Bicycle in Dataspace – Discover Magazine

This one was a hoot, and really captured the buzz of the developing BEHEMOTH project at the Bikelab hosted by Sun Microsystems (in building MTV4). The photo session was amusing… that big green shot spanning the first two pages was a complex setup by Christopher Gardner, with a smoke machine and fancy lights all arrayed in the lawn outside my Sun building. At about midnight, while we were playing with lasers and other variations, we were suddenly beset by a gawd-awful hissing on all sides: the Sprinkler System from Hell! The bike’s console was by no means waterproof yet, and I called for help… but the guys were much more interested in saving the Hasselblad. Harumph.

My mother loved this beautifully written article by Carl Zimmer, but was horrified by the magazine cover. This was also translated into Finnish, and ran in Tekniikan Maailma with the date 18/1991 (see images after the English Version).

Bicycle in Dataspace

Bicycle in Dataspace

by Carl Zimmer

Discover Magazine

July, 1991

Steven Roberts never fit in with his neighbors in the suburbs. The long road out led ultimately to Behemoth.

Some weird business is going on in the back of Building Four at Sun Microsystems — weird even for California’s Silicon Valley. Past the bland, cheerful lobby, past the huge storage area where two employees are playing field hockey among empty shells of old computers there’s a door with a sign that reads NOMADIC RESEARCH LABS.

The “labs” are really just a single room filled with equipment: computers, machine-shop tools, boxes full of ragged road maps, flutes, a wooden recorder. In the middle of it all sits what looks like the mutant spawn of a bicycle crossed with a computer. Roughly speaking, that’s what it is — a fully self-sufficient, solar-powered bicycle incorporating the most advanced computer technology available — and it answers to the name Behemoth.

Its maker, 38-year-old Steven K. Roberts, shuffles barefoot around his lab wearing gray sweats and a T-shirt. Roberts has traveled more than 16,000 miles in the past eight years on predecessors of Behemoth. It’s safe to say that during that time he’s led a highly atypical existence. Mounted on Behemoth, he’s a state-of-the-art, self-propelled nomad. He wanders as he pleases, yet he’s completely immersed in the ebb and flow of global information. “It doesn’t matter where I live now,” he says, “since I live in Dataspace. That’s my hometown.”

In the early eighties Roberts had a comfortable life in a suburb of Columbus, Ohio, working as a computer consultant and writing books with sober titles like Industrial Design with Microcomputers. But Columbus, as he puts it, “inspires long-distance travel.” One day, after realizing that the excitement he had once felt for his work was gone, he wrote down his passions: travel; bicycles; messing with computers; conversing with people via ham radio and computer networks; romance. He then tried to think of how he could satisfy them all.

His solution was to build a bicycle that could accommodate a computer, a citizens band radio, a ham radio, and solar panels to power them. The vehicle was a recumbent bicycle — the long, low kind in which the rider leans back as if in an armchair. The computer he chose was a laptop — at the time still a startling oddity. In the summer of 1983 Roberts put his house up for sale and set off. He cruised 70 miles the first day.

As he wandered across the country, he wrote articles for newspapers and trade publications such as Online Today, typing them on his laptop when he wasn’t riding and sending them over pay phones. Often he camped in a tent. For social contact on the lonely road, he would “talk” to people on computer networks.

He soon found, however, that life on the road needn’t be all that lonely. In his book Computing Across America, Roberts isn’t at all shy about describing how his bicycle, a great door-opener, led him into some torrid relationships. In fact, Roberts isn’t shy about anything. As he shows photographs from the road, he says, “That’s me on top of Clouds Rest in Yosemite.” It’s a naked figure on a mountain, back to the camera. “When you get to a place like that you’ve got to get rid of clothes. I know it sounds weird, but when the world’s at your feet you just want to feel like an animal.”

Musings such as these led Roberts to start his own magazine, The Journal of High-Tech Nomadness, in 1987. It’s a funky blend of travel notes, meditations on life, esoteric technical information, and the occasional chicken recipe. Roberts writes, edits, and even designs some of each issue on the road, then beams it to a desktop publisher in Minnesota who produces it and sends it out.

Roberts’s ability to do all this was largely the result of improvements he had made to the bike the year before, when he figured out how to type while riding. “I was in western Texas, with chapters of my book writing themselves in my head as I rode and then floating away. I play the flute, and I can get three octaves out of eight fingers with that, so I thought, Why not use the idea for typing?”

He installed four buttons on each handlebar and built in a computer above his front wheel. By pressing different combinations of the buttons while steering, he could manage a sort of stenographer’s script that the computer translated into English and displayed on a screen in front of him. “Riding and writing occupy different parts of my brain,” he says. “It’s like walking while having a conversation.”

Over the years of his wandering Roberts would update his equipment when he got the chance. It helped that he developed an affable relationship with big computer companies. When he heard about a new Hewlett Packard laptop that made his old one look like a Univac, for example, he was able to talk the company into giving him one. “I tell companies that in return for their machine I give them engineering feedback. And they also get a lot of PR in the process.” It’s a nice arrangement all around — so nice, in fact, that more than 140 companies have given Roberts equipment.

But by 1989 it had become clear that if he wanted to stay on top of his unique profession, he would have to make an extended stop for a major redesign. After a year of making do in odd spaces like a school bus and a table-tennis room, Roberts was given some rent-free space at Sun Microsystems this past August. Now, almost a year later, Behemoth (which stands for Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine … Only Too Heavy) is almost ready. Roberts has been working in the lab around the clock for the past few months; he will resume riding this month.

The skeleton of Behemoth is the bike itself, which Roberts has rebuilt to handle its 350-pound load; roughly half this weight is carried on the bike and half in a trailer attachment. The bike used to have 54 gears, but now it’s up to 105. In low gear Roberts has to pedal at 60 revolutions per minute to creep along at 1.2 miles an hour. While that may be good for climbing mountains, it’s hard to balance such a heavy bike at that pace. To compensate, Roberts is adding training wheels that will extend like landing gear when he squeezes a handle.

All of Roberts’s equipment fits into three places. A curved white hood sits above the bike’s front wheel with an aircraft-like console that faces the rider. A large compartment called the Rump (Rear Unit of Many Purposes) is behind the seat. And a big yellow trailer is hitched in back.

Behemoth gets electric power from a panel of photovoltaic cells stretching across the lid of the trailer. These dump 72 watts of captured solar energy into batteries underneath, where a computer manages the flow of current to different pieces of hardware. Any extra juice gets sent to the refrigerator on the Rump, where Roberts keeps grub and drink. He is so obsessed with harnessing every bit of energy that he even gets power from braking. Using normal friction brakes, you slow down by converting the energy of your motion into wasted heat. Roberts installed electric brakes — basically, they convert the energy of motion to electric current, which Roberts can then shunt to the batteries or the refrigerator. (This was never finished. -SKR)

Much of the computing equipment that thrives on this power is under the hood. The console contains three screens, run by separate computers. Roberts uses a Macintosh screen for everything from word processing to checking the power supply. Below it is a narrow Toshiba screen that he prefers for bike maintenance and diagnostics. Roberts can flip the Mac screen up to reveal another monitor — this one a high-resolution DOS VGA screen that lets him do circuit designs and other tasks that need good graphics.

The hood opens like a lotus flower, revealing a dozen circuit boards shoehorned into every square inch. In the midst of it all is a board called the Bicycle Control Processor — the bike’s nervous system. “The BCP takes care of network management,” says Roberts. “It’s the guy at the hub who’s throwing lots of switches.” Distributed all over the bike, he says, including the trailer, “there are many other computers that are much, much smarter than that.” While all these computers might seem redundant, they actually save electricity. The alternative to using one small computer at a time for specialized tasks would be keeping a big, thirsty computer turned on all the time.

Roberts put this decentralized strategy to good use when he recently honed his word processing system so that he can type more than 100 words a minute. He describes the process at breakneck speed, forefinger flicking around from circuit boards to screens. “Under the handlebars there’s a little microprocessor whose whole job is to encapsulate the combinations of keystrokes. It sends them to the Bicycle Control Processor, which turns them into something that looks like regular keyboard typing. It passes them to the Toshiba, which is running a program that lets you use macro codes.” Macros are abbreviations for frequently used phrases, such as “otr” for “on the road”; the Toshiba expands these notations automatically. “It squirts the data out, which is now moving very fast, to the BCP, which sends it over to the Mac screen, which sees this hundred-word-a-minute typist wailing away.”

Roberts has gotten rid of the citizens band radio, but he’s added a cellular phone; he may also add an answering machine. And his computer can now ship and receive faxes. To link with other computers, he can dial a commercial network on his phone if he’s within 100 miles of a city or use a satellite terminal — a transmitter-receiver in a foot-wide dome that hangs off the end of the trailer — to enter the global network known as Internet. And he still carries a laptop on the Rump. “I can unplug this,” he says, raising the metal briefcase cover, “and take it with me. It has a radio link back to the bike, so anything I can do on the bike I can do from three miles away.”

Roberts is not about to fumble with a radio or telephone as he rides along. He built all the communications electronics into the trailer’s “equipment bay,” and he can use voice-recognition and speech-synthesis software to run it.

A typical scene from his upcoming travels might go like this: Pedaling along through the Pacific Northwest, say, Roberts listens to music piped into his earphones. He decides to ask a friend he’ll be staying with for directions, so he says, “Behemoth.” The bike responds, “Yes, Steve.” Roberts says, “Dial this number,” which he’s called up on-screen from his data base; the computer puts the call through to Roberts’s left ear. All of that may be a significant power drain if it’s a cloudy day, so as he talks, a low rumbling voice — the trailer might deliver a warning in the other ear: “Power is twenty-five percent.” Meanwhile Behemoth has fired up the satellite terminal, collected and sent Internet mail, and shut the terminal back down. When Roberts is done talking, Behemoth says, “You have two pieces of mail, Steve.” And when Roberts says, “Read mail,” the computer converts the text into speech.

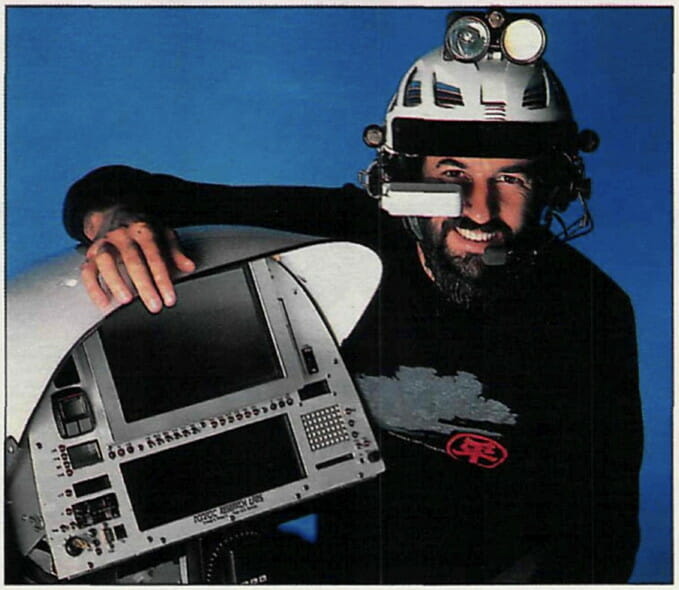

Behemoth can recognize only a few hundred words, so Roberts can’t do everything he’d like just by talking. He also uses a sort of head-mounted mouse to control a cursor on the Mac screen: three ultrasonic sensors on his helmet move the cursor around according to the movements of his head, “as if it were tied to the end of my nose.”

Roberts has a knack for combining hardware and software in ways rarely seen outside the military. Take, for example, his satellite navigation system. More than a dozen Global Positioning System satellites send out signals that can be used to determine latitude, longitude, and elevation to within a hundred feet. Roberts will tap into this system using an antenna that looks like a bulging white tile on the hood. He also has maps of-the United States on compact disc and an electronic compass. Through software he wrote to combine these three resources, he’ll conjure up a moving map on his screen pn which he is a blinking arrow.

But even that’s too primitive for Roberts; he’s now turning the system into a cyclist’s dream. “I want to take the topographical information and pass it into a drafting program that could generate wire-frame models of the landscape, so I could say, ‘Behemoth, show me the next fifty miles from two miles above my present position,’ and see how hilly the roads are. This stuff is serious black magic.”

All this expensive equipment, not to mention the investment of loving labor, suggests the need for a staggering security system, and Behemoth doesn’t disappoint. A microwave proximity sensor on the Rump can be set to pick up anyone approaching within ten feet and trigger an alarm. If someone actually jostles the bike, a separate motion sensor, “a blob of mercury with a forty-kilohertz field around it,” feels the jolt. And just in case someone ignores the alarms and carts off the bike, Behemoth can transmit the change in its satellite coordinates.

Roberts can set the security system to work automatically, or he can intervene by remote control. “Depending on my paranoia index, I can pick the sensitivity I want,” he says. For instance, if he parks Behemoth in front of a diner, he doesn’t want to set off an alarm if someone merely passes by. But if someone touches Behemoth, that might trigger a conventional car siren or a cacophony of synthesized sounds. If Roberts wants to intervene, the system contacts him via a hand-held pager, and he can pick his response while listening to what’s going on through a sort of wireless intercom. He can then have the speech synthesizer say something appropriate to the occasion, like “Do not touch, or you will be vaporized by a laser beam.”

If someone is really bent on doing harm, Behemoth can dial 911 and deliver a message: “Hello, police, I am a bicycle. I am being stolen. My current latitude is…” If a thief persists, the electric brake on the front wheel can be activated, resisting motion, and Roberts has contemplated putting an electrical stunning mechanism in the seat, although it’s doubtful he’ll go that far.

He’s done it before, though; in some ways Roberts hasn’t changed at all from the engineering fiend he was as a child in Louisville, Kentucky. “I always had trouble with the neighborhood kids,” he says, “because I was this weird techie who liked electronics and they all liked baseball and wrestling. So one day they roughed me up on my way home from school. They doused me with squirt guns and got my books wet. It was very humiliating.

“I had just read an article about this thing called the Tickle Stick. Basically it was like a cattle prod that runs on a couple batteries. So I built one. I took two squirt guns and mounted them on a little wooden stop with a handle that would squirt them both in parallel streams. I put salt water in them, which is conductive, and connected the terminals of the tickle stick to the brass nozzles on the squirt guns. So as long as both streams touched somebody without breaking into drops, they’d get a shock. I hung this thing on my bicycle, scared to death, and cruised down the street where these punks lived, my heart pounding.

“They came out saying, ‘Get Roberts!’ I grabbed the squirt gun and squeezed blindly. I was so afraid I was going to get murdered. It was incredible. Kids were falling off their bicycles and writhing in total shock, psychologically as well as electrically. I ran out of water and got on my bike and hightailed it for home, where I hid in the basement for a while thinking they’d come for me. They never did.”

Generally Roberts is far more comfortable with a less physical means of persuasion: he sings the praises of networks, not weaponry. “You give some fourteen-year-old in Podunk a computer on a network, and he’s no longer the same kid; he’s out in the world, and the only thing that matters is his brain. It’s a great equalizer.”

Sun Microsystems likes to have this kind of mind in-house. If there was ever a poet in residence at a computer company, it’s Roberts. Every Friday people come to his lab to look at the latest improvements on his bike and make suggestions. For his part, Roberts gives the company suggestions about how they might improve their products.

Sometimes the relentless evolution of computers gets to him. “I will look back on this in a couple years and think, ‘What a clueless guy. What a waste of material.’ It’s driving me crazy,” Roberts says, opening the console. “Here are the hard disk drives, which I put in a year ago, with forty megabytes of memory each. It was very exciting at the time.” He points out two cartridges on a panel of the console, the size of Tolstoy paperbacks. “Well, forty-megabyte drives today are this big,” he says, picking up a cartridge smaller than a deck of cards from a worktable. He scowls at the obese drives for a few seconds and then says, “I think I’m going to replace the whole thing. I can get seven of these in there instead of two.”

It’s going to be another late night in the back of Building Four.

Carl Zimmer has written a number of excellent books on scientific subjects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.