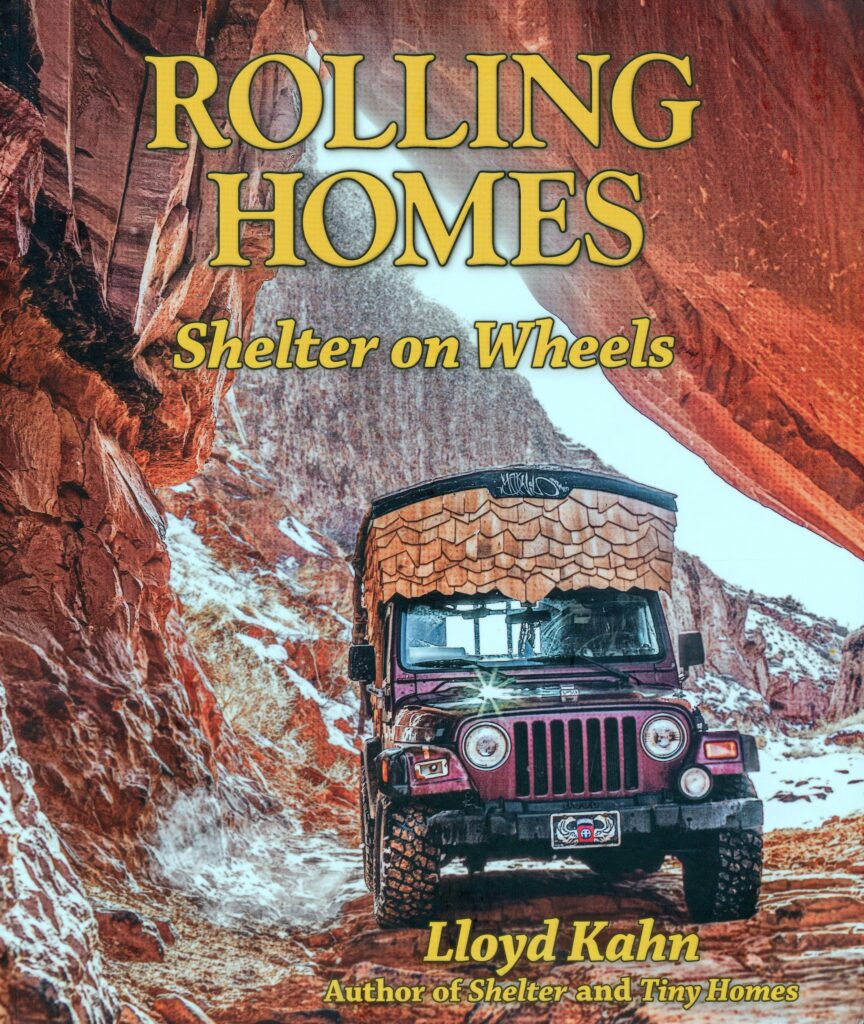

Winnebiko in Rolling Homes by Lloyd Kahn

Shelter Publications has been producing dreamy wish books of tiny homes and efficient nomadic tools since 1973, and if you have ever fantasized about taking off in a home on wheels, you almost certainly know his work. Rolling Homes is Lloyd Kahn’s latest volume, published in August 2022, and I am delighted that it includes four pages about the computerized recumbent bicycle on which I traveled 17,000 miles back in the 1980s. The book is a treasure, filled with marvelous machines and interesting people; you can order it here.

The pages shown below have different page numbers; this was the proof PDF and I don’t want to damage my copy of this beautiful book to scan it. The text is pulled directly from those pages for easier reading and searchability.

Introduction from Lloyd:

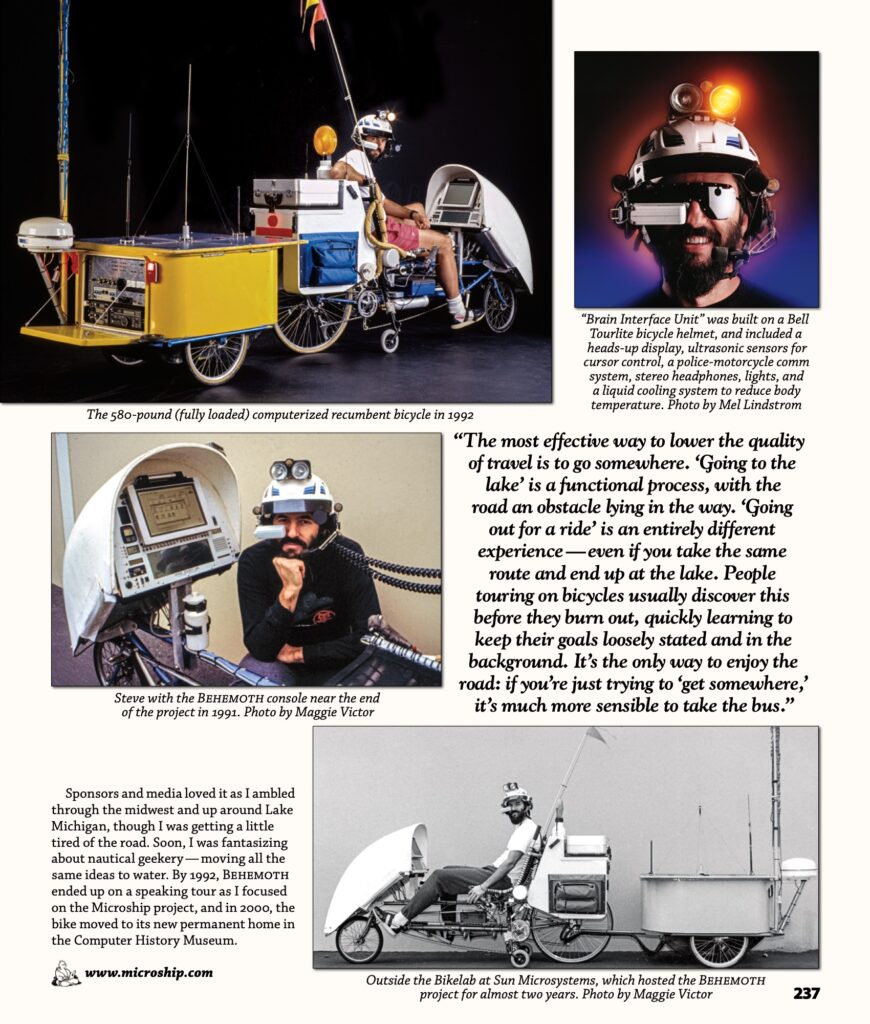

Here we’re covering his first recumbent bike, the Winnebiko, built in the ’80s. It’s the simplest of his bikes, and the easiest to understand, especially compared to his 1989–91 BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine — Only Too Heavy), a 580-pound, 105-speed monster, costing some $1.2 million(!), a 3-year project supported by Sun Microsystems and about 140 other corporate sponsors. (BEHEMOTH is now ensconced in the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.)

Steve has posted an awesome amount of details on all his creations, so you can delve as deep as you wish with any of them, but this earlier model is a lot easier for mere mortals to understand, and therefore presented here.

The Winnebiko

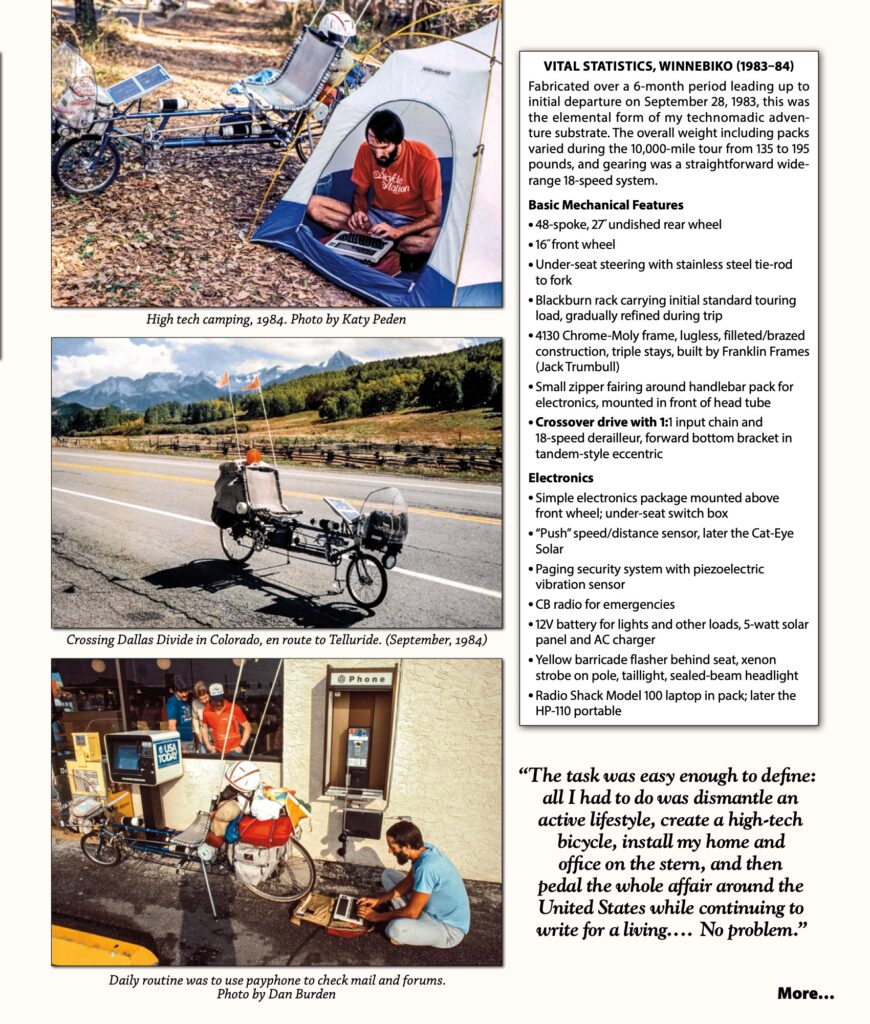

by Steven K. Roberts

This technomadic story begins at a time of primitive computer and communications technologies. Cellular phones did not yet exist, online services cost a few dollars an hour for cumbersome text-only services, and people were debating whether one could actually work at home instead of the office.

I had just turned 30, and was on a quest for geek adventure fueled by publishing — a way to escape Ohio suburbia and combine all my passions into a nomadic lifestyle. After six months of obsessive preparation, I hit the road in September, 1983 on a custom recumbent bicycle with a solar-powered portable computer (the venerable Radio Shack Model 100), a CompuServe account, and a base office.

The idea was to simply have a way to stay in touch with clients and publishers while traveling full time, and as the months passed, I refined the toolset to render my physical location less and less relevant.

“Work at home? Work anywhere!” I wrote exuberantly, sensing that I was pedaling at the cusp of major cultural change.

This started simply as a high-tech bicycle tour, but what I didn’t expect was that the media would be enchanted by the idea of nomadic connectivity — combining new information tools into a mobile lifestyle that also happened to be visually distinctive with the recumbent bicycle, solar panels, antennas, and more. My bike trip was becoming a career.

As the adventure unfolded, I wrote a book called Computing Across America, produced columns and features for various magazines, did interviews, and watched my whole life change. Ohio suburbia faded to a speck in my rear-view mirror, and I began fantasizing about the next generation of technomadic tools.

This first trip took place between 1983 and 1985, but the technological world was rapidly evolving and parts quickly came to feel obsolete. By late 1984, I had switched to a much more capable Hewlett Packard Portable, and was designing a system to let me type on a handlebar keyboard while riding, as well as maintain a steady wireless link to readers. When the 10,000-mile mark rolled around (appropriately enough, in Silicon Valley), I decided to take a year off from the road to finish the book and build a whole new system onto the trusty frame that had carried me this far.

Winnebiko II

10,000 miles on the first version gave me lots of time to fantasize about what I really wanted: a binary chord keyboard in the handlebars talking to a computer screen on the console. In the summer of 1986, I built the Winnebiko II system onto the same recumbent frame, with a computer that let me type in binary at about 35 words-per-minute while riding. There was also a packet-radio mailbox for email and chatting with fellow hams, and the bike was equipped with a speech synthesizer to let me remotely chat with people standing around the bike.

The version covered an additional 6,000 miles on both coasts of the U.S. The network culture was also growing rapidly, becoming quite a community — an online sense of home that by now had completely replaced the geographic one long ago left behind in Ohio.

But technology was also exploding, and by 1988 I was again having serious geek fantasies. The second trip paused in Florida when my Computing Across America book came out, and after few months on the speaking circuit (via a converted school bus) it was time to do it right.

BEHEMOTH

For nearly six years I had been wandering, collecting stories, doing interviews — frolicking in this new world where physical location was less relevant than one’s choice of network providers. This was a very addicting lifestyle, and I survived by putting out a journal called Nomadness, selling my book, and freelance writing.

But technology was moving much faster than the ambling pace of a guy on a bicycle. I had become a spokesman for the very gizmology that was leaving me behind, stuck in the slow lane, getting whiplash from rubbernecking the miracles zipping by without having nearly enough lab time to keep up. Something had to be done; what I needed was a new machine — one with a software-defined architecture, a set of resources that could be reconfigured on the fly, a glass cockpit, more power, more communications, more file storage — more everything.

This resulting three-year project took geek bicycling to an extreme, and looking back three decades later it’s amusing to realize how much of it could have been satisfied by a modern smartphone, ham radio, and solar power system.

Weighing in at 580 pounds (fully loaded for touring), BEHEMOTH was a 105-speed beast, packed with technology from bow to stern. There was a Macintosh in the console, and in addition to the handlebar keyboard, there was a head mouse to allow cursor control while underway. A DOS machine appeared in a heads-up display below my right eye, and other workspaces appeared on dedicated LCDs behind and below the Mac. There was even a SPARCstation behind the seat, as I always wanted to ride a Unixcycle . . .

An on-board network allowed anything to talk to anything, and, the machine was packed with communication technology, including a huge ham radio station and a satellite earth station for electronic mail via the Internet — in 1990. And there was technology to compensate for the weight of all the technology; there were pneumatically controlled landing gear that could be deployed to give me stability when climbing a steep hill in the ultra-granny gear.

Sponsors and media loved it as I ambled through the midwest and up around Lake Michigan, though I was getting a little tired of the road. Soon, I was fantasizing about nautical geekery — moving all the same ideas to water. By 1992, BEHEMOTH ended up on a speaking tour as I focused on the Microship project, and in 2000, the bike moved to its new permanent home in the Computer History Museum.

You must be logged in to post a comment.