On the Loose in Dataspace

This article is a bit of a treasure in the timeline of BEHEMOTH. Published in the premier issue of Marlow RFD (subtitled “Motherboards and Apple Pie”), this was a 2-page spread that captured the insane, driven passion behind the extravaganza of geek obsession that was this final version of the bike. For three years I had been at it, and at this writing I was in the final departure countdown in the Bikelab hosted by Sun Microsystems. Every day, volunteers from around Silicon Valley would converge, sharing the dream and building marvelous things, but rarely did I take a break from the madness to step back and ask WHY I was still at it after 16,000 miles and eight years of hard work. Despite well-practiced sound bites about nomadic connectivity and freedom, it had been a long time since I dreamily sketched the underlying motive. But here, in this rather obscure publication, they were laid out clearly.

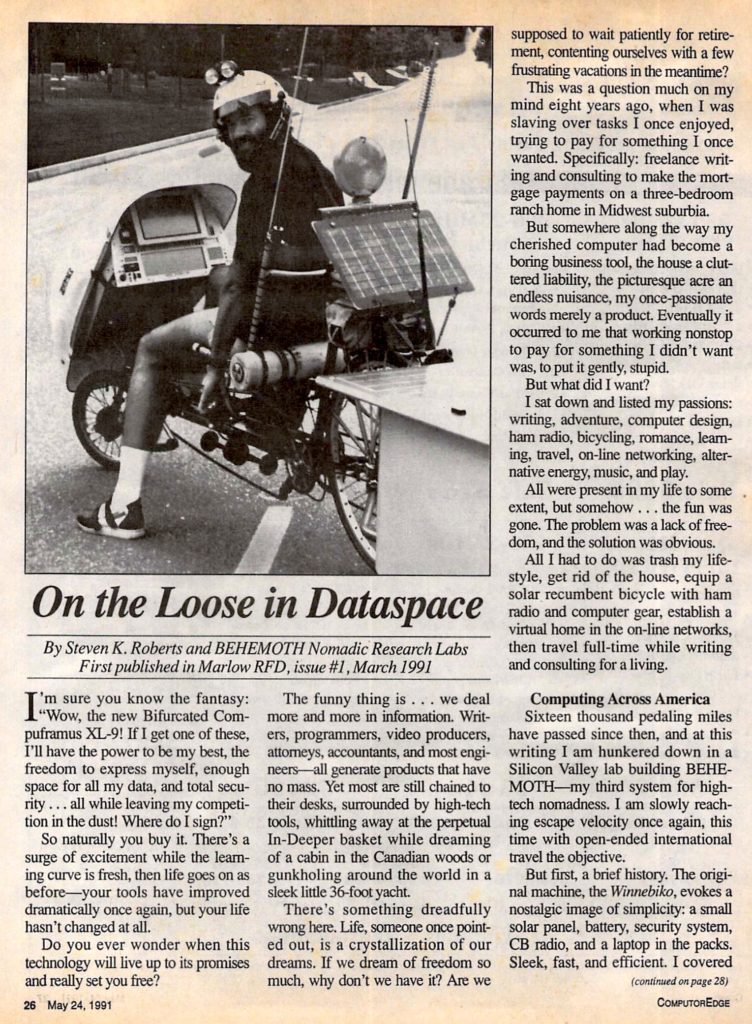

(Photo above in Eureka is by Tom Forsyth. The article also appeared a couple of months later in ComputorEdge, and the scan appears at the end of the Marlow version.)

by Steven K. Roberts

Nomadic Research Labs

Marlow RFD

March, 1991

I’M SURE YOU KNOW the fantasy: “Wow, the new Bifurcated Compuframus XL-9! If I get one of those, I’ll have the power to be my best, the freedom to express myself, space for all my data, and total security… and leave my competition in the dust! Where do I sign?”

So naturally you buy it. There’s a surge of excitement while the learning curve is fresh, then life goes on as before — your tools have improved dramatically once again, but your life hasn’t changed at all.

Do you ever wonder when this technology will live up to its promises and really set you free?

The funny thing is… we deal more and more in information. Writers, researchers, teachers, programmers, stackware authors, video producers, musicians, CAD system pilots, attorneys, accountants, and most engineers — all generate products that have no mass. Yet most are still chained to their desks, surrounded by high-tech tools, whittling away at the perpetual IN-DEEPER basket while dreaming of a cabin in the Canadian woods or gunkholing around the world in a sleek little 36-foot yacht.

There’s something dreadfully wrong here. Life, someone once pointed out, is a crystallization of our dreams. If we dream of freedom so much, why don’t we have it? Are we supposed to wait patiently for retirement, contenting ourselves with a few frustrating vacations in the meantime?

This was a question much on my mind eight years ago, when I was slaving over tasks I once enjoyed, trying to pay for something I once wanted. Specifically: writing and consulting to make the mortgage payments on a three-bedroom ranch home in Midwest suburbia. But somewhere along the way my cherished computer had become a boring business tool, the house a cluttered liability, the picturesque acre an endless nuisance, my once-passionate words merely a product. Eventually it occurred to me that working nonstop to pay for something I didn’t want was, to put it gently, stupid.

But what did I want? I sat down and listed my passions: writing, adventure, computer design, ham radio, bicycling, travel, music, on-line networking, alternative energy, and play. All were present in my life to some extent, but somehow, the fun was gone. The problem was a lack of freedom, and the solution was obvious.

All I had to do was trash my lifestyle, get rid of the house, equip a solar recumbent bicycle with ham radio and computer gear, establish a virtual home in the on line networks, then travel full-time while writing and consulting for a living…

Sixteen thousand pedaling miles have passed since then, and I am now hunkered down in a Silicon Valley lab building BEHEMOTH — my third bicycle system for high-tech nomadness. I am slowly reaching escape velocity once again, this time with open-ended international travel the objective. What began as a fancy getaway has evolved into something quite deliciously mad.

But first, a brief history. The original machine, the Winnebiko, evokes a nostalgic image of simplicity: a small solar panel, battery, security system, CB radio, and a laptop in the packs. Sleek, fast, and efficient. I covered 10,000 miles solo, Ohio to the East Coast, down to decadent Key West, across the country through Texas, throughout the western slopes of Colorado, down to southern California via COMDEX, and up the Pacific Coast to the Bay Area. Romance, adventure, wild craziness… it all yielded a book called Computing Across America, a virtual flood of magazine and online columns, and an endless succession of entertaining on-the-road contacts.

One big problem, though: I couldn’t write, or do much of anything else, while riding. Every 10,000 miles takes about 1,000 hours of pedaling time, and that’s half a business year. I’m a struggling free-lance writer, not a rich American traveling the world. It was fun, but from a steely-eyed business perspective, the numbers were disastrous.

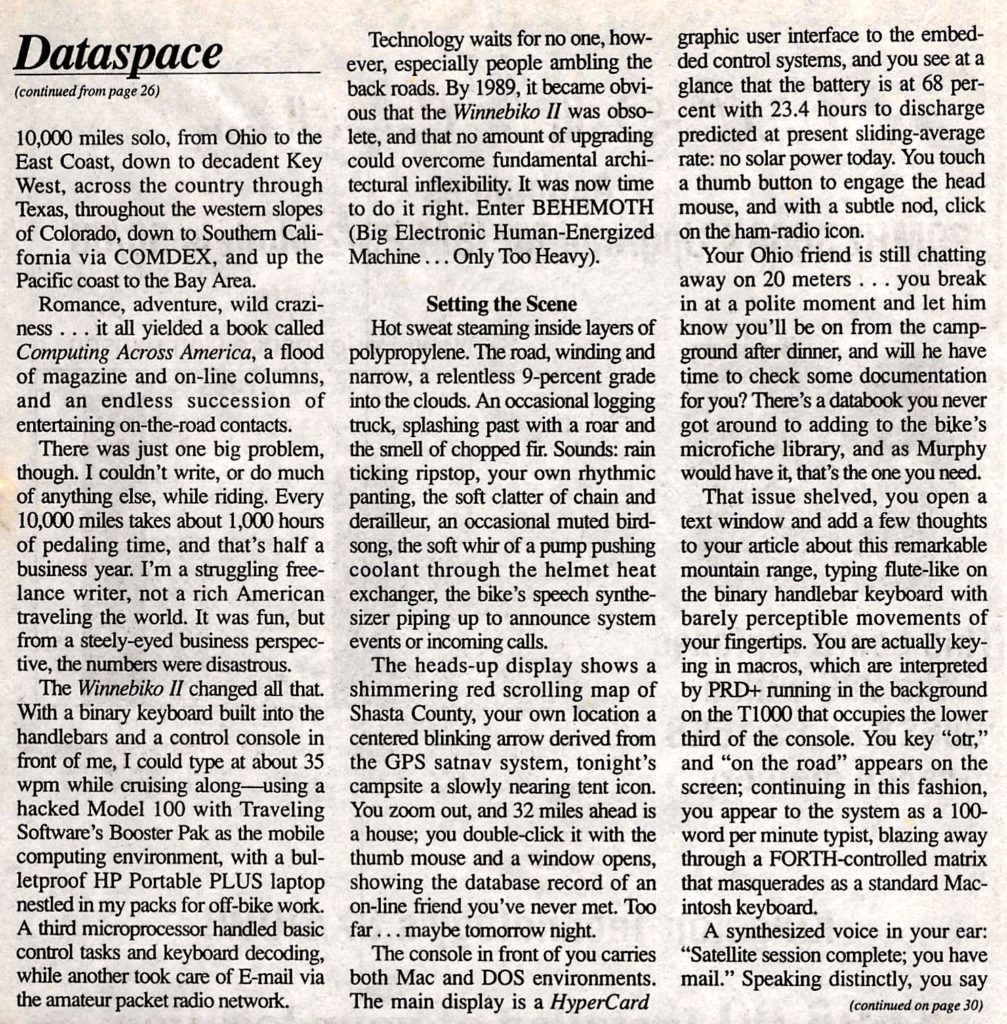

The Winnebiko II changed all that. With a binary keyboard built into the handlebars and a control console in front of me, I could type at about 35 wpm while cruising along — using a hacked Model 100 with Traveling Software’s Booster Pak as the mobile computing environment, along with a bulletproof HP Portable PLUS laptop nestled in my packs for off-bike work. A third microprocessor handled basic control tasks and keyboard decoding, while another took care of E-mail via the amateur packet radio network. I went from 5 to 20 watts of solar panels, upgraded from 18 to 54 speeds, added a cellular phone and 2-meter ham radio, and hung a trailer off the back to increase load-carrying capacity. (At its peak, this system reached 275 pounds.)

And there were other changes as well — while the book was populated with an intoxicating succession of on-the-road romances, I was beginning to sense the need for something other than exuberant beginnings and bittersweet endings. A few months before launch, Maggie Victor entered the picture, responding to my innocent invitation to “go for a bike ride” by trashing her own life-style and moving to a second recumbent. With GEnie as our electronic hometown, we hit the road together in ’86 — covering 6,000 miles in a shared adventure along both coasts.

Technology waits for no one, however, especially people ambling the back roads. By 1989 it became obvious that the Winnebiko II was obsolete and that no amount of upgrading could overcome fundamental architectural inflexibility. It was now time to do it right.

Enter BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine… Only Too Heavy).

I suppose the first issue, before establishing a basic design specification, is why. Has high-tech nomadness become an addiction, the habitual peregrinations of an aging yuppie hobo? What else but addiction could motivate me to concentrate all available resources into a 350-pound million-dollar machine, just to expose not only it but my own fragile body to the violent drunken terrors of the highway?

I have a whole armamentarium of carefully formulated reasons, but I’ll spare you. Just this: the bottom line is fun, and I mean that very seriously. (Success, after all, is the ratio of all you put out to all you get back. Who says it has to be measured in dollars?) And if the whole thing still seems like the obsessive hacking of a tripped-out West-Coast silicon junkie who never quite escaped the ‘sixties, imagine yourself in this scenario:

Hot sweat, steaming inside layers of polypropylene. The road, winding and narrow, a relentless 9% grade into the clouds. An occasional logging truck, splashing past with a roar and the smell of chopped fir. Sounds: rain ticking ripstop, your own rhythmic panting, the soft clatter of chain and derailleur, an occasional muted birdsong, Maggie’s voice breathless in your ear via 2-meter ham radio, the soft whir of a pump pushing coolant through the helmet heat exchanger, the bike’s speech synthesizer piping up to announce system events or incoming calls.

The heads-up display shows a shimmering red scrolling map of Shasta County, your own location a centered blinking arrow derived from the GPS Satnav system, tonight’s campsite a slowly nearing tent icon. You zoom out, and 32 miles ahead is a house; you double-click it with the thumb mouse and a window opens, showing the database record of an online friend you’ve never met. Too far… maybe tomorrow night.

The console in front of you carries both Mac and DOS environments. The main display is a HyperCard graphic user interface to the embedded control systems, and you see at a glance that the battery is at 68% with 23.4 hours to discharge predicted at present sliding-average rate… no solar power today. You touch a thumb button to engage the head mouse, and with a subtle nod click on the ham radio icon. A virtual front panel pops up, looking remarkably like the Icom HF transceiver back in the trailer — with a click of another button it comes to life, while below your awareness a trio of FORTH processors in the bike’s major nodes set bits in their audio crosspoint switch matrices to establish a bidirectional audio link between radio and helmet. Your Ohio friend is still chatting away on 20 meters… you break in at a polite moment and let him know you’ll be on from the campground after dinner, and will he have time to check some documentation for you? There’s a data book you never got around to adding to the bike’s microfiche library, and as Murphy would have it, that’s the one you need.

That issue shelved, you open a text window and add a few thoughts to your article about this remarkable mountain range, typing flutelike on the binary handlebar keyboard with barely perceptible movements of your fingertips. You are actually keying in macros, which are interpreted by PRD+ running in the background on the T1000 that occupies the lower third of the console, “otr” you key, and “on the road” appears on the screen; continuing in this fashion, you appear to the system as a 100+ word-per-minute typist, blazing away through a FORTH-controlled matrix that masquerades as a standard Macintosh keyboard.

A synthesized voice in your ear: “Microsat pass complete; you have mail.” Speaking distinctly, you say “Read it” into the microphone; the Covox interprets the command and the Audapter immediately reads you a friendly note from a woman in Australia, ported from Internet via a SparcStation in Silicon Valley.

Another logging truck, too close! You touch a red thumb button and the air horns blast — the driver swerves and toots back. Grrr.

The road levels, the rain finally stops, and it’s a downhill coast all the way to camp. Occasionally you squeeze the brakes, but never quite enough to engage the hydraulics — the bicycle control processor senses the pressure rise in the system and directs the regenerative braking controller to draw a proportional amount of power from the variable-reluctance front wheel hub. This satisfies your braking requests and dumps a couple hundred watts into the power bus. Today it recharges the batteries. On a sunny day, the excess power would be passed to the solid-state refrigerator that cools the thermal mass of drinking water, providing a heat sink for your helmet cooler. It feels good to conserve scarce resources.

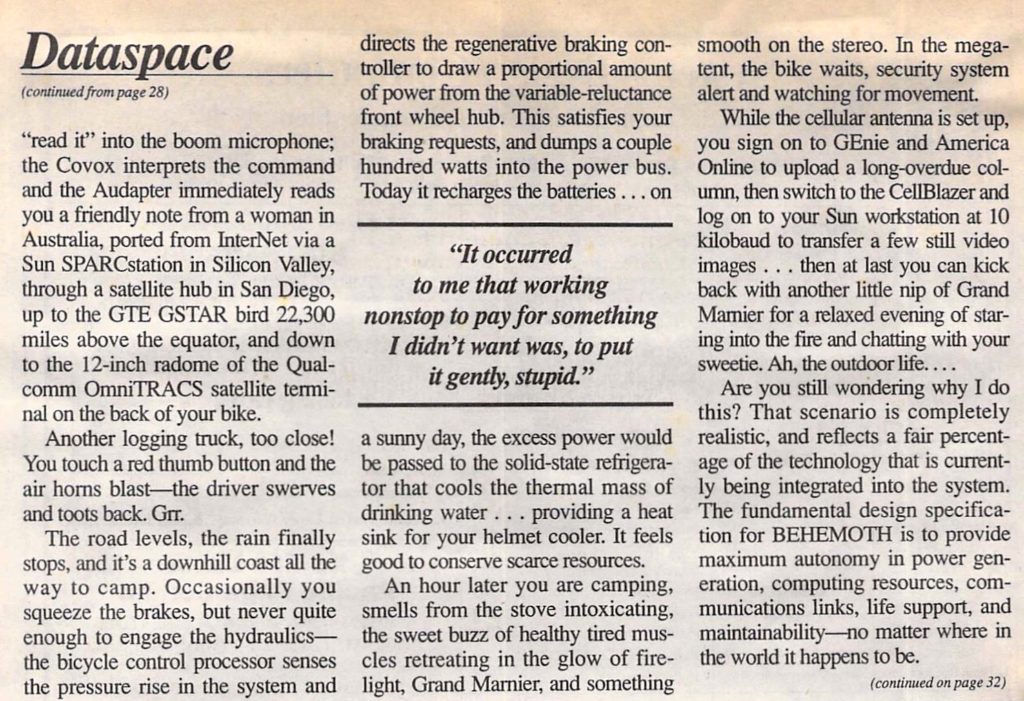

An hour later you are camping, smells from the stove intoxicating, the sweet buzz of healthy tired muscles retreating in the glow of firelight, Grand Marnier, and something smooth on the stereo. In its own tent the bike waits, security system alert and watching for movement. You can’t relax yet, though — you have to consult an orCAD file prior to the sked with the ham in Ohio. You climb into your tent, and under candlelight open an aluminum suitcase, flip up a small antenna, touch a key to awaken the laptop, and sign on to the bike via UHF business band packet datacomm. A few quick commands, and you hear the Ampro 286’s hard drive quietly spin up off in the trees — then the file enters your local system RAMdisk in short 4800-baud bursts. While munching linguini with clam sauce, you peruse the schematic and make a few notes.

Once you get the pinout data from Ohio and finish the changes to the CAD file, it’s time to ship it to your partner on the design project. The final version will go out machine readable direct to the printed-circuit fab house, of course, but this one is for comments. You extend the fiberglass BYP (big yellow pole) mounted on the back of the trailer, aim a six-element 900-MHz yagi antenna in the general direction of Redding, and via the laptop RF link direct the system to check for clear cellular phone service. That established, you pass a print capture of the schematic file to the fax software and let the bike handle the details of sending it to a fax machine in Boston.

While the cellular antenna is set up, you sign on to GEnie to upload a long-overdue column and get the mail, then kick back with another little nip of Grand Marnier for a relaxed evening of staring into the fire and chatting with your sweetie. Ah, the outdoor life…

Are you still wondering why I do this? That scenario is completely realistic and reflects a fair percentage of the technology that is currently being integrated into the system. The fundamental design specification for BEHEMOTH is to provide maximum autonomy in power generation, computing resources, communications links, life support, and maintainability — no matter where in the world it happens to be.

So what’s the point?

BEHEMOTH erases all boundaries between work and play. It eliminates geographical location as a factor in maintaining effective relationships. It embodies a suite of technologies that collectively offer dizzying freedom. And, as I said earlier, it’s fun.

But perhaps most provocative is what the bike’s technologies imply for future lifestyles in general. If it’s not obvious already, I am basically just BEHEMOTH’s project manager — most of the wizardry has emerged from the labs of the more than 150 companies that have made this system possible, and it’s on the market now. The Mac Portable, Ampro single-board industrial DOS systems, New Micros low-power FORTH boards, the Private Eye display, Etak maps on CDROM, Solarex solar panels, efficient networks, cellular modems, improved battery chemistry, tiny RF data links…the list goes on and on. If any grandiose purpose can be claimed for the bike, it is the public integration of widely diverse technologies that usually appear in vertical target markets.

What do these technologies imply? Freedom from traditional limits. Now in the marketplace are products that allow a radical change in the way we live. It no longer matters where you are, and information (the essence of most business) weighs nothing and moves at the speed of light.

Perhaps those desk-bound dreams of escape aren’t so remote after all…

ComputorEdge version

This article also appeared in the San Diego computer magazine on May 24, 1991. The text has been slightly tightened, and the scans are below:

You must be logged in to post a comment.