Landing Gear Steering and Deployment

By mid-1999, the new lab on Camano Island was in full swing, and we were audaciously publishing expedition plans. One little snag, though… the landing gear project was turning out to be far more complex than anticipated. Here we discover, with a vague sense of horror, that the Microship would need a custom hydraulic Ackerman-steering system.

Microship Status Report #130

by Steven K. Roberts

Camano Island, Washington

June 21, 1999

“Exhilaration is that feeling you get just after a great idea hits you, and just before you realize what’s wrong with it.”

– Rex Harrison

The North American Microship Expedition

You know, I really need a name for this upcoming technomadic adventure… I was doing an interview with Jeff Blumenfeld of Expedition News last month, and he wanted to know what we’re calling our little computerized amphibian trimaran outing. “You need a NAME,” he said. That seems like a good working acronym… how about the North American Microship Expedition? <grin> If we do it a Second time, I guess it would be the SAME. But the Last one will sound terrible…

It was going to be just “American,” but recent events have added a high-adventure twist to this whole affair…

We’re currently working out details having to do with such scary things as cranes and releases of liability, but if all goes as hoped, we’ll roll the boats down the driveway next May 20. Launching a mile from here, we’ll sail away from Camano Island on a 5-day shakedown loop in local waters. This will be our last chance to “get it right,” for after a quick stop at the lab we’ll sail up to Vancouver, BC, fly the boats through the air via crane ‘n sling onto the foredeck of a grand Holland America cruise ship, then steam up to Glacier Bay, Alaska, as part of the Perl Whirl. Yep, this is a whole cruise devoted to the Perl language, with a shipload of gurus giving technical presentations while the dazzling beauty of the British Columbia coast drifts by. Enroute, we’ll demo Microship systems and hang out with the wizards, no doubt cranking out some last-minute scripts with their help if our normal PFD mode (Procrastination Followed by Despair) continues unabated.

Instead of returning with the cruise to Vancouver, however, we’ll jump ship in Ketchikan… slinging our tiny boatlets once again through the brisk northern air and onto the docks just north of the infamous Dixon Entrance, where the exposed Pacific often lashes the coast with 15-foot seas and gale force winds. During a weather window, we’ll haul ass wide-eyed across that little trial by fire, then continue south through the Inside Passage.

Some 700 miles later we’ll re-enter our home waters, pause briefly for a game of volleyball and a few days of battle-scar repair, then continue south: upstream southwest of Olympia, overland with our magic landing gear to a creek that dumps into the Chehalis, downstream to Gray’s Harbor, then over more backwaters and portages to Willapa Bay and thence to the mouth of the Columbia River inside the Bar at Ilwaco. From there, we’ll plod 465 miles upriver on the Columbia and the Snake to Lewiston, Idaho, then truck the boats over the mountains to our originally planned starting point at Three Forks, Montana — the headwaters of the Missouri. From there, it’s only another 12,000 miles…

This succession of portages (not to mention daily haulouts for camping and visiting) would be impossible were it not for the landing gear, the integration of which was anticipated back in Issue #122 when I footnoted announcement of the new Seitech wheels with this casual comment: “All we need is a hinged strut assembly and associated control lines, and she’s ready to roll.” Bob spotted that line in a TAPR Packet Status Register reprint of the 12/97 article the other night, and began chasing me around the lab in mock fury… for this has not been an easy road. It’s not over yet.

The Landing Gear Ordeal

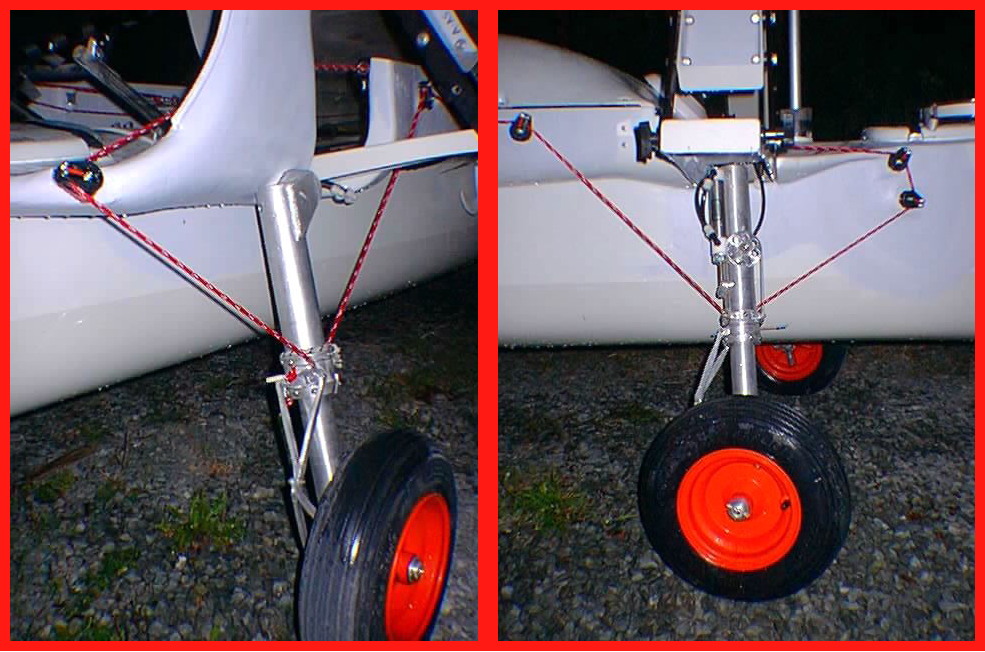

Yes, our innocent little “oh, and by the way, the boat needs wheels” comment has turned into a monstrous engineering project. In our last update, 2 months ago, we had chased down most of the aluminum tubing and Bob was sawing precision jigs for the welder. Today, the boat is resting on her landing gear, though the temporary lashup still depends upon carefully strung line with Spanish Windlasses maintaining proper deployment angles

Getting to this point has surpassed the fabrication of the boat itself in complexity (now I know why this has never been done). We were lucky to find Dennis (The TIG Shop) and machinist Dan Dodge, both here on Camano Island; McMaster-Carr has become such a familiar industrial supply resource that after years of trying we’ve qualified for the coveted 3,000-page catalog.

Our aluminum tubing haul from Metalshorts has now been turned into four sets of struts, with beefy axles supporting the wheels. The struts consist of two concentric tubes and an inner guide to support the Miner Elastomer shock-absorbing bumpers… with Delrin rings and aluminum stops defining the limits of travel. At the top of each strut, a large tube is welded parallel to the ground, and these rotate within molded fiberglass nests with Teflon collars glassed into the boat. The assemblies are retained to allow free rotation without falling out… and the front pair terminate in exquisitely lathe-turned sealed bearing assemblies (needle and tapered-roller) to allow castering while underway. In addition to designer Bob Stuart, thanks go to Paul Elkins for tubing cutting, as well as Drew Carlson and Charlie Nystrom for a full day of fiberglass layup where the landing gear meet the hull.

Bob rigged temporary spacers to lock the struts to full extension and assembled the four units, noting with relief that they retract properly into the space under the solar panels without crashing into anything (very tricky geometry). We lashed them into position and began the long process of staring at them, trying to figure out how our vague “lines and cleats” notion could be applied to effect deployment and retraction from the cockpit, including the critical rotation of the wheels themselves. I should note here that the 8″ suspension travel complicates things by precluding direct connection to the axle assemblies… angular control has to be remotely managed through “scissors” hinged to collars rotating on the upper struts.

It took a couple of days of hard noodling, but we now have a deployment design — the landing gear can be managed by a pair of levers on each side, one handling uphaul of both fore and aft units and the other doing the downhaul along with invoking hydraulic rotation (the geometry wouldn’t allow a single lever for all this, alas — the lines move at different rates and would either go slack or lock up in the transition zone). It takes 8 Ronstan turning blocks per side, along with a few other tricks, to handle the line routing… and it looks like everything is far enough above waterline to eliminate fair-weather splashing.

But a problem lurked in the steering geometry, and it became painfully obvious the first time we nudged the boat backwards. Because of the non-vertical steering axis imposed by retractability, castering was a mess when not rolling forward… the wheels flopped over to a nasty angle and set themselves up for serious side loading.

Uh-oh… come back here, Bob! The boat needs active steering!

This is a mixed blessing: while imposing another engineering nightmare on our critical path, it solves other problems — including concern about where, exactly, free-castering front wheels would point when we hit the beach. Each front wheel strut will now carry a Clippard cylinder with 3″ travel, linked to the “steering collar” via a belt and some machined pulleys. The cylinder’s position is the resultant of three controlling influences:

- A covered “hydraulics pod” on the bow accepts a lightweight 10″ winch handle, allowing me to actively steer while I’m harnessed up and dragging the ship down the street. Bob quite outdid himself with this design, implementing 110 degree lock-to-lock Ackerman geometry using a swiss-cheesed cam-follower driving one side and a direct linkage for the other. This minimizes tire scrubbing by steering the “inside wheel” on a turn more sharply than the outside, as in almost all automobiles and even some better engineered recumbent trikes.

- If we assume that the steering cylinders at the bow are locked in a neutral position, then we can actively rotate the front wheels 75 degrees into correct alignment during their descent by simply adding two more cylinders, linked to the deployment levers. This is starting to look like a jet fighter…

- The nasty problem of implementing useful brakes that survive saltwater immersion can be solved with the hydraulic equivalent of software by entering “pigeon-toed” mode… pulling yet another lever at the bow while steering hard left rotates both wheels 45 degrees inward. Trying to stop with this method while careening downhill would introduce catastrophic stresses, but as a parking and hill-holding brake (our primary need) it’s perfect… though it might look a bit weird.

All this translates into a lot more fabrication before we put the landing gear behind us. I drew the entire hydraulic system as a two-page CAD file, bought $450 worth of plastic fittings and Nylon-11 tubing from McMaster-Carr (about the same price as Lisa’s new 1985 Chevy Sprint, fittingly named McMaster), bought plastic stopcocks from Cole-Parmer for the 10-channel pressurized hydraulic recharge manifold on the aft bulkhead, and spec’d the nine additional Clippard noncorroding cylinders needed in addition to the four already in use as rudder controls.

This is getting to be one VERY strange looking canoe…

Other Microship Developments

Meanwhile…

I’ve made progress on the hydraulic control pods, molding the first of the “armrests” with 4 layers of 10-ounce cloth, assembling stainless drawer slides to the mounting base, and coupling the two via a milled-out end plate bolted to the armrest and capturing the cylinder’s rod with acorn and jam nuts. I’m still unsure of the human-interface module and how it will connect to the console (IrDA or wire), so I’m leaving room for cable just in case I have to do it the messy way. I also added a stopcock to the design so the helm can be locked… it’s no substitute for an autopilot, but easy to implement (and useful for security). But I’m tempted to drop in my old Navico tillerpilot driving another hydraulic cylinder as the shortest path to self-steering… now that I know what pumps and valves cost, rolling my own under control of a FORTH task is less appealing.

And reminiscent of Ettore Bugatti’s comment in response to a customer complaint about the brakes (“I make my cars to go, not to stop!“), we have finally solved the anchor problem. A 9-pound Delta is bungeed into a slot on the forward aka, starboard side… adjacent to a chain bin and cleat. The Ankarolina, a 185′ reel of flat nylon webbing, is bolted to the forward hatch cover. I had planned to deploy the anchor via a bridle between the ama bows to avoid the classic multihull “sailing back and forth at anchor” problem, but we’re going to try a simple approach — cleating the line about 2 feet off centerline and just letting her look funny. With nonskid paint on the bottom of the folded inner solar panels, and glow-in-the-dark nonskid tape on an inset footrest on the cowling, I’ll tether myself, clamber forward, unbungee the anchor, toss it and 10 feet of chain overboard, then pay out webbing until we’ve reached adequate scope… cleating it to the aka when done.

Speaking of deck fixtures, this mailing list has again revealed itself to be a near-infinite source of information… my IN-basket lit up with discussion about loading the rotating mast as an HF antenna after I raised the question in Issue #129. After lots of noodling, I concluded that yes, it’s technically possible in an ideal world, but no, in this corrosive dynamic environment it’s not practical… so I’ll mount a whip to the port arch vertical and load ‘er up conventionally. I’m now defining the other antenna locations, but will save that rap for another time.

In addition to the mast commentary, about a dozen people responded to my question about emulating a PC mouse on the Palm platform with pointers to two packages… many thanks for the input!

We haven’t started vacuum-bagging the solar panels yet even though the okoume skins and Divinycell foam core are sitting here gathering dust, but one HUGE design problem has been solved, thanks to our old friend Kevin Hardy who sent the perfect SeaCon wet-pluggable 4-pin connectors. Each boat will carry four bi-fold panels of four Solarex 30-watt PV modules each… and these connectors will let us treat the whole array as eight 60-watt channels to facilitate peak-power tracking and accommodation of partial shading — Tim Nolan, our power guru in Wisconsin, is testing PPT algorithms now and seeing 5-20% improvements over a direct solar-battery connection.

Bob did a brilliant “they said it couldn’t be done” bending job on a hunk of 7/8″, .120-wall aluminum tubing… forming it into a windshield frame with flattened mounting flanges that mate with molded nests on the cowling. This will carry tether eyebolts, a hinged 12×30″ piece of acrylic or polycarbonate, and act as the forward support for the retractable bimini (now being designed by Mary Davis and Lisa with Sunbrella fabric — red in my case to match the detailing on blocks, wheel hubs, valves, steering handle, and anchor). For ages we agonized over the addition of a windshield, assuming that it would require a wiper… crossing that invisible line between high weirdness and wretched excess. Fortunately, someone reminded me of Rain-X, so we’ve stepped back from the brink once again.

In what amounts to a HUGE architectural change in our embedded systems, we’ve decided to dedicate the existing FORTH hub to the ROM-based I/O management at which it excels, and do our server development and fancy stuff in a linux environment. Considerable research into the perfect platform at last yielded an amazing piece of hardware ideally suited to the task — the PC-500 from Octagon Systems. I’ll do a feature on this when we actually start working with it sometime in July, but basically it’s a 133 MHz PC on a 5.75 x 8″ card with 48 Meg of DRAM, on-board 10BaseT support, PC/104 stacking connector, 5 serial ports, 24 extra parallel bits in addition to a PC printer port, Disk-on-Chip socket, excellent power management, and interfaces for flat panels and hard disks galore. Our linux development team (Bdale Garbee, Matthew Hixson, Brian Willoughby, and Bill Vodall) will be working on the Debian GNU/Linux port, Microship interface daemon, Apache HTTP server, Perl scripts to link Mimsy pages with I/O events, local and global networking tools, sensor log database, telemetry scheduler, and on-board power-control hacks.

And while work on Delta continues apace, I’m happy to report that Wye has been dusted off and relieved of her duty as auxiliary workbench and storage unit. The sister ship is now two weeks into fabrication, and Lisa’s doing 100% of the work — arriving in the lab every day to slather epoxy, cut cloth, glue Divinycell, install hardware, and work on deck parts… coached carefully by Bob. This one should go relatively quickly, not only because the design is done and there’s a boatlet to clone, but because some of the nastiest layup jobs can be done BEFORE the deck is installed. Delta’s mast step, rudder hydraulic reinforcements, and battery floor were all installed via the boatbuilder’s equivalent of arthroscopic surgery… through hatches!

Lisa’s goal is to get the boat minimally seaworthy by the Sea Kayak Symposium in Port Townsend Sept 17-19, where all three of us are speaking this year. As in industry, it takes deadlines to wade through PERT charts… my next target date is the messabout of the Traditional Small Craft Association here on Camano Island on August 14-15. (This is rich with irony, but as the local TSCA folks put it, they have yet to agree on the definitions of “Traditional” and “Small” — so they’re letting me join!)

Casablanca, Marathons, and News

We drove to Colorado Springs in May to speak at a Quantum event, and are delighted to report that we now have an 18 gigabyte hard drive for the Draco Casablanca. The mind reels. Lisa is ecstatic. We headed up to Boulder to spend a few days visiting Draco, and came away with a real appreciation for the joys of a corporate culture defined by an intelligent and playful CEO. Yet another addition to the extremely short list of places I’d actually consider working… there’s even a company marimba band that rocks the house from the break room.

Anyway, the Cassie is a real success story — this standalone nonlinear digital video editing system is easy to use, conjures beautiful results, and offers a palette of effects and transitions that cover the range from subtle intonation to outrageous eye candy. With every project, Lisa ventures further into music synchronization, precise timing, and the kind of coherent overall feel you expect from a professional production… and she’s starting to see the “sister ship” more as a floating Casablanca substrate than mere solar microtrimaran. Our latest addition is a Heimdall DVD backup unit, so video projects in progress can be saved with no quality degradation.

The Draco visit was part of one of those marathon mothership adventures that both feed us and keep the moss off our toes, and this loop through the northwest states included some stunning country. Indelible in my memory is driving in a raging blizzard over Monida pass on I-15, listening to the growing hiss of corona across the whole HF spectrum, ending abruptly with a loud snap as lightning rips past our windshield to be followed about 300 milliseconds later by a thunderclap that dwarfed the growl of the diesel. I really expected our new G3 PowerBooks to be wiped clean by EMP, but they emerged from sleep without incident. Even Java the cat was wide-eyed at this storm, and she’s usually pretty blasé about what’s outside the truck until she recognizes the approach to Camano Island.

(And, purely as a recommendation for anyone who enjoys a good road, you MUST someday drive US 12 from Missoula to Lewiston. Trust me on this. Just do it. I dunno what it is about that number, but one of the other most stunning roads in the US is Route 12 in Utah…)

The journey was our usual jam-packed succession of interesting events, including a meeting at Qualcomm about Globalstar implementation on the Microship, a revealing linux platform discussion with Bdale Garbee, a visit to Octagon Systems, an evening in Moscow with Matt Hixson, and a blur of KOA’s and highways… all on the heels of another marathon with a different flavor:

Prompted by an order for 160 copies of our book about the succession of technomadic projects from Winnebiko to present day, and embarrassed by the badly out-of-date version we’ve been shipping, we decided a week before departure to crank out new edition of From BEHEMOTH to Microship. Barely leaving the waterbed for five days, we flailed away on our laptops — me writing and Lisa doing PageMaker — ending up with a 130MB folder containing a 100-page book. We convinced Pacific Copy in Everett to let us inject this directly into their ethernet, whereupon they printed it to the magic Docutech… a day later handing us a few boxes of staple-bound books. Amazing.

We’ve decided that publishing is essential to long-term survival, so I just ordered a block of ISBNs from Bowker (the key to being taken seriously by distributors). One of these days we’ll set up a secure server, but in the meantime, if you’re interested in any of our pubs, please drop me a line…

Speaking of keeping us in epoxy, thanks to Michael Tompkins for a spontaneous $35 donation to the project. We’re not a non-profit (except in a de facto sense) so this isn’t deductible, but I don’t discourage it! <grin>

We have two new media events since last time — an article in the May Expedition News and a cover story in Issue 4 of Recumbent UK.

And I just finished reading an awesome book — a pleasure at every level of magnification from grand concept to immediate textures and hilarious asides. This latest from Neal Stephenson is worthy of many superlatives (as are his others); by all means treat yourself to a week with Cryptonomicon.

And now, back to the lab!

You must be logged in to post a comment.