High Tech Nomadic – MacDigest

This publication of the Los Angeles Macintosh User Group was a great venue for this general overview of the whole bike epoch (which also appeared in similar form in my various self-published pieces like the later From BEHEMOTH to Microship book). With a Mac Portable embedded in the bike’s console, controlled by ultrasonic head mouse and handlebar-keyboard, the bike quickly became iconic, so to speak. From their blurb at the beginning:

“Steve Roberts travels the world on a recumbent bicycle loaded with high tech computer gear. The 300-pound bicycle he calls BEHEMOTH includes some of the most advanced communication technology available today. A Macintosh Portable and custom HyperCard stack control a complex array of microprocessors, 82-watt solar panels, and radiation and vibration detectors.”

by Steven K. Roberts

MacDigest

July, 1991

I’m not sure what started my addiction — how I graduated from small doses of bush league adventure to the hard stuff. I do know that the type of movement doesn’t matter very much: a computerized recumbent bicycle is appropriate and endlessly entertaining, but it’s not the heart of my wanderings. The heart is a wild throbbing thing of thermos coffee, road maps, strange eyes, and exploratory kisses — of faded packs and mountains, harbor smells and camp stoves.

— Steven K Roberts

from “The Other Woman“

For seven years, I have dedicated all available resources to the pursuit of high-tech nomadness — a freewheeling lifestyle aboard a computerized recumbent bicycle. Now in an extended Silicon Valley layover after 16,000 miles on the road, the bike is undergoing radical change, becoming an autonomous mobile information and communication platform… powered by the sun… propelled by human muscle… linked via satellite with global information networks. In the process, thanks to hundreds of involved companies and individuals, the bike is becoming a showpiece of future technology, with radical human interfaces, dynamic multiprocessor system architectures, and experimental communications links hinting at what may lie ahead for society at large.

What does this all imply? How does it work? What’s the point? And why does nomadness continue to be such an alluring lifestyle? This document presents a brief history of the adventure, some commentary on living a nomadic high tech existence, and an outline of the new system.

Columbus, Ohio: Inspiration for Long-distance Travel

Way back in 1983, I was doing what most struggling young freelancers do: taking on a succession of projects, destroying old passions by turning them into businesses, and trying to make enough money to stay afloat. My lifestyle had become suburban, and as I clattered around my boring acre in an itchy haze of midwestern pollen and lawn mower smoke I wondered what had gone wrong. “Freelancing” was an illusion; I was chained to my desk and deep in debt like everyone else. Stuck.

Worse, change, evolution, and growth had begun to sound like vague counterculture concepts instead of the basic objectives of daily living.

Where had all my passions gone? One afternoon I listed them: writing, adventure, computer design, ham radio, bicycling, romance, learning, networking, publishing…each of these things had at one time or another kept me up all night in a delicious frenzy of fun and giddy intellectual growth. Yet my reality had become one of performing decreasingly interesting tasks for the sole purpose of paying bills, supporting a lifestyle I didn’t like in a house I didn’t like in a city I didn’t like. I had forgotten how to play. Could it still be possible to construct a lifestyle entirely of passions, or was losing the spark a sadly inevitable part of growing up?

Combining the passions in my list and abandoning all “rational thought,” the obvious solution was to simply equip a recumbent bicycle with ham radio and computer gear, establish a virtual home in the nascent online networks, and travel full-time while writing and consulting for a living.

Was such a mad idea really possible?

Computing Across America

Amazingly, it was. Six months later, to the obvious dismay of parents and girlfriend, I hit the road — having liquidated the 3-bedroom ranch in suburbia and most of its contents. The bike was a custom recumbent dubbed the Winnebiko, the computer a little Radio Shack Model 100 laptop, the data communication link CompuServe, the power source a small 5-watt solar panel.

Immediately it became obvious that I had hit upon something significant. In 1983, the concept of decoupling from a fixed home without becoming a bum in the process was alien to most people, especially with the trappings of high technology allowing an active freelance lifestyle. Daily email from pay phones became routine, and soon the magazine assignments started pouring in — then a book contract for Computing Across America. I was interviewed in almost every town I passed through, appeared numerous times on national television, and amassed a loyal following of fellow online denizens who offered support facilities all over the country.

For 10,000 miles I wandered solo, high on the energy of beginnings and change, never really seeking publicity but becoming amazingly well known. But it wasn’t me so much as the Winnebiko… a machine that eloquently symbolized the daring notion that people could indeed be free, follow their dreams, and break the chains that had always bound them to their desks. In small towns and big cities all across America, I saw the same faraway look, the same dawning of understanding. “Mah gawd, man, you mean to tell me you’re runnin’ a business from that thang? Reckon I could do somethin’ like that? Always did wanna see the world…”

Some of it was the ancient lure of the road, some the glitter of new technology. (“Are you with NASA?” asked a midwest farmer one day.) But through it all I was not only championing the linked causes of freedom, risk-taking, solar power, laptops, networks, and human-powered vehicles, but I was also learning at a furious pace… and becoming deeply frustrated with the limitations of my machine.

I couldn’t write while riding. I depended upon clunky wireline phone connections. I had only 5 watts of solar power. My radio links were tenuous at best. The technology offered much more…

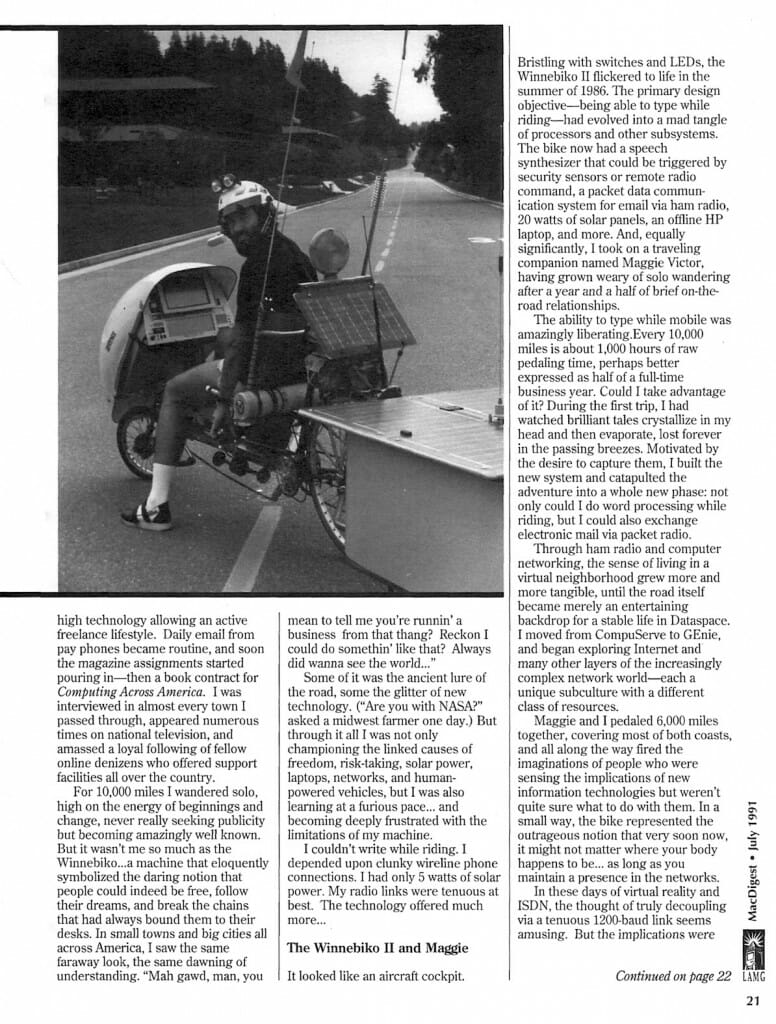

The Winnebiko II and Maggie

It looked like an aircraft cockpit. Bristling with switches and LEDs, the Winnebiko II flickered to life in the summer of 1986. The primary design objective — being able to type while riding — had evolved into a mad tangle of processors and other subsystems. The bike now had a speech synthesizer that could be triggered by security sensors or remote radio command, a packet data communication system for email via ham radio, 20 watts of solar panels, an offline HP laptop, and more. And, equally significantly, I took on a traveling companion named Maggie Victor, having grown weary of solo wandering after a year and a half of brief on-the-road relationships.

The ability to type while mobile was amazingly liberating. Every 10,000 miles is about 1,000 hours of raw pedaling time, perhaps better expressed as half of a full-time business year. Could I take advantage of it? During the first trip, I had watched brilliant tales crystallize in my head and then evaporate, lost forever in the passing breezes. Motivated by the desire to capture them, I built the new system and catapulted the adventure into a whole new phase: not only could I do word processing while riding, but I could also exchange electronic mail via packet radio.

Through ham radio and computer networking, the sense of living in a virtual neighborhood grew more and more tangible, until the road itself became merely an entertaining backdrop for a stable life in Dataspace. I moved from CompuServe to GEnie, and began exploring Internet and many other layers of the increasingly complex network world—each a unique subculture with a different class of resources.

Maggie and I pedaled 6,000 miles together, covering most of both coasts, and all along the way fired the imaginations of people who were sensing the implications of new information technologies but weren’t quite sure what to do with them. In a small way, the bike represented the outrageous notion that very soon now, it might not matter where your body happens to be… as long as you maintain a presence in the networks.

In these days of virtual reality and ISDN, the thought of truly decoupling via a tenuous 1200-baud link seems amusing. But the implications were staggering. Home, quite literally, became an abstract electronic concept. From a business standpoint, it no longer mattered where we were, and we traveled freely, making a living through magazine publishing and occasional consulting, seeking modular phone jacks at every stop.

But after three years with the new bike, I could no longer ignore the advances of technology. The Winnebiko II was architecturally inflexible, anemic, fragile, difficult to service, limited to a single poor LCD screen, underpowered, and, well, boring by today’s standards. It’s time to do it right!

The Grand Turing Machine… WHY?

So what is the objective here? Is this another step in the layering of progressively niftier technology onto my faithful old recumbent bicycle frame until I’m too old to huff it up a hill? Is there a central dream? Or am I just a gadget freak, propeller-head, and yuppie hobo all rolled into one, too set in my wandering ways to consider settling down?

These thoughts were much on my mind as I pondered the design of a new machine. The scope of this one is truly frightening: nearly $1 million worth of bicycle, including the value of professional time (at 350 pounds, that’s $178/ounce); 2-3 years to complete; about 150 corporate equipment sponsors along with a couple dozen occasional assistants, machinists, technicians, and consultants. What could possibly motivate me to concentrate so many precious resources into a ponderously heavy machine, just to expose not only it but my own body to the violent drunken terrors of the highway?

Hmm.

The initial need to escape suburbia for a life of adventure has long since been satisfied. So has the basic tire itch, the lust for a piece of asphalt, the curiosity about hot fleeting romances and the mysteries of small towns. I have already proven I can “do it,” whatever that means. So, what is it now? Inertia? Addiction to movement? A sense of not having finished the job yet? Vague dreams of another book, perhaps even with a real publisher this time? The continuing appeal of the spotlight? A lifelong love of whiz-bang technology? It’s a little of all that, but much more besides. Consider the suite of motivations:

- LIFESTYLE PROTOTYPE. Future society will be virtually paperless, energy-efficient, dependent upon wide-bandwidth networking, and generally cognizant of global perspective through routine communication across decreasingly relevant borders. It is not too early to prepare for this: we need the ideas, the tools, and an awareness of the prob- lems that accompany fundamental shifts in the meaning of information. The new bike, and the lifestyle that results, is a case study and feasibility test for much of this. I have already seen the effects of my earlier travels, especially back in 1983-4 when laptops, online services, solar panels, and all were all so strange that people were startled into understanding. During the next trip, I will be appearing regularly at schools to help plant the seeds early (while reminding students that the obvious choices are not the only ones).

- CONSULTING BUSINESS. Industry is requiring increasing specialization of

its workers, due to the overwhelming amount of expert knowledge associated with every technology. This yields positive results but at a severe cost — specialists inevitably lose sight of the big picture. There is thus a growing market for people who travel continuously among specialists, cross-fertilizing at every stop. No trade journal or annual conference can accomplish as much as a renegade cadre of curious technoid generalists, on the loose in industry. The companies that recognize their own narrow focus and take steps to keep it in context gain a competitive edge, and my nomadic lifestyle and extensive support technology keep me in touch with a very wide range of pursuits… and marketable. - PRODUCT POTENTIAL. The new system addresses a number of basic needs: autonomous power generation, global communication, soft-architecture real-time control, nomadic publishing, security… and more. These needs are by no means unique to me, and casual market research suggests that there could be a wealth of spinoffs with the right strategic partner. Sort of a mini-NASA…

- WRITING AND PUBLISHING. People are endlessly fascinated by life on the edge, the adventures of travelers, and peeks through curtains into other lives. Travel and writing are thus inextricably linked, and by carrying the most sophisticated tools available for biketop publishing, communication, and information-gathering, I minimize the number of excuses for not being productive while raising reader curiosity in the process. For an author, this whole gambit is a gold mine: endless story material, superb tools, and easy marketing based on a recognizable image.

- ADVENTURE. This goes without saying. High-tech nomadness is fun, and my travel style insures interesting contacts in strange places. Routine life is impossible on a computerized recumbent with solar panels and a thicket of antennas… and there’s a LOT of world to explore out there. Having had a taste of it, how could I spend my life in one place?

- SECURITY. I once wrote that “the greatest risk of all is taking no risk.” While that may be true, it does not mean that I relish the idea of being robbed, run over, or left to die of thirst with a broken axle in the desert. The new bike is designed with enough different kinds of communication gear to virtually insure that I can get a message out if necessary. Usually help is only a call away, via ham repeater or cellular phone — in more remote areas, a few moments’ preparation puts me on the HF bands or into a communication satellite.

- COMMUNITY. This may sound odd at first, given the classic “loneliness of the long-distance traveler.” But nomadness is the most social lifestyle imaginable for two reasons: global networking and the timeless energy of beginnings. The traditional concept of stability, normally restricted to neighbors, associates, and the familiar things that define “home,” is now distributed around the world and constantly refreshed by encounters on the road. Home is everywhere, and I am constantly amazed by the intelligence and imagination lurking in the most unlikely places. (The mainstream high-tech world is provincial and technocentric… seldom recognizing that wizardry can thrive in backwaters not steeped in the vapors of silicon. From unexpected quarters come new ideas.)

- TECHNICAL CHALLENGE. Finally, one of the most deeply alluring parts of this whole affair is the project itself. This transportation/communication system borders on madness, so diverse and intertwined has it become. The engineering aspects of this, ranging from sophisticated CAD tools to fancy new adhesives, represent a seductive and multifaceted learning curve coupled with the pure joy of creating something exciting. And one of the best parts is that the media visibility keeps attracting new sponsors, allowing me to select the very best technology that industry has to offer without being stopped in my tracks by something so mundane as cost. How could a dedicated hacker/tinkerer ever abandon such a project?

Well, there are now 49 days to departure, and I’m in the D phase of the PFD phenomenon that most concisely describes my work habits (Procrastination Followed by Despair). It is clear now that the machine will indeed roll. It has gears, brakes, lights, a Cateye, and a radio… all working. There’s pack space, and most areas are waterproofed. Many subsystems are nailed down on the bike and have been tested on umbilici, but now await cabling or software to become useful. The primary task is to complete as many “lab” tasks as possible in the next 7 weeks… for after that, I will no longer have the milling machine, hardware inventory, high-speed scope, huge work area, or all those wonderful new toys still shrink-wrapped on the bench.

Good thing this is a passion, eh?

— Steven K. Roberts, May 5th, 1991

For all the curious, Steve briefly outlines the components of Behemoth…

The bike is an 8-foot recumbent, meaning that I sit in a relaxed position with my hands on control levers at my sides and my feet latched into a pedal assembly out in front. Behind the bike is a 4-foot yellow trailer with solar lid, flip-down communications bay access door, and numerous antennas. In front of me is a large control console contained within a smooth white lexan fairing, presenting a panel with three large LCDs and numerous other instruments. Behind me a large white “RUMP” provides additional equipment space, a refrigeration system, more antennas, and a docking bay for an aluminum manpack with its own small solar panel. Atop my head is a decidedly bizarre helmet with heads-up display, motion sensors for cursor control, lights, a fluid heat exchanger for body cooling, and an audio system. The whole system weighs about 350 pounds… plus me… and thus has 54 speeds, deployable “training wheels” for mountain climbing, and 6 brakes to help me survive the descent.

For more information on Steve and his travels… check America Online’s Macintosh Communications Forum (Keyword: MCM). Steve hosts the High Tech Nomadics SIG there. At the time this was written in May, Steve also noted that the July issue of Discover Magazine; the August issue of Bicycling; the next Mondo 2000; and the 5/28/91 issue of the San Francisco Examiner would all contain articles on his “passion.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.