.

My first co-op was an old building, a place with the leftist flavor of late-1960’s campus activism. I was shown to my room, a seedy affair of paint-encrusted screens, broken windowpanes, bare floor, and cluttered view. In a hastily called house meeting of half the building’s thirty or so residents I was admitted to their society… not without bitter discussion about “temporaries” who left a legacy of unpaid phone bills. With casual adherence to Roberts rules of order, the members kept themselves just on the brink of anarchy, the chair finally stopping chitchat with the words, “OK, now let’s have a formal little vote.”

I was in.

The next day I worked in the dining room with the computer before me, struggling with a USA Today assignment. My ankles itched from flea bites, and distorted music careened out of the kitchen where two residents were making something out of sunflower seeds, avocados, beans, and zucchini.

A painted banner on the wall proclaimed LA LUCHA SIGUE (the struggle continues); a poster said, SANDINO VIVE EN LA LUCHA POR LA PAZ! Bulletin boards carried schedules of spring cleaning.

But there was a sense of purposelessness — some folks sprawled in the TV room, others half-heartedly did chores. I relocated to a second-floor deck, my desk a sun-bleached lavender steel tabletop wobbling atop a cable reel. A door creaked in the hot wind and an articulate guitar wafted from one of the rooms, the notes crying, imaginative counterpoint bringing a smile to my lips. It was a fascinating glimpse of a subculture, but too lazy for the high-tech crackle of media and projects that I needed to sustain. Between that and the fleas, I was back on the street three days later.

My second co-op was the Whitehall. “The place is imbued with the spark,” said my friend Francie. “It’s a special place… you’ll be impressed.”

I rolled through the gate of the well-maintained old house, pausing in the garden to savor a flawless live rendition of Bach’s sonata for flute unaccompanied. The performer was a gentle bearded fellow standing in an acoustically bright drawing room, the waxed hardwood floor echoing as the dust in angled shafts of sunlight danced to his Baroque sound.

Everyone in the building was quick-witted and interesting, from the ex-junkie once busted for armed robbery to Ann, who had originally invited me to visit. She greeted me and began an animated discussion of management technology, alert features energized by a passion for knowledge. “Most people aren’t willing to view management as a science,” she said. “It’s like alchemy before it became chemistry.”

A sign on one door read NO MO’RON FOR PRESIDENT. There were three computer systems, one machine in the hall slowly cranking out name tags for an upcoming poets’ conference.

Francie arrived. “What did you learn today?” was her first question, and I related my delight at discovering the dynamic families of the co-op world. I was sensing a higher level of maturity than I normally see in student communities — a sense of responsibility. People contribute to maintenance, meal preparation, and the self-government that keeps things running smoothly. Applicants are interviewed by the entire membership, for everyone has a stake in the ongoing quality of life.

The thing that makes this kind of structure successful, however, is the small size. People can intellectually grasp the entire organization; they can see the effects of their own activities on the whole. It’s socialism on a small scale, with little motivation for personal power struggles.

The only problem with the Whitehall was that I was staying in the room of a woman who was out of town for the weekend. So I moved to the Ark. This iconic co-op of a hundred rooms became my Austin base camp, a place to unpack at last and get to work.

Architecturally, the Ark had a pair of two-story wings flanking a swimming pool, with a large common area in the middle. I sensed the effect of building design on the residents’ psychology: everyone has to pass through the common area and eat there, giving the place a feeling of community that emerges in a playful, party-like atmosphere.

Again I had to be accepted for temporary residence. I was handled as any other applicant — fed, introduced around, then examined by a committee.

A couple of others were first. Their applications were read out loud, then they were questioned, asked to leave the room, and discussed with the kind of candor that comes from a desire to keep the neighborhood a happy place.

“How are you planning on paying your rent?” someone asked a rough-looking applicant. The answer was defensive, and the guy was rejected. “He’s not Ark material. Will one of you people who voted against him please go tell him?”

“Do you feel that Ford was within his rights when he pardoned Nixon?” someone asked the next guy.

“Well, maybe, but I really think he should have gotten rid of the WIN buttons!” The tall, shy advertising major was accepted enthusiastically.

At last it was my turn. I did a short monologue about the journey, requesting the unusual privilege of staying a short time without having to pay a deposit. “What about food?” asked an Indian named Mobishar.

“Oh, I do expect to pay… well, actually, I’m just a high-tech drag worm…” Laughter. I was in.

An argument broke out over points of order, growing louder as Mobishar claimed the floor and everyone shouted at him to shut up. Someone finally dashed across the room to smother him with a towel. “That’s not procedure, man!” he cried in a muffled voice.

So now I had an Austin home, a poolside room with bed and desk.

I felt like a student; during the first evening I became immersed in discussion of artificial intelligence, the new computer co-op, and the social significance of this place. There was no dorm-like sense of homogeneity — the Ark housed all backgrounds and attitudes, giving it a cosmopolitan flavor.

I wandered out to the pool one sunny afternoon and sat, writing, as two women floating in the water exchanged snippets of country and western songs. “You remember this one?” one would say, and then cut loose with sailing voice, vibrato and twang echoing from concrete walls around us.

A blind and mostly deaf man sat amidst the youthful blossoms in his dark world, feet moving to an internal rhythm. He was alone and thoughtful, then leaned forward suddenly and turned up his hearing aid to catch the strains of an old country melody wafting across the water. I tapped the keys; wind rustled the trees. A female laugh danced across the water, and the blind man smiled.

“The Ark is a synonym for procrastination,” someone told me, describing week-long parties and people dropping out of school to stay on at the co-op. “This place is a full-time job.”

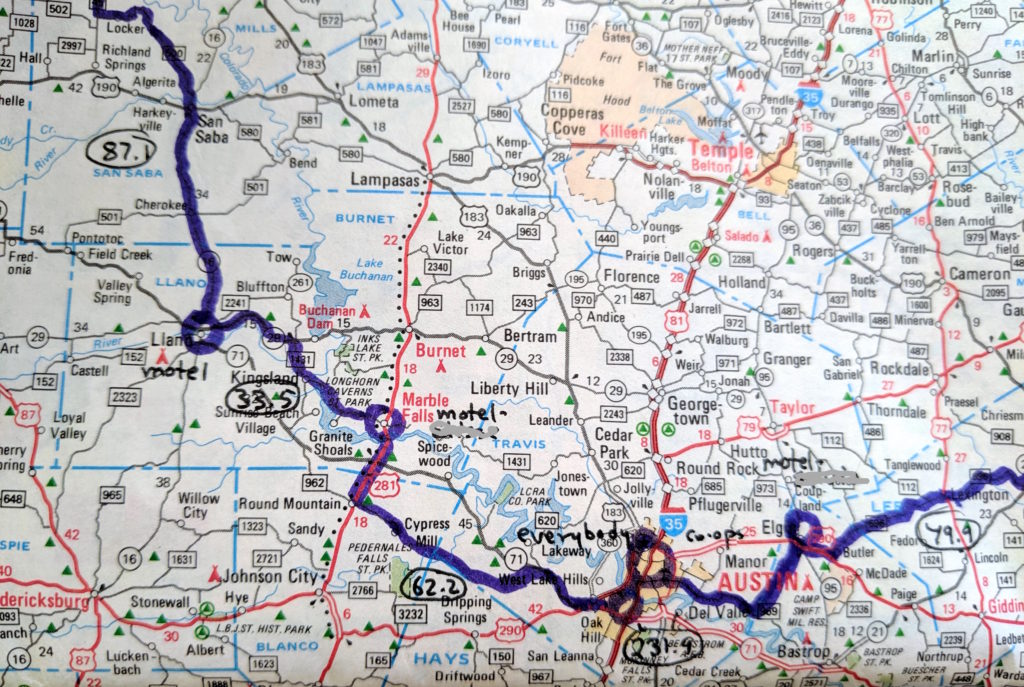

I rode 231 miles around town in the month I stood still, most of them on the exquisitely designed system of bicycle paths. The network is so complex that a colorful “Austin Bikeways” map is necessary to take full advantage of it, and I started ticking off routes as I had back in central Ohio, on a mission to cover them all before pedaling West Texas in July. I interviewed Joe Ely about his use of computers in music production, put faces to a few handles on CompuServe CB, sketched notes about this book, and caught up on freelance assignments.

At Lake Travis one night, I sat at a bar called “Drop Anchor” while the Whizz Brothers played blues/country/rock — staggering swaggering drunks in cowboy hats, the crack of billiards, rough conversation at the bar, and five little girls about ten years old incongruously clustered around my table. “I know you!” one cried. “I did a report on you in school!”

Bob Steele, the musician who had brought me there in the Steele Mobile, wandered by with a grin. “Well, I see you got your entourage.”

The journey was starting to feel like an abstraction after such a long layover, but the media machine was humming, enticing visions of a better-integrated bicycle were dancing in my head, the book project was on my mind, and my tires itched. It was time to get back on the road… this time with a companion.