Beyond Mobility – Mobile Office

I’ve always liked this article – it’s well-written and takes the long view. Penned by Dan Rosenbaum from the perspective of the nascent personal mobility industry, it catches me during the very early years of the Microship project… and he’s still at it, writing about new media as it continues to unfold.

by Daniel J. Rosenbaum

Mobile Office

March, 1995

How a “technomad”

extended the scope of

mobile computing

just for the hack of all.

Progress is made by people who take what exists and advance it one step further. Consider, for instance, the person who first strapped an engine to a horse-drawn carriage. Or the individual who looked at a radio and a telephone, and wondered why the former couldn’t be designed to work like the latter. Or the people who decided that a personal computer could be shrunk to a size that enabled users to carry it from room to room.

There’s someone who has taken all this one step further: Meet Steve Roberts, technomad. Roberts has taken “mobility” the extra steps to “nomadness,” shedding almost all attachments to a home base and relying as much as possible on the powers of muscle, brain, and technology.

Roberts is best known as the guy who sold his house, built a recumbent bicycle with more technology aboard than most midsized companies own and set out on the open road. Crazy? Well, let’s say that it’s not a life that most people would choose. But as an experiment in mobility, technology, and psychology, Roberts and his work demands attention.

“Technomad” is a label that suits him well, the word being more complicated than it first appears. Read it as “tech nomad” and you have a picture of someone who takes up residence on the road, encased in a cocoon of technology. Read it as “techno-mad,” and you have an image of a wild-haired programmer, sitting in a lab until 3 a.m. coding away on control systems, pushing the limits of technology just for the sake of doing so.

Both readings of the word (and of the person) pretty much fit. Roberts is a rangy 6-foot-4-inch man with a quick smile and a body that appears to be composed exclusively of slow-twitch muscle. In person and through E-mail he attracts an ever-changing cloud of people with whom he shares ideas, some of which are brilliantly clear, others close to the fringe.

Roberts’ first expedition started in 1983 when he created the Winnebiko, essentially a recumbent bike outfitted with a Radio Shack Model 100 laptop computer and solar panels. Two years and 10,000 miles later, he took a break to build the Winnebiko II. The bike and laptop mushroomed into 54-speed recumbent cycle with five computers, three ham radio stations, packet data communications, 108 square feet of tent space, a remote-control paging security system, a 3.5-inch disk drive, three modems, a speech synthesizer, disc brakes, a TV set, and a microfiche documentation library. The entire contraption, trailer included, weighed 275 pounds.

So how could you actually do any work while pedaling? Roberts built eight buttons into the bike’s handlebars, four on each side, resting under the fingers. With surprisingly little training, it’s possible to type by pressing the buttons corresponding to a character’s ASCII code. It’s neat, but not for everyone.

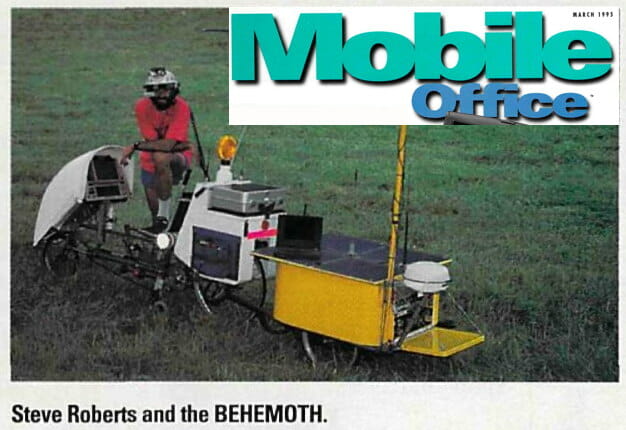

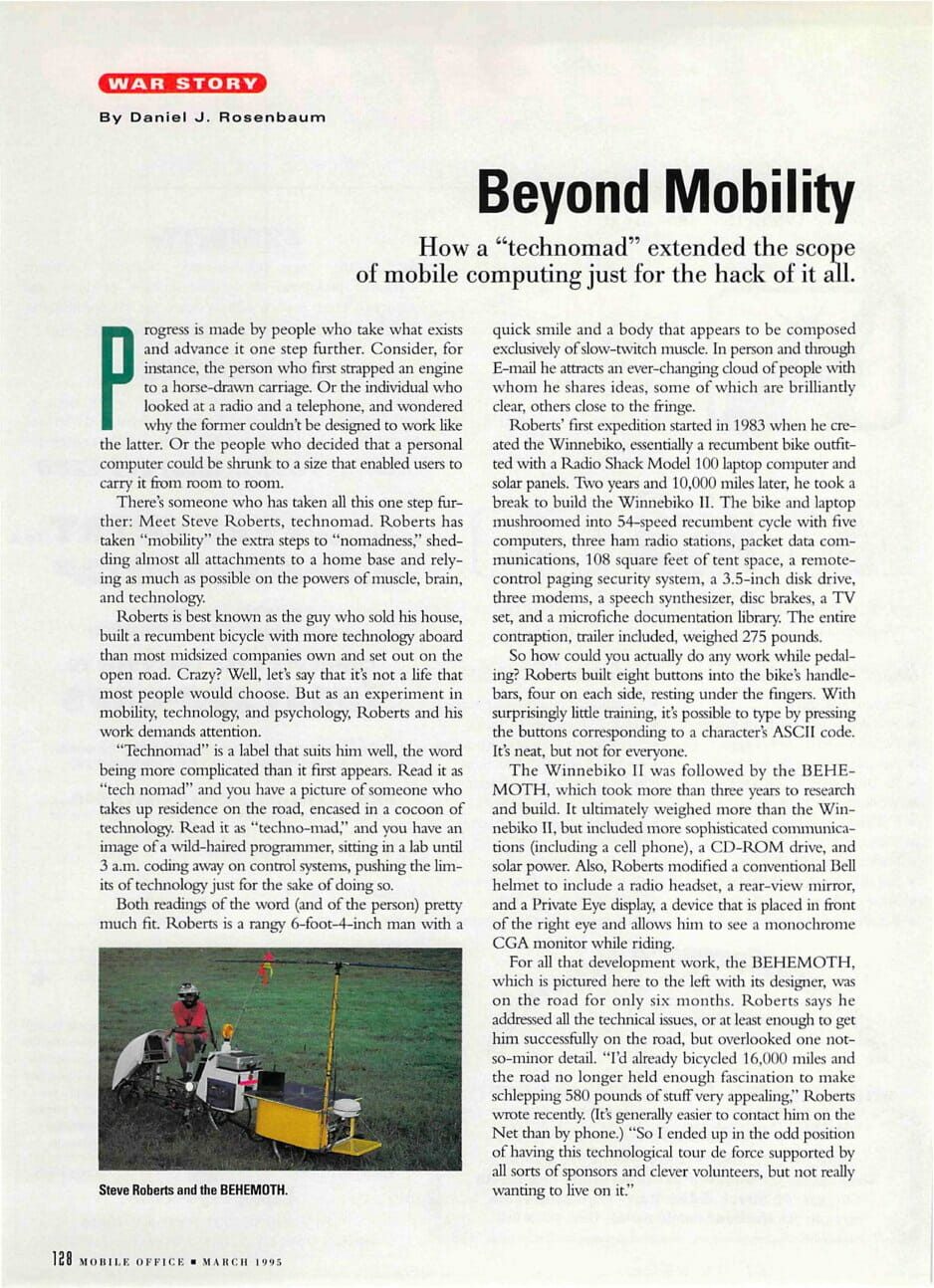

The Winnebiko II was followed by the BEHEMOTH, which took more than three years to research and build. It ultimately weighed more than the Winnebiko II, but included more sophisticated communications (including a cell phone), a CD-ROM drive, and solar power. Also, Roberts modified a conventional Bell helmet to include a radio headset, a rear-view mirror, and a Private Eye display, a device that is placed in front of the right eye and allows him to see a monochrome CGA monitor while riding.

For all that development work, the BEHEMOTH, which is pictured here with its designer, was on the road for only six months. Roberts says he addressed all the technical issues, or at least enough to get him successfully on the road, but overlooked one not-so-minor detail. “I’d already bicycled 16,000 miles and the road no longer held enough fascination to make schlepping 580 pounds of stuff very appealing,” Roberts wrote recently. (It’s generally easier to contact him on the Net than by phone.) “So I ended up in the odd position of having this technological tour de force supported by all sorts of sponsors and clever volunteers, but not really wanting to live on it.”

Instead, he felt the tug toward water, which led to the conception of the Microship, a human-powered, technologically mobile boat. The idea was born in 1991, but the first test sailing didn’t take place until late 1994. It was not a terrific experience. A two-week run from Seattle was, judging from Roberts’ report, a harrowing ordeal that included strong currents, unexpected obstacles, and less-than-ideal landings. The electronics worked fine, although not much else did. So Roberts went back to the drawing board to retrench and to rethink, and it’s not clear when the next version of the boat will sail.

Helping Roberts think through the technological and lifestyle issues is a team of about 400 people on the Internet’s Technomads mailing list, as well as a long list of sponsors and a partner, Faun Skyles. Anyone with E-mail access can subscribe to Roberts’ mailing list by sending E-mail to [redacted]. Leave the subject line blank and enter “add address nomadness” in the message body. (Of course, send it without quotes and substitute your E-mail address where appropriate.) Those with a Web browser can point it to https://microship.com (updated).

Why does he do it? What keeps him going now is the hack in its purest form, the sense that adventure and discovery are where you find them. “Whoever you are, if you’re interested in being a technomad, focus on your system and make it … suited to your needs, your budget, and your travel fantasies,” Roberts writes. “The bottom line is having an interesting life filled with learning and adventure, and that means something a little different to every one of us.

“I’ve seen so many people look back over the decades with a vague sense of having missed something and the depressed realization that it’s too late to start anything new,” he says. “I want to feel that I’ve lived as fully and had as much excitement as possible. I may have a few regrets about wrong turns and wasted time, but mostly I feel that I’ve fulfilled this. And I intend to keep doing so!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.