Going Pro

Computing Across America, chapter 33

by Steven K. Roberts

Lake Livingston, Texas

May 23, 1984

Thanks for all the excitement!

The owner of the Cafe Texan in Huntsville, after I ate lunch there

Amazing what a book contract can do to you. In tiny Toomey, on the edge of Texas, I hung up the pay phone with a loud whoop and leapt out of the booth. I had just gotten a contract for this book.

My first excited thought was, “Damn, a publisher is really willing to pay me for this!” Somewhere in there, you see, I had been maintaining a flicker of face-saving doubt. Doesn’t a caper like this seem just a little too good to be true?

My second thought was, “Oh no! This is serious.” Hustling for a book contract and actually having to write the damn thing are two very different sensations. I have often felt that I should be somebody’s agent: the thrill of making deals would never be ruined by deadlines.

My third thought was, “OK, now I can justify the energy required to keep a decent journal.” The contract freshened my perception of the journey, and even as I leapt from the phone booth I began casting about the parking lot with a newly professional eye.

After I calmed myself with a beer and regaled my rather bewildered hostess with everything from the Sara Lee convict story to the subtle marketing considerations of nonfiction trade books in the evolving climate of Public Lending Rights, I returned to the pay phone. Naturally, I had to call the important people in my life and tell them the big news.

My mother was deeply concerned about the possibility of sexual content (moi?) and Kacy was cured of the flu in mid-sneeze. Walt said “Damn, Roberts, you really are going to pull this off, aren’t ya?” and Barbara beamed electronically in an impromptu online conference. My agent was ecstatic. “OK, we got it, Steve. Are you sure you can deliver by March?” Ask me in February.

And my Toomey hostess summed it up perfectly…

“Bubba!”

So I awoke the next morning on her living room floor and looked around. Everything seemed different, more detailed, somehow relevant. Hey, I was getting paid for this now: yesterday I couldn’t spell arthur; today I are one. It may only be six o’clock in the morning, but it’s time for research! Everything is copy.

I grabbed the journal and noted that the shelving on the west wall was full of those mirror tiles you find at state fairs — Mickey Mouse giving the finger, Charlie Daniels Band, Miss Piggy, a list of sex excuses, and so on. There were pictures of kids, a lava light, and a ceramic madonna. The cold water spigot in the bathroom was a pair of vise grips, and the cheese in the refrigerator was donated by the US Department of Agriculture. The stereo was made by Soundesign, and the clock was a backlit model advertising Budweiser Light. Those are the headlines.

I mean, hey, we got us a book contract! I brushed my teeth with a drilled-out Pro Flosser and a dab of Close-Up from a 1.4-ounce travel tube (OK, OK, I’ll stop now…) and then loaded the bike into my friend’s pickup truck. This would not have been my intent, but the local cops like to give cyclists $90 tickets for riding on the only available bridge across the mighty Sabine.

And then… TEXAS. I was in it.

I set out west from the drop-off point, expecting to make it all the way to Cleveland (the other one) by nightfall. But instead I experienced my shortest riding day of the entire trip: one mile. The sky grew furious, piercing the pseudo-dusk with sharp stabs of lightning and tearing from all sides with vigorous shifting winds. Then came the rain, intense and drenching. Campers stopped for gas, lights on, wipers slapping, their drivers sprinting with big Texas curses through the rare Texas downpour.

Rare is right. The “Golden Triangle” area had been in severe drought for many weeks, and the cracked, dusty fields were filled with miserable drooping beans. But seven inches fell on this sopping Saturday, and within the hour millions of tiny soygasms were rising in sweet chorus from the thirsty farms. The farmers began to drink and rejoice, and the rain continued. The soybeans drank their fill, and the rain continued; slowly the beans collapsed and lay dazed on the flooded ground. Still the rain continued. The beans drowned. The farmers got drunk and contemplated other career options.

I sprinted in momentary lulls from underpass to grocery store to motel, at last closeting myself in the sign-happy Ramada Inn of Orange, Texas.

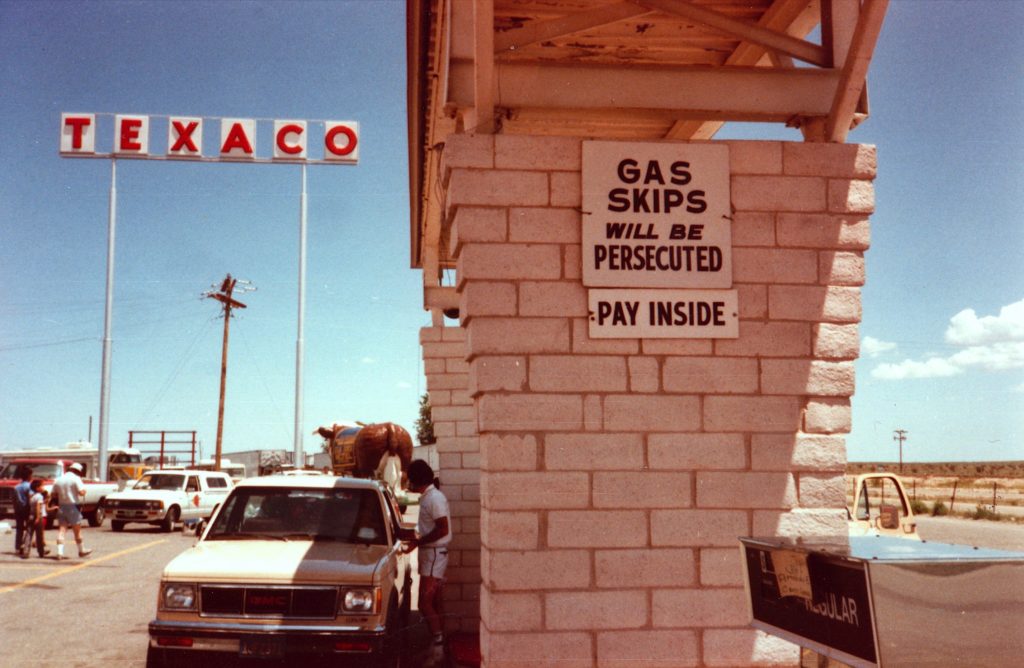

Over the front desk:

We reserve the right to refuse service to certain persons.

Over the ice machine:

Ice for guests only. Others will be prosecuted.

Under the shower massage:

Enjoy good clean fun.

Well, OK then. Sounds like a plan.

I signed on to the network via the room phone — that essential umbilicus of my electronic life. It was a gloomy Sunday afternoon in east Texas, and after getting the day’s mail I cavorted through the electronic halls of the vaporous network mansion, dropping in on parties and conversations as my fancy dictated. The Where U B? question was frequent but irrelevant; if you were on the network you were here. Period. This is a place that is everyplace at once.

Simone and I met in a laid-back free-for-all of online small talk and gossip, developing mutual curiosity as people materialized and winked out around us. It was as if we were caught in the grip of a Star Trek transporter gone berserk — milling about in a cosmic cocktail party of constantly changing faces. She appeared beside me just as I was bidding farewell to a fading Farquor; resplendent in her network finery she popped into view and cried, “Wordy! I just read your sailing story five minutes ago! Where are you now?”

“Orange, Texas,” I replied. “You?”

“Howdy, neighbor! I’m in Houston!”

I gave her a <tentative hug> across the mere hundred miles that physically separated us, and within minutes we had politely excused ourselves and established the private /talk link. A visit? Well, uh, why not? I gave her directions to my motel, and paused for a moment in the virtual certainty that this was insane. What was I getting into? She was skipping a friend’s birthday party to come here, and there were two realities involved — the physical reality of a motel room and the network reality of teasing electronic chitchat. I wasn’t entirely sure I wanted to try mixing them.

Recalling Tina/Dave, I shook my real head while smiling invitingly with the imaginary one.

And three hours later she was there, smiling pretty in my doorway with a computer under her arm. “I brought this,” she said, holding up the portable computer, “just in case we don’t get along face-to-face. We can hook our machines together and play online.”

But surrogate interfacing turned out to be unnecessary. Ain’t technology wonderful?

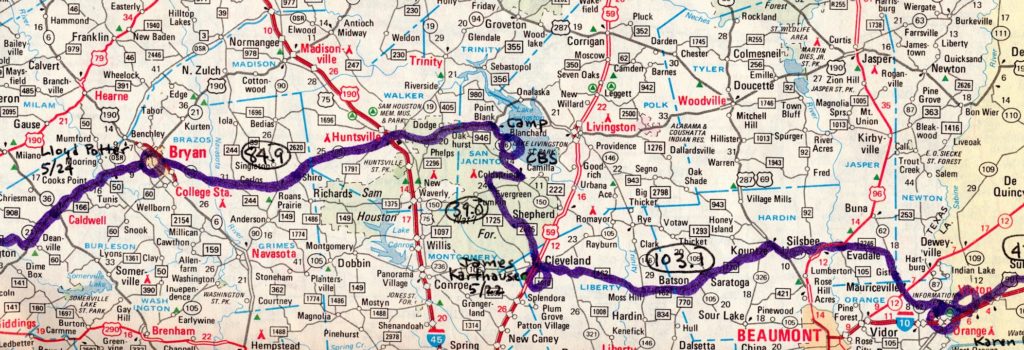

My first century! The macho cyclists would have approved, although for them it was probably routine: 103.1 miles in one day.

This whole end of Texas struck me as dramatically different from the lands I had just crossed. Few passing drivers smiled, waved, or even turned to look. It wasn’t hostile at all, just neutral — although a group of high-school kids in the Silsbee Pizza Hut were fairly hopping with questions. The biggest one seemed to be, “Man, what are you doing in Silsbee?

I walked outside and found a fellow smirking at the bike and shaking his head. As I stepped aboard, he laughed derisively and said, “Hell, that ain’t gonna work! Can’t balance it.”

I fastened my helmet and snapped the kickstand into its clips on the top tube, then looked at him in mock alarm. “Oh no… you mean, after riding all the way from Ohio, I’m stuck here?” I grinned and pushed off with a wave.

“Well, I’ll be dipped.”

An even better quote happened later that day. I had stopped in some little town, and a guy asked where I was headed. “California,” I told him. “then probably back across the northern US.”

“Aw shit, you’re crazy. It’s uphill all the way!”

“Well, it’s up and down—“

“Yeah, you’ll go downhill sometimes. But even when you do? You’re gainin’ elevation.”

I thanked him and coasted uphill. The land alternated between rolling and flat, carpeted with piney woods and roadside daisies. There was a sense of vastness, but some of that was psychological (after all, we’ve been hearing since infancy that Texas is BIG).

It’s also culturally diverse, surprisingly so. The state is checkerboarded with extremes in liquor laws, religions, ethnic backgrounds, and levels of awareness — with matters technical covering the entire range from the high-tech oasis of Austin to a high school in Cleveland where the principal refused to start a computer program in 1983 because “computers are just a fad.”

Then I picked up an entourage: a crew of four from CBS Morning News, led by Norm Glubok, the producer. Smooth, relaxed and professional, they knew how to capture moments of my traveling life without putting me too obviously on the spot.

In Coldspring, I stopped for lunch at a restaurant called Kimon’s. Meringue pies four inches tall stood in glass-front coolers; at every table people enthusiastically gobbled ample piles of country cookin’. I ordered something big and juicy, with the wireless microphone still transmitting under my wet T-shirt.

I watched the crew unpack in the hot sun and carry in the equipment. Now people were openly gaping — at the bike, at the strangers from CBS, at the cameras, at me. The sandwich arrived and I bit into it while the great unblinking eye of a $35,000 video camera stared into my face, the warm trickle of sauce filtering into my beard being recorded as clearly as my sweat-matted hair. I wiped my mouth self-consciously. Is nothing sacred?

The crew and I leapfrogged our way on to Lake Livingston: every few minutes I would round a bend to see their tripod-mounted camera staring as I rose from the shimmering heat waves of Texan asphalt. It would pan smoothly as I passed, and then they’d pack the equipment into their van and race past me with a honk and a wave to do it again. And again. And again.

By evening, we had reached a campground on the shore of Lake Livingston and they sped away to a Huntsville motel, leaving me unscrutinized for the first time all day. At last I could pick my nose and make rude noises.

Wolf Creek Park was sparsely populated, and the lake — only a few mosquito-filled feet from my tent — placidly reflected the pastel blue-peach of a hazy sunset. There were the sounds of birds and a single distant motorboat; fishermen a few campsites away popped open the occasional beer and pocked the water with gracefully flung lures.

I sat at my picnic table, staring at the atlas as the sun faded: five thousand miles exactly.

Zip. Zip. Zip. Swat. Swat, damn it, swat. Snore.

And then uproarious peals of pre-dawn laughter. Huuhh? I dragged open aching eyelids and tried to figure it out. Nothing is funny at this hour. I stretched, fortunately somewhat dressed, and looked out the tent’s screen door into that unblinking eye again, sitting on its tripod under a softly glowing sky, watching me wake up.

(Three months later on national television, I would watch myself crawl bleary out of the tent with a serious case of bed-head, plopping heavily on the picnic table to contemplate a too-early sunrise. This is very strange. I had suspected the possibility of becoming sort of public, but…)

Oh yes, the laughter. The CBS crew consisted of the producer and correspondent from New York, assisted by a two-man camera team from their Houston affiliate. One of the latter was treating the others to a uniquely Texan phenomenon known as the Aggie joke. Aggies are students at Texas A&M in College Station, and most jokes of the genre are just typical ethnic jokes with a local twist. But some of them incorporate that punchline context-switch that underlies the finest humor.

An Aggie done got hisself admitted to Harvard, thanks to his father’s money. On his first day there, he was walkin’ around campus, trying to get his bearings.

He stopped another student, and in his slow Texas drawl asked, “Uh, pardon me there fella, can yew tell me whar the Lamont lahbary’s at?”

The upperclassman looked down his nose at the Aggie, and replied in a proper Bostonian accent: “Look, I have no idea who you are or whence you came, but people here do not end sentences with prepositions.”

The Aggie thought about this for a moment, then tried again: “Well awright. Can yew tell me whar the lahbary’s at, asshole?”

Once I was awake enough to be articulate, we began the interview. I sat at the picnic table across from Martha Teichner, discussing the hows and whys of my nomadic lifestyle. I spoke in colorful detail about the wonders of the network world, at last prompting Norm to call “Cut! I can’t use that.”

I was taken aback by his directness. “Uh, what’s the problem?”

“Too convoluted. You’re referring back to things you said five minutes ago and telling us about things you’ll be talking about in a moment. We can’t edit that!”

“Well, I’ll try to keep it tighter.”

He grinned. “I want thirty-second speech bites, ending on a downward inflection with your mouth closed.”

“I’ll see what I can do.” I was unsure now, my hyperloquacity no longer a defense against on-camera nervousness. But if this was indeed to become a professional venture, I’d have to learn eventually. I tried again, too tense; I tried again, too terse. And then I tried yet again, dully, sick of saying the same things over and over.

“It’s not just an adventure, it’s a job!” I finally declared. “I’m doing business with a portable computer and worldwide communications networks while living on a bicycle. This journey is the ‘electronic cottage’ carried to an extreme — I have broken the chains that once bound me to my desk and am now free to wander forever if that’s what I want to do.” I gestured at the morning lakeside woods. “This is my office.”

“That’s a take.”

And then we were off, riding once again through the hilly expanse of my office, spooking a white-faced horse and stopping to chuckle at fourteen large turtles standing like a subdivision of domes beside a placid farm pond. My CBS friends bid me farewell and returned to New York with their video caricature of my life, and I moved on through Aggie country, grazing country, oil country — the famed playground of Austin only two or three days away.

The slowly reciprocating oil wells somehow fit perfectly into my office decor. I thought of them as executive toys, real-life versions of those mail-order gadgets that people buy to add fantasy to a deskbound lifestyle.

“Take a letter!” I cried to a ruminating cow. And damned if she didn’t wink at me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.