Call to Nomadness

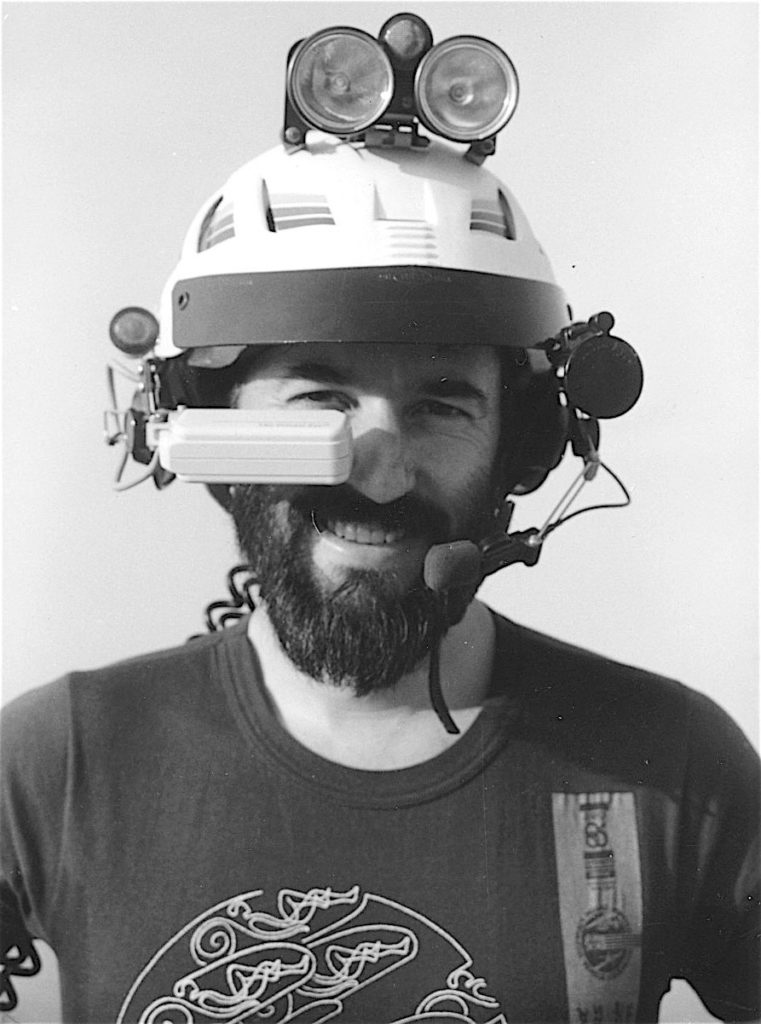

Here’s a fun bit of personal technomadic history from 1990… an earnest attempt to broaden the nature of my adventure by building a community of fellow wanderers with a wide range of skills. The possibilities were enchanting, and this document generated loads of interesting correspondence while BEHEMOTH (the third bike version) was in development. Although it never reached critical mass, it spawned some lifelong friendships and helped refine some of the system designs for modularity and scalability.

In 1990, more and more people were realizing that mobile connectivity through portable computers and newfangled networks really could enable a new kind of lifestyle, breaking the chains that once bound us to corporate desks and rendering physical location irrelevant (whether full-time or just as a way to reduce commuting). The tools were becoming practical enough that folks could become digital nomads without spending years building complicated geeky machines like the ones I had been dragging around since 1983...

This document is one of my favorite bits of history from those years, published in the Nomadness journal and distributed electronically via my Technomads listserve and Usenet.

An Invitation to Technomadic Adventure

by Steven K. Roberts

Santa Cruz, California

January 12, 1990

So. There you sit, reading something about Nomadness, perhaps having a few road fantasies and thinking about your life. It’s all mapped out in perspective: expectations, obligations, debts, and the massive amount of work necessary to support your chosen lifestyle (even if it’s a lifestyle you chose before you knew better, and no longer really want). Do you feel a twinge of wistful longing at the thought of taking off for a life of freedom and adventure? At the old dream of “chucking it all and hitting the road”?

It is possible!

Maggie and I are assembling a nomadic community, a mobile group of like-spirited folks who share similar passions. The whole idea is a bit mad, perhaps, but it sparks powerful reactions from the kinds of people we want as neighbors.

Step outside reality for a while and imagine…

Life in the Traveling Circuits

There will be somewhere between 4 and 10 of us, wandering the planet aboard networked recumbents. Most bikes will be relatively simple — perhaps just a laptop in the panniers, a small solar panel to take care of lights and accessories, a 2-meter ham radio, and a black box with an antenna that provides a data link to everyone else.

We’ll travel freely, not tied into a tight pack. If you have friends in Grass Valley, for example, you’ll want to stay with them as the rest of us camp; there may even be times when small groups separate from the rest and take a different route for a while. We’re all independent, each chasing whatever passions motivate us while sharing resources to make life easier and more fun.

Much of this resource-sharing has to do with information. The Winnebiko is ideally suited to being the host system and file server, since it already has 80 meg of hard disk, cellular phone modem, satellite earth station, and so on. So a daily routine will be for everyone to plug into my bike (via a cable or, more likely, the little RF black boxes) and up/download the day’s mail. My bike, linked twice-daily to the base office, thus becomes the hub of an arbitrarily-large network of nomads.

In this fashion, the major problems of communication, money management, mail forwarding, and maintaining the illusion of stability do not have to be solved independently by everyone who travels with us. We all share and help support the base office, staffed by one person and equipped with Mac, laser printer, PC, copier, voicemail, filing systems, fax, accounting software, and all the rest (much of which we already have).

But what keeps us fed? Implicit in this whole plan is the assumption that all nomads in the group are financially responsible for themselves. The easy way, of course, is to be independently wealthy — but since I can’t imagine what that’s like, I assume that everyone will be freelancing or remotely operating a stable business. I have supported my nomadness for over 6 years with a mix of writing and consulting, and this is the most obvious opportunity for others. But there are dozens of other angles…

Mobile Freelancing as an Art Form

Perhaps the most colorful example of creative ways to make a living on the road is provided by Michelle and Norbert “Nop” Velthuisen, cycling friends of ours in Holland. A few years ago, they set out for a round-the-world trip on homemade recumbents. Initial funding came from selling the house and compacting their lifestyle… but much of the road money came from doing aerial photography.

Aerial photography from bicycles? Sound crazy? Don’t forget that, as Clarke once wrote, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Nop would simply make contact in a strange town with a few land owners, show them his beautiful portfolio of 8X10 color glossy aerial photos from around the world, strike a deal, then go to work.

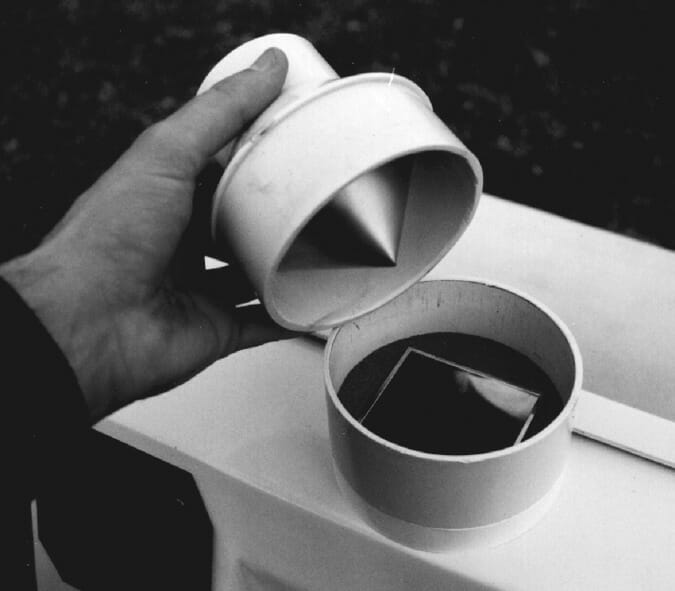

He would ride to the site, check it out, and uncork a PVC tube from the back of his bike. He would then remove a large kite… fly a remote-controlled camera over the client’s land… and start snapping pictures!

This was inevitably accompanied by great delight and amusement on the part of the locals, thus serving as both door-opener and cash-flow generator during their two-year open-ended journey. Now, isn’t it time for a high-tech cyclist to start selling aerial video from a radio-controlled, amateur television-equipped model airplane or helicopter? (Hey, if you build one, we can use it as a forward reconnaissance unit to check out the road ahead…) [2018 note: ah, the magic of drones… turn-key, cheap, beautiful, and so much easier!]

Other Possibilities

There are a lot of ways to make a living from passions, hobbies, freelance skills, and other creative shticks. Music performance or teaching. Lectures. Photography. Art. Writing. Consulting in any form. Online research and information brokering. Repair work. Video projects. Programming. Neural network research. Producing a coffee table book on rural mailboxes. Setting up dealers for a product. Fixing bikes in small towns and RV parks. Bringing new tech to the people. The possibilities cover a vast range of human pursuits, limited only by the basic constraints of equipment requirements and marketing. (If you are a machinist, for example, you’ll have a hard time finding work on the road unless you can find a machine shop to go with it, which is usually difficult.)

The common thread is information. If your product is information in any form, the idea is obvious — the stuff has no mass, is very portable, and can be conveyed via many media. If your product is the execution of a special skill based on information, then it is simply a matter of marketing yourself well enough to establish and then perform gigs while passing through. Within obvious constraints (including regulatory ones that affect certain professions), this leaves almost endless possibilities.

One “job opening” that may appeal to someone is to run a sort of specialized travel service to keep a few “guest bikes” occupied. This is a partly-baked idea at the moment, but I’ve seen a number of thriving adventure-getaway vacation businesses that make quite a lot of money by getting people into odd situations (and presumably back out again). In our case, we could equip a couple of bikes, then sell samples of our nomadic lifestyle by the week to people who love the idea but aren’t quite ready to give up the security of job and home. Even simpler, we could require customers to BYOB (bring your own bicycle). I have no idea how well any of this would work, and it could turn out to be a logistical nightmare, but if someone wants to run it and handle all the details it could provide full-time support for that person — plus a food-and-accommodation “kitty” for the entire group. With our massive ongoing media coverage, marketing should be easy.

Assuming that you want to travel and can figure out a way to make a living while doing so, then what next? Let me answer that by addressing some of the more common questions…

Technomadic Community FAQ

Where are we going?

Hard to say. Every time I try to predict that, I’m wrong. One of the beauties of this whole adventure is that it’s open-ended and thus does not get tied down to point-to-point commitments. (As I observed in Computing Across America, “If you think too much about where you’re going, you lose respect for where you are.”)

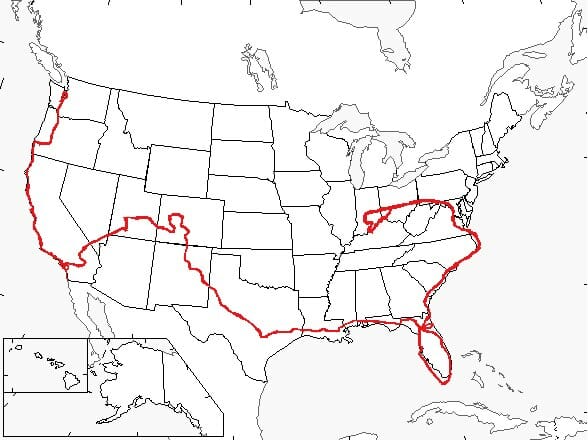

My best guess at the moment is that we will leave from either Seattle or somewhere in the Bay Area of California, heading in whatever direction the weather suggests. I personally want to spend time in the Canadian Rockies, Colorado and Utah, the American North-and Southwest, Canada’s Maritime Provinces, Europe, Russia, Australia, and Japan. But I’m open to anything, and this is a group endeavor.

Why recumbent bicycles?

Compared to regular bikes, recumbents are vastly more comfortable, more efficient, safer, infinitely more fun, and easier to pack with non-standard equipment. Besides, if you ride an old-fashioned bike along with a bunch of people on recumbents, you’ll fade into the background as far as media and public are concerned.

I strongly recommend recumbents for all these reasons, and if we’re all riding them our “look” will be more dramatic and consistent. Like it or not, image is an important factor… much of the flavor of the travel experience is determined by what people think of you. As my six years of travel have demonstrated, the technology choices not only make sense for the obvious central reasons but also have opened the door to public welcome, constant media exposure, and sponsorship. I’d like to keep the group’s image high-tech and efficient, and besides — we’re all marketing ourselves in some form.

And if for some reason you really don’t want to ride a recumbent, then I suppose that’s OK too. Mountain bikes, Moultons, solar hybrid vehicles, and ultralight aircraft are also possibilities… and I’m willing to at least consider a suitably teched-out mobile office (NOT a sag wagon) that can carry the laser printer, lab, and darkroom — and also precede us into towns to set up speaking, consulting, business, book-signing, teaching, or interview events.

Is ham radio necessary?

Absolutely! If you want to do this, then start working toward at least a Technician-class license now.

If you have ever cycled with a companion, you know the frustration of being far apart on the road and needing to communicate. “What’s he doing moping along back there?” “Damn, I wish that SOB would slow down, my knees are killing me!” “Did she see where I turned?” I’ve seen a lot of touring couples, tight-lipped and pissed, ruin their relationships through the inability to communicate (perhaps the precise opposite of riding a tandem, which can ruin relationships for other reasons).

Ham radio on the bike solves the problem perfectly (and with much more elegance than CB, which is inefficient, noisy, and — in most parts of the country — a cultural disaster). The little license-free 49 MHz headsets are nice for close (1/4-mile) range, but useless in most real-life situations. Ham radio, on the other hand, is both technologically elegant and your ticket to a global community.

Indeed, that’s the other major reason. When you pull into a strange town, key up a local repeater, and identify yourself as a bicycle-mobile ham operator, you have friends. You have a feeling of security, knowing you have instant access to police or other help if needed. You have local supporters who will leap at the chance to give you directions, find a repair part, or offer advice. You have dinner invitations and places to stay. And you have company, especially if you’ve maintained a stable presence in the ham radio magazines (and we have).

There are very few actual requirements in this project, but getting a ham license is one of them. Excellent courses are available by mail or through local clubs.

How will the group be selected?

On a totally ad-hoc, intuitive basis. I don’t want to fall into the role of “personnel manager” — I’m merely trying to pull together a stimulating nomadic community. Selection, therefore, is more on the basis of group consensus, personality, style, and energy than any specific “hard” criteria.

By the way, if you have some specific “survival” skills but are short on freelancing opportunities, this may still work for you. If the group gets big enough, we might find a way to collectively support a couple of people who can provide valuable resources — like medical skills, physical security, bike maintenance, translation, publication production, business management, wilderness survival, and so on.

What about dropouts and new arrivals?

Assuming we structure this intelligently (which probably means a minimum of structure), it should be no problem. Of course, once relationships are established, dropouts will cause the same kind of pain you see when people leave companies, but that’s a chance we have to take.

As to new arrivals, the big issues are system preparation time and the learning curve — we’ll help them along via the networks and then rendezvous on the road. I suspect, knowing the dynamics of travel, that there will also be short-term visitors who want to join us for a few hundred miles without actually trashing their lifestyles and becoming full-time wanderers. (Even nomads can have house guests…)

How will we deal with riders of different capabilities?

This can be an irritation, especially when you consider that some cyclists like rapid-fire hundred-mile days and others like to take short, relaxing rides between a succession of long visits. Our style is more slow than fast — I tend to prefer 30-50 mile riding days with lots of 2-3 day layovers, with an occasional marathon ride when circumstances offer no choice.

The nice thing about being radio-linked, of course, is that we don’t all have to stay in sight of each other (that would quickly drive us crazy). The faster and more ambitious riders could race ahead and set up camp, or even take multi-day side trips while the others plod along a straighter route. We’ll find a balance.

What about security?

This is always an issue, and is responsible for a fair percentage of the technology on the Winnebiko System 3. The black boxes I mentioned earlier are networked with my bike via UHF packet radio links, and can carry any kind of message including alerts from security sensors. Of course, this merely tells us if anyone is touching a bike — it doesn’t actually do anything about it. My bike includes a high-power ultrasonic pain-generator, microwave motion sensor, coordinate beaconing if it’s moved without a password, and a few other goodies, but all that takes a complex and heavy technological infrastructure that I don’t generally recommend.

The best lock is the human eye. On the road, you quickly get into the habit of being constantly aware of your bike and equipment, and everyone is basically responsible for their own stuff. One big advantage of multiple people, or course, is that there are more eyes, and often someone who’s willing to babysit the equipment while the others are off hiking, scuba diving, clambering, shopping, or whatever.

What happens when 8 people arrive in a strange town and need showers, food, and a place to sleep?

Interesting question. This is one of the reasons I insist on everyone being independent and responsible — a year ago when I first thought of this idea, I had the insane idea of structuring it like a company. This instantly cast me into the uncomfortable role of president, giving me unwanted responsibility.

There are a variety of techniques for finding accommodations, and sooner or later all nomads learn how to do it. In the meantime, the typical scenario is probably this:

We approach a town, and I scan my database of over 6,000 contacts — perhaps finding someone I know or a name from one of the traveler-support subcultures (including Mensa’s SIGHT program, Bicycle USA hospitality homes, AYH hostels, the Mosely list, Servas, and so on). Everyone else will check their own lists, which include old friends and whatever profession- or hobby-specific network applies (there are subcultures for everything). We get in touch and let our contacts know how many people are involved, sensing from the conversation whether we should seek an invitation or maybe invite them to visit our group camp.

If the only contact is an old friend in a small house, there will only be room for one or two people. In that case, we might ask if they have friends or other recommendations, and we all split up for the night (meeting at an arranged time on 2 meter ham radio). In many cases, some will camp, some will find a motel, and others will go home with hosts. It will be different every day, and we will often prefer to camp as a large group just for the fun of it — this is how our sense of community will deepen over time, while admitting enough variety to keep us from getting thoroughly sick of each other.

Based on enthusiastic response from a number of educators, we are also planning regular appearances at schools and colleges wherever we go — doing group presentations about our business, the technology that makes high-tech nomadness possible, the adventure itself, our nomadic community, and what we are learning of the world. In exchange, we will receive money, places to stay, contacts, and the deep satisfaction of bringing lively ideas to young people as an antidote to the isolation of textbooks and academia.

What about the inevitable personality conflicts?

It happens. I guess we’ll deal with it.

What if someone gets hurt?

Again, it happens. I’ve been injured twice in 16,000 miles on the road, both times badly enough to require an emergency room visit but not enough to require hospitalization. Statistically, it’s almost inevitable that someone will get hurt, perhaps even seriously.

First aid is no problem; we’re well equipped. But we will all need medical insurance, and it’s probably not a good idea to go into exhaustive detail with the carrier about the lifestyle you are contemplating! This is one of those areas in which maintaining the illusion of stability via a base office is essential (and it suggests the possibility of a group plan).

I also recommend having a savings account somewhere with a few thousand dollars to cover lost productivity, as well as repair, replacement, or shipment of your equipment if a serious accident occurs.

What will this cost me?

It’s hard to answer this with any precision, partly because there are a lot of ways to do it and partly because I’ve had most of my equipment generously provided by sponsors. And besides, you’re probably not trying to build a full-scale Winnebiko clone.

If you go out and buy the essential tools for this, including the bike, ham radio, solar power system, packs, minimal laptop computer, and camping gear, the price will approach $10,000 — plus whatever specialized equipment is required to support your business and techno-passions. Cost of living on the road is generally about $500/month, often less (no house or car payments!).

I financed my initial departure from Ohio suburbia with an all-summer garage sale, with only the solar panels, batteries, and online services sponsored. I think the Winnebiko System 1 cost me about $8,000. Thanks to sponsors, Systems 2 and 3 have both been in the same approximate range, even though their complexity and actual value are orders of magnitude beyond the original. If you get involved with this project, I will try to help you find sponsors, but that can be an extremely time-consuming and complex undertaking that involves clear demonstration of what you can do for them.

What is your motive for all this, anyway?

Heh. I want company.

There’s tremendous energy in shared projects and community. For 10,000 miles I traveled alone, addicted to the energy of beginnings but gradually growing unsatisfied with them. There’s a lot to be said for established relationships, where you can draw on shared context to increase communication bandwidth.

For the next 6,000 miles I traveled with Maggie Victor, who has made a tremendous difference. She is my best friend, lifestyle maintenance manager, lover, partner, and business helper — but not a techie, hacker, or geek-generalist. Our group of two has not reached critical mass, and thus I still experience loneliness in many areas. On the road, this effect changes both positively and negatively: we meet a lot of people and some of them are absolutely fascinating, but we are still essentially a family of two — we both want more company, and for different reasons.

I attended the last couple of Hackers Conferences, and was intensely stimulated by the constant swirl of brains at play. There is powerful energy in a community of kindred spirits, and I want to combine that with the endless excitement of travel and life in the networks. I also want to make more money, which will be easier when a wider range of creative humans is right there in camp, sparkling with ideas and helping to support the whole operation.

That’s what’s in it for me. What’s in it for you?

What’s the timetable?

We’re planning to leave sometime in the summer of 1990, and it’s going to take heavy effort on everyone’s part to be ready by then. We’re working full-time on bikes and related projects (including the Journal) here in the Santa Cruz area (close to Silicon Valley, but not immersed in all the traffic and confusion).

Prior to departure, there will be a pre-launch assembly period during which we will all essentially live together while getting our systems fine-tuned and communicating. This will segue into an exhausting series of media events, many featuring our sponsors, and we will finally gather at the launch point for departure.

After that… it’s completely open-ended.

Assuming I want to do this, what are the first steps?

OK. Here’s your basic TO-DO list:

- Get a ham radio license and learn all you can about the technology and operating procedures. Buy a 2- meter handheld transceiver and get comfortable with repeater use.

- Buy a recumbent, start collecting bicycle touring gear, and practice traveling and camping.

- Get your body in shape, and not just your legs. No need to become a super-athlete — but you might want to take an aerobics class and do a bit of weight training. And ride your bike as much as possible!

- Devour the bicycle magazines and touring books (contact me for recommendations). Waste no opportunity to learn!

- Find out how to repair your bicycle, and assemble a toolkit.

- Save money, and open an account with a bank that supports a good network of electronic funds transfer machines.

- Pay off loans and otherwise simplify your life.

- Learn all you can about whatever it takes to run your business on the road, and start the conversion process now.

- Get a laptop, go online, and begin reducing your dependence on paper. Urge your major correspondents to do likewise, and use email as much as possible.

- Communicate regularly with me and everyone else who’s contemplating a life of nomadness. Call me now if you have specific questions or want to brainstorm the business options.

- Reduce clutter by converting unnecessary possessions to cash, and thence into tools for life on the road.

- Make a database of all your contacts here and around the world. Acquire directories (preferably machine-readable) of people who share your interests, club affiliations, alma mater, whatever.

- If you speak another language, brush up on it.

- Get your passport, credit cards, drivers license, insurance, association memberships, and any business-specific relationships up to date.

- Start a list of stuff you’ll need on the road. I can send you a complete inventory of my system and refer you to a couple of good published lists of recommendations for normal bicycle touring.

- Find a storage area for the stuff you’re leaving behind, but will probably want again someday.

Think, plan, and dream… then convert it into reality! See you on the road!!!

You must be logged in to post a comment.