Bikelab Report #9 – BEHEMOTH Bike Tech

Photo: David Berkstresser at Cecil, the Rockwell milling machine in the Bikelab. (Cecil be ‘da Mill)

3:15 AM. It’s becoming a familiar time — a favorite one, even. This time of day, there are few commercials on the radio to disrupt the back-to-back jams. There are no phone calls, few stray beeps from the SPARC, none of that constant temptation to invoke Aladdin to check GEnie or browse America Online. The time is mine; the only hint of other life is the occasional passage of a sleepy guard making the rounds or the clatter of a night janitor emptying trash. (They must wonder… passing my locked door in the middle of the night, hearing cranked music of every genre, the growl/whirr/whine of Cecil/Makita/Dremel followed by the roar of the Great Sucking Monster whisking deadly aluminum chips from equipment bays… what’s that guy DO in there? He never leaves!)

Occasionally I do leave, of course. Silicon Valley by day is a frenetic zoo, a place of angry traffic, clutter, stress, and crowds. Sometimes I have no choice: I drag my entire body around the city just to acquire a $6.00 part, a process of dubious efficiency. But by night, it’s a different world out there… quiet and laid-back. I do my food shopping, gassing-up, and wallet-refilling after midnight, skulking through the darkness with the graveyard shift, breezing through intersections that would have me grumbling by day, strolling across El Camino while hearing only silence.

Tonight there are no errands. I’ve been extending the power bus from the trailer, through the hitch, into a small RUMP sub-panel, and up to a distribution area in the main RUMP bay. It’s now only one more hop to the console, and then things will start to flicker to life. Perhaps that’s why I’m working late — this is an exciting epoch in the creation of a system (much more so than the endless acquisition and repackaging of isolated components, marathon list-editing, and timeless staring into space as vaporous n-dimensional images of BEHEMOTH evolve in the wetware CAD system — virtual revision levels incrementing furiously as a massive hierarchical file structure becomes at once reassuringly structured and hopelessly intimidating).

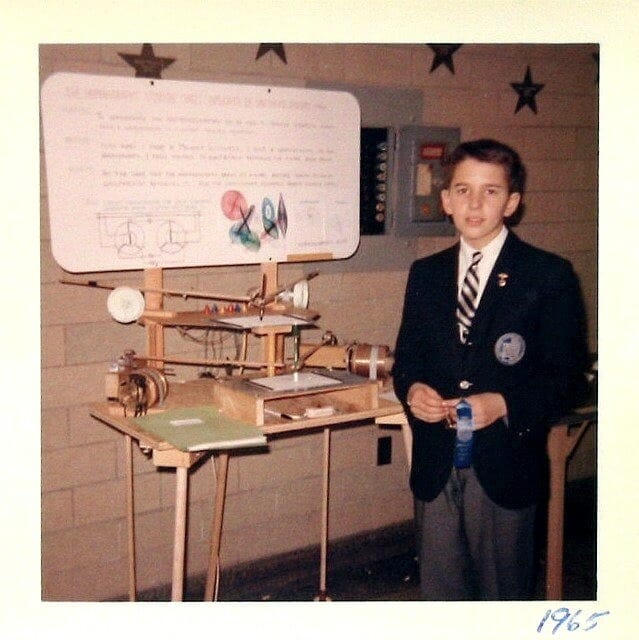

The only thing that makes this entire project tolerable is the fact that it’s a PROJECT, not a job. That ethic began in grade school, when I noticed the vast behavioral gulf between science fair projects and homework. The latter was irrelevant noise, busy work involving neither invention nor creativity. Why bother? The same tasks had already been done thousands of times by others, and would doubtless be repeated more or less identically by thousands more. They obviously didn’t need ME to go through it all again. But science fairs! Every year, the pressure would build relentlessly as I slaved in my basement lab building acoustic speech synthesizers, speech compressors, servo-linked harmonographs, AC induction magnets, relay logic machines, diode-matrix-based Morse code translators… whatever outpourings of 60’s technopassion happened to enchant me at the time. Each was unique, an obsession, lovingly crafted on a tight deadline and then documented at the last possible minute (just like in industry) — and those 7 annual marathons had more to do with passion and curiosity than fear of tests.

Those were formative years, so it’s no surprise that I’ve spent the last 20 doing everything possible to avoid employment. It has begun to occur to me that this whole bike system — all 8 years of it from chrome-moly frame to Ethernet, from tire pump to satcomm, from sponsor deals to teeth-clenching mountain grades — is just a colossal science fair project, thoroughly laced with romance, adventure, and the sweet mad essence of life itself…

Chaos and the Pedaling Emulator

In this issue’s emailbag, we have this food for thought from Mike:

I know that in most Sun farms, the order in which things reboot after, say, a power failure can be critical. If this guy’s yellow pages aren’t up yet, the main file server will get stuck listening to that guy over there, who can’t boot without the right yellow pages, and so forth and so on. This has to do with, I suspect, an as-yet-unexplored offshoot of the science of dynamical systems, aka chaos theory (a subject I’m studying in some detail ’cause I’m geyser-mad and I want to model geyser eruptions with chaos theory). The point is that when you have lots of computers busily interdepending, you can have “pseudo-chaotic” operational configurations, which are stable, but broken.

Sooooo… just wondering, mind you… are you sure that the happily operational configuration of SPARC, PC, Mac, and Forth engines is the ONLY possible configuration, and one which will be reached every time things come up? Just a thought.

— Mike O’Brien

Yikes. A useful warning… thanks!

— Steve

And I thought you might enjoy this twist in BEHEMOTH’s design contributed by Digital Equipment Corp:

As part of a non-competitive joint venture with Sun Microsystems and other software and hardware vendors, Digital Equipment will contribute a key ingredient to Steven Roberts’ BikeLab. Still under development, BEHEMOTH has been described as a cornucopia of high tech gadgetry on wheels. The bike is being prepared by Roberts for the summer riding season in a lab donated by Sun Microsystems. Since he will certainly be kept busy on his trip attending to hardware and software issues, Digital’s contribution will allow him to offload the effort of propelling his bike onto a pedaling emulator.

The device involves a mechanical device that emulates the human pedaling motion. The pedal will be driven by a metal arm-like device that in turn is powered by a cylinder sliding up and down in a tube. During the power stroke the cylinder will be forced down by the explosion of some sort of combustible material that must be refilled with each rotation. Digital engineers are confident that Roberts will be able to find plentiful supplies of fuel on his trip.

Bike tech

Oh yes. That reminds me. There… IS a bicycle somewhere underneath all that stuff, isn’t there? Often I forget that and end up with nasty surprises, like trashed bearings and stretched chains, startled and betrayed by real-world mechanical wear when I’m thinking digitally. For most of those 16,000 miles I pedaled around with the same parts I acquired back in 1983, some of which were old even then. Hard-core bikies would occasionally sneer at my antique Campy high-flange front hub, and I grew quite tired of replacing headsets every few hundred miles.

Well, things are changing. With 350 pounds (I, um, HOPE that’s all there is) of cargo, some of the component decisions are critical. With the help of bike wiz Greg Davis, machinists Dave Berkstresser and Ron Covell, and the bicycle industry itself, I’ve been re-doing BEHEMOTH from the frame up. Let’s take a mechanical tour, starting at the front…

The front wheel is a 16 x 1-3/8 alloy rim with 36 holes, custom made by Weinmann for the Avatar recumbents about 10 years ago. The new hub, currently under construction, is a custom variable-reluctance motor-generator assembly spinning on SKF sealed bearings… more on that when it becomes a reality. A Mathauser single-cylinder hydraulic rim brake is mounted on the Ishawata fork crown, and brazed to this crown is a 1/4-20 stud that holds a teflon-lined rod end for the steering linkage. The headset is a sealed Chris King unit — the latest and hopefully the final iteration in my endless quest for one that can take the abuse of heavy equipment. This headset has a good reputation among the hard-core mountain bikers (and I’ve also shock-mounted the new console to filter out high-frequency impulse energy).

Moving back, we come to the crankset. From 1983 until last week, this has been a 185-mm TA tandem crank, with a single drive chainring on the left side. Now it’s a custom chrome-moly 191-mm crankset made by CQP, with sealed bearings installed in the original eccentric that once allowed me to adjust for chain-length variations on the tandem-style 1:1 crossover drive. Attached to the cranks is a pair of Cycle Binding pedals, whose floating heads lock into a very well designed shoe system. Unfortunately, the company went out of business before I could hit the road… but the product seems to be excellent and I guess I’ll find a new vendor when these eventually wear out.

The transmission is perhaps the most striking mechanical feature of BEHEMOTH (at least until the landing gear assembly is built — details in a future issue). It has 105 speeds, ranging from a killer granny gear of 7.87 inches to a robust tall gear of 122. This is accomplished via three derailleurs: a rear unit hacked on the the port-side crossover drive assembly in addition to a more-or-less conventional 21-speed indexed system on the starboard side. The gears are:

- D: Drive ring on crankset: 24

- X: 5-speed cluster on crossover: 18-26-34-40-46

- F: Standard front triple: 19-36-44

- R: 7-speed freewheel cluster: 13-15-17-20-24-28-34

You can think of the gear chart as a 3-D matrix of 5x3x7 cells, calculating any ratio as (D/X)(F/R)27. Incidentally, a couple of those gears involved a bit of trickery: the 5-speed crossover cluster is built on a modified Shimano crankset (arms removed and lathe-turned to point symmetry). The top three rings are on the 110 mm bolt circle with some special spacers, and the other two — aided by a “Quad Tamer” — are on the 74 mm circle. Likewise, the triple had a bit of help — that 19-tooth ultra-granny is mounted on a Limbo Spider that allows the use of a standard steel cog in place of the usual inner chainring. The spindle that connects them obviously is longer than usual — it’s another custom job from Gary Cook at CQP, 142 mm long.

Incidentally, I am often asked why so many gears. A 105-speed bike? Isn’t this a bit excessive, in addition to being harder to say than “18-speed”? Not at all — this not only provides a stunning granny gear of less than 8 inches (1.4 mph at a cadence of 60 RPM — now you know why the landing gear), but also gives me enough easily addressable ratios to allow a good impedance match between body and bike under any load conditions. That’s important when the whole mess, body included, is well over a quarter ton…

Derailleur choices are based on construction quality, integration with the selected shifters, and availability. I do not yet have any road time with this component suite, so it is not meant to be a recommendation. At the moment, we have a Shimano Deore half-step front derailleur, a SunTour XC Pro on the rear, and an older SunTour wide-range unit on the crossover transfer assembly. I’m experimenting with the new Grip Shift from SRAM for the main two, and a pair of classic SunTour Barcons mounted in the forward seat tubes for the crossover and the drag brake. Chains are Sedisport ATB on the left and SunTour XC Pro on the right.

The rear hub is a double-threaded Phil Wood tandem unit, with 48 holes. 14-gauge DT stainless spokes connect it to the Weinmann concave alloy rim in cross-4 symmetrical UNDISHED pattern. I can recommend this highly… my undished 48-spoke wheels have taken 16,000 miles of heavy abuse without ever breaking a spoke. The only damage I’ve ever had with this configuration occurred in Whiteville, NC, when a pickup-truck door materialized in my path and somehow drove the derailleur into the spokes, forming a highly-effective one-shot braking device that contributed significantly to the suite of bike and body ills that suddenly manifested themseves. (While recovering from back and leg injuries and waiting for parts shipments in Whiteville, by the way, I wrote a gripping story called Blood in the Spokes. It observed, at one point, that “I am out spokin’ at times… rolling from a wheel-truing deal to true wheeling-dealing, toiling at truth while reeling from the raw deal of a rear wheel’s real ruin…”)

The trailer wheels are 36-hole Suzue sealed hubs with butted stainless spokes to 20″ Sun Chinook rims (whatever those are) and Haro slick tires. The bike’s rear tire has historically been a Specialized 1-3/8 Expedition, which they discontinued and then apparently re-introduced (if the lastest Nashbar is any guide). I’m considering others, including the lively Michelin Hi-Lites and something Greg is recommending. The front tire is whatever I can get — not much quality rubber exists for 16″ wheels. Kids’ sidewalk bike tires from Western Auto typically last 1,500 miles, but it would be nice to optimize rolling resistance et al with something made for the “serious” bike market.

In the braking department, I have a pair of Mathauser hydraulics — single-cylinder on the front, double on the rear. There has always been either an Araya drum or Phil Wood disk on the rear… I’m dissatisfied with both for various reasons and am looking into a custom motorcycle-style hydraulic to use as a drag brake and wet-weather insurance. There’s also the regenerative system under computer control, of course — the first line of stopping defense — and I’m hoping to add a pair of brakes to the trailer as well. The problem is that I have only so much grip strength, and ganging brakes on the levers actually has a negative effect on stopping power due to additive power-transfer losses. This calls for some other energy storage device, which translates into either a surge system (tricky design but interesting) or a linkage that captures the force imparted to another brake in order to actuate the next two down the line. Later.

Finally, the frames. The bike frame is a work of art, a supremely reliable and elegant custom job by Jack Trumbull of Franklin Frames in Columbus, OH. The steering geometry is perfect, which is to say almost “dead,” with no tendency to oversteer like so many commercial recumbents. It has about 1/2″ of positive trail. Naturally, it’s 4130 Cr-Mo. A thick tandem-style heavy-wall bottom tube and triple stays contribute to overall stiffness and resistance to overload fracture.

The trailer frame geometry is defined by the original Equinox trailer that formed a template for this unit. I tossed the original upper structure of aluminum and fabric and built the cardboard-fiberglass body… then noticed that the original frame was now too fragile for the application.

Paul Sadoff of Rock Lobster Cycles built a beautiful new one of heavy 4130, and now, if I had the strength, I could probably haul Cecil the 900-pound milling machine without frame failure. But I won’t. This obsession with having it all has gone quite far enough!

Jeez. No wonder this is all a shock. Looking back over the foregoing, I realize how little attention I’ve paid to bike-tech until recently — it’s easy to treat the bike itself as a chassis and focus all attention on the whiz-bang gizmology layered atop it. Problem is, failures of bike components can leave me stranded or worse, so this time money is no object and I’m depending on help from bike-savvy experts in the business. It’s starting to show…

General Progress Report

In other news, the cable harness is now to the point where the battery management and raw power distribution span bike and trailer. The only hard part here was dealing with the fact that the two units can be disconnected. With the batteries nominally treated as one big unit, unplugging is no problem… but what happens if I leave the trailer charging in a sunny campsite and go for a ride with the SPARCstation running Frame via Ethernet to MacX? I come back with a low bike battery, plug in, and ZAP! A hundred amps flows for a few milliseconds, popping breakers and burning connector pins. The solution, suggested by Glenn Glassner, is elegantly simple: a monster iron-core toroid in the inter-battery bus slows down this initial surge enough to contain it within the parameters of my protection hardware. Disconnect, which would normally draw an arc from the collapsing field, is no problem — the batteries will always be at the same level by the time I unplug.

Much of the lab work lately has involved the Ethernet and the things that connect to it. I’ve been collecting the interfaces and software necessary to make Mac, DOS, and SPARC enviroments happy with each other — apparently a non-trivial task. I’ll report more when things come to life and I know enough to describe the unix-related components to this predominantly internet-resident audience without getting flamed for not knowing what I’m talking about. Fortunately, I’m here at Sun, so there is no shortage of unix, sendmail, NFS, X, TCP/IP, POP, and SBUS wizardry in the neighborhood. Latest: the IPC has been brought up by Ron Lee and Kevin Long, and should be installed as BEHEMOTH on the network this week to give bike developers easy access to the tools distributed around the net. And John Noerenberg at Qualcomm is working on modifications to Eudora, a public-domain mail program for the Mac, to handle the human interface end of the OmniTRACS satellite email link.

Those new packs mentioned in the last issue have been installed on the RUMP, softening the otherwise industrial appearance of the machine. (Oh yeah… PACKS! It’s a touring bike!) The new seat fabric is on, supported by 1/8″ stainless welding rod donated by Madco and about 80 Panduit black cable ties. And Dave Berkstresser’s freehand midnight milling madness has yielded a sort of art deco seat-and-steering assembly. This was done at the last minute to make the bike ridable for last week’s photo session with Discover Magazine:

Another Midnight Attack

The first midnight attack was the subject of a story in Nomadness last year, relating a wild inter-cultural adventure on a cold windswept beach in Humboldt County. The latest occurred last week.

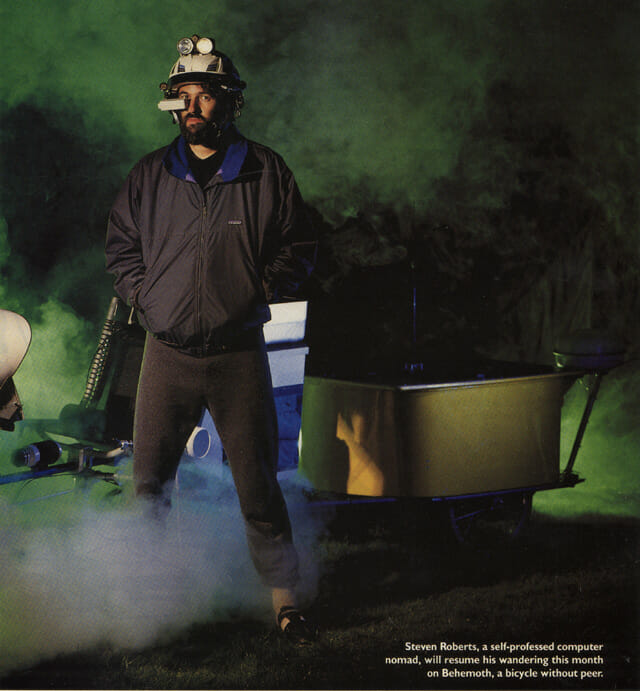

Discover Magazine is doing a story on all this, scheduled for the July issue — coincident with my departure. Chris the photographer (and his assistant) drove up from Santa Barbara to do the all-day shoot for the 4-page color spread, and Maggie pedaled down from the Santa Cruz mountains to lend a hand.

It went well all day — studio shots against a giant white backdrop hung from the roof of Sun’s building 4 (sort of the back-forty of the Mountain View campus, largely unoccupied and open at the moment). After a few hours of grinning on demand and generally looking high-tech, I took the bike outside for the obligatory afternoon-light shots on the waterfront. That went well also, except for the mechanical failure of revision 1 of the BYP mounting system <sigh>.

At 9PM we started the big setup. In the dark lawn next to the building, we hung a giant parachute from a pair of volleyball poles. The smoke machine was warmed up, and the photographer and his assistant spent a couple of hours experimenting with radio-synched strobes (green for the smoke, blue for the bike, warm for my face). We plugged the bike’s HeNe laser into the trailer’s 2500-volt power supply and taped it to a tripod, aimed at my head. Quiet on the set…

With the assistant generating clouds of smoke and the laser reflecting from a tiny mirror attached to my helmet (shades of the Borg), Chris went to work. Security guards stopped to watch the strange spectacle: blazing multicolored strobes illuminating thick smoke, a red laser beam knifing through the haze from my already bizarre helmet, tripods everywhere, a dew-sodden parachute billowing behind us. We looked like a Yes concert.

Suddenly… we were attacked by the Sprinkler System from Hell! With a mighty, wet WHOOSH, the ground all around us erupted in showers of water, sending people scurrying in all directions, cursing, shouting, trying to rescue thousands of dollars in photo equipment while not tripping over cables and shrubbery. I had my own problems: with a yell I took off across the lawn, still blinded by lights, pushing the bike over accursed fountains in search of someplace dry. I slowly became aware of a security guard jogging along behind me with a tripod under his arm, and remembered the laser. Oops.

It turned out that I had towed the tripod via the Uniphase laser head, ripping the high-voltage cable from the unserviceable assembly, and the guard was trying to help. Fortunately, no sparks flew… and the photo session was mercifully ended. So was the life of my laser.

And you thought this fame ‘n glory biz was easy…..

12.5 weeks and counting. Maggie, my erstwhile traveling companion, pedals north May 1 with Ryan recumbent bicycle, trailer, Daylab portable darkroom, laptop, solar panel, 2-meter Icom HT, and Venus Biscuit Snow (the cat). She’ll stop at the Kinetic Sculpture Race in Eureka over Memorial Day, then will be in Alaska by the time I truck BEHEMOTH off to Omaha to start RAGBRAI. Already we’re talking of a winter rendezvous in New Mexico. When the relationships of nomads evolve, the implications can be bizarre…

Back to the massive TO-DO list. Cheers from the Bikelab!

You must be logged in to post a comment.