Computing Across America – Epilogue

by Steven K. Roberts

Humboldt County, California

January 14, 1987

Two years have passed. While this book has been held up at every turn like an unsuspecting foreigner in the wrong part of New York City, I have rolled on. I write now while pedaling along a wooded bike path, playing the handlebar keyboard like an electronic text-flute as words form on the screen before me. A quarter of a mile back, linked to me by two-meter ham radio, is Maggie Victor — my recumbent-borne cyclemate. I touch a handlebar button and say hello; her voice tiny in my ear asks, “How’s it going up there?”

“Fine,” I say. “I’ve decided to work on the epilogue. Watch out for this broken glass.”

A lot has changed.

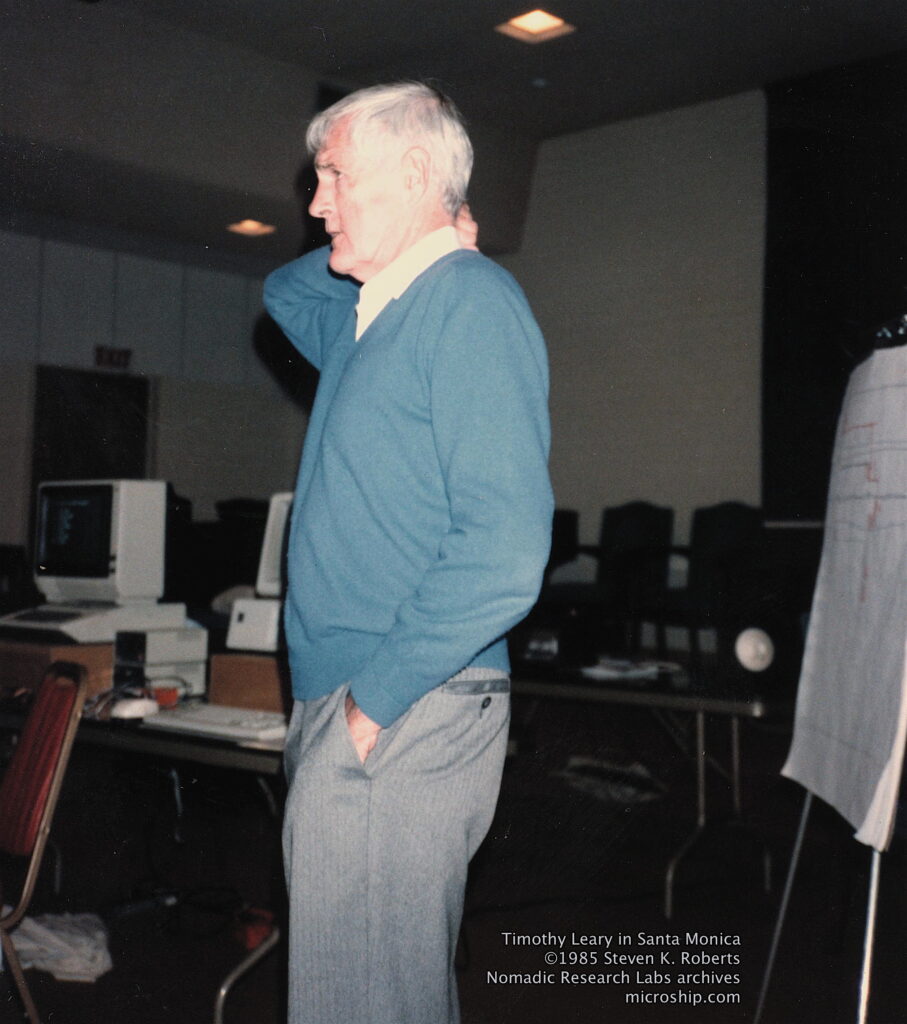

The Casa de Ha-Ha is far behind me, two years and a lifetime in the past. I have resumed my multisensory carom through the American scene; daily change is again my way of life. I emerged from the shadows of California’s Orange Curtain and watched Los Angeles roar by like a hundred-mile suburbia, edged with offshore oil rigs and blanketed in two-pack-a-day smog. In Santa Monica I shared a podium with Timothy Leary for an afternoon; between Malibu and Oxnard, a spirited lady pulled over, handed me Isham’s Vapor Drawings tape, and joined me for a night of camping. And the haven of playful understanding known as Santa Barbara touched me like an expert lover — triggering mad thoughts of permanence until yet another succession of enchanting encounters lured me inexorably up the coast.

Ah, the coast! That long-awaited California mystique came out of hiding at last, joining the Other Woman in a 400-mile seduction that left me panting from more than just the hills and headwinds. There was beauty on every level — from the grins of fellow cyclists to the rhythmic barking of cliffside seal colonies, from the deep folds of Highway 1 to the dollar-a-night campgrounds scattered along it, from the nepenthean microculture of Big Sur to the lustful beaches of Capitola. I pedaled slowly north, savoring the raw sensuality of my traveling life and wondering if I would ever be capable of ending it.

Indeed, that became the issue as I neared San Francisco and the magic 10,000-mile mark. I thought back to the beginning, back to those early speculations about why I was doing this. It had started simply, you recall — a fancy getaway, a madcap adventure, a flirtation with that sweet piece of asphalt called the Other Woman. I remembered the discussions about freedom versus security, all those earnest attempts to invent philosophical underpinnings for my new life of play… and I realized that travel had become my default mode, the road my equivalent to living room walls. I was indulging an addiction to movement — living a life without commitment and getting high on the energy of beginnings.

In the middle of agonizing about “what next,” I rented a van and drove back to Ohio — intent on staying only long enough to do the final edit on this book (which, to paraphrase Churchill, had by then evolved from mistress to master to tyrant). I should have recognized the dulling haze for the harbinger that it was and turned around somewhere near Phoneton, but instead I moved in with an old girlfriend — out Marysville way where the men wear Jack Daniels caps.

The visit was to have been only that — a way to repair the faltering business structure, finish the book, and earn a little consulting money before returning to the road. But hunger has a way of diverting dreams: I found an almost embarrassingly high-paying job, stopped thinking about the bike, started working with optical disk systems, and let myself enjoy the unfamiliar illusion of financial comfort. My parents sent me a hand-tooled pigskin business-card case, delighted that I had finally stopped being a bum.

I bought a TV and a stereo, rented a suburban apartment complete with athletic club membership, and hauled the Winnebiko up to the spare bedroom as a showpiece for guests. The journey — that energetic highlight of my life — began to seem a sort of fantasy, a dim memory of another epoch. I carried the book’s cover photo around in my wallet and, like a grandparent, pulled it out much too often.

But Ohio winters have a way of touching everything with gray misery, and as I sat at the corporate desk pondering the implications of my newfound yuppiedom one afternoon in 1986, I knew what had to be done. Fingering my yellow tie and squirming my toes uncomfortably in new leather shoes, I remembered the freedom, the country roads mottled with sun and shade, the smiling eyes of new friends, the energy of endless beginnings, the taste of beer after a hundred miles, the views from mountaintops, the sand under my feet… the road.

I looked down at the interactive videodisc PROLOG software I had been writing and found a rough sketch of a recumbent bicycle.

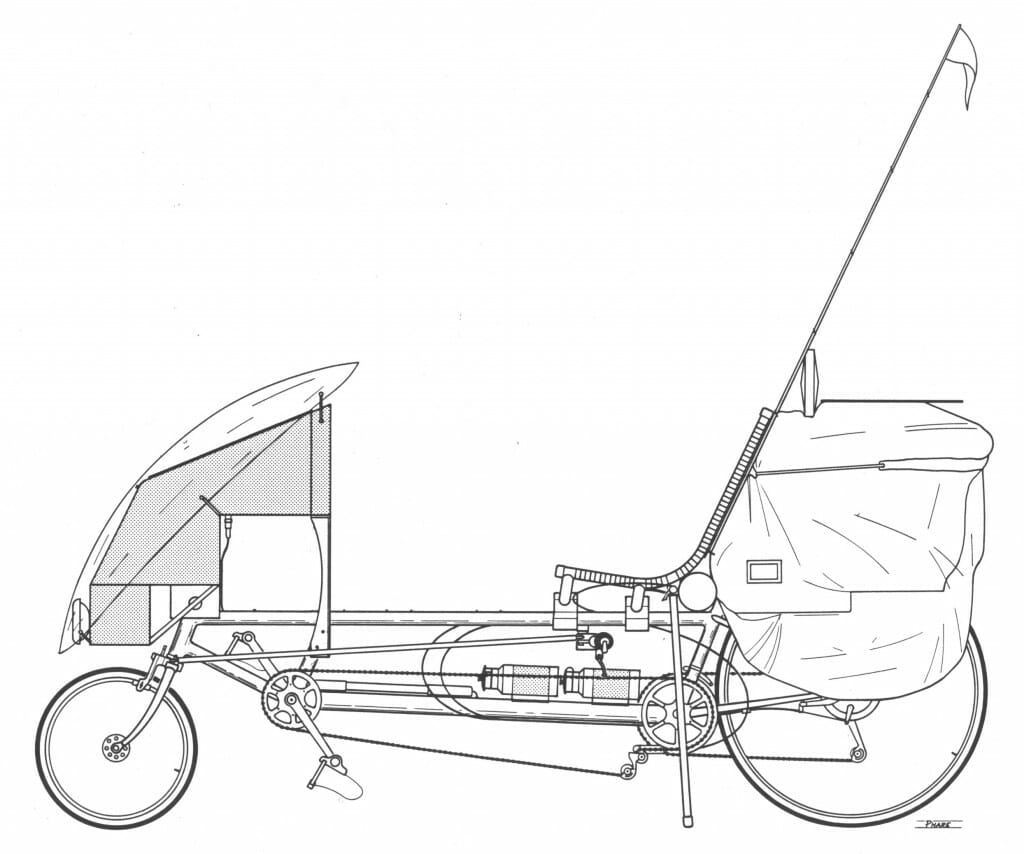

In a rush, purpose came flooding back. Energized, crazy, I spent the next eight months building the new system — motivated by the realization that I needed a way to write while riding, to capture thoughts in an electronic web and save them for later processing.

This is anything but frivolous. The biggest problem during the first trip involved time management (something that affects nomads as much as it does executives). I had spent roughly half a business year pedaling — a thousand hours sitting alone on the bike. I would cruise solo all day, composing tales in my head and itching to get my hands on the H-P Portable riding behind me. (“Ah, such a chapter shall this be!”) But by evening I would be tired and hungry and surrounded by people clamoring for stories… and the ideas would drift away like the smells of camp cooking, gone without so much as a memory of the insights that had spawned them. Wasted.

And so the bike has become a rolling word processor. There are five liquid crystal displays on the console, and eight keys built into the handlebars (offering 255 combinations). A dedicated microprocessor watches the keyboard while attending to other bicycle management tasks, decoding finger patterns and passing them on to a second system that takes care of editing, file management, communications, idea processing, and so on. At the end of a riding day, it is a simple matter to plug in a cable and transfer text from the bike to the 1.2-Megabyte Portable PLUS back in the trailer.

But it doesn’t stop there. A fourth computer is dedicated to speech synthesis, allowing the bike to explain itself to onlookers or intone “Please do not touch me” in a robotically threatening voice when the security system is triggered. And a fifth system handles packet data communication, allowing me to send and receive electronic mail from just about anywhere — phone or no phone, even while pedaling.

There’s more still. A Yaesu multimode 2-meter ham radio allows me to make phone calls from the road, as well as connect with the amateur community in passing towns (N4RVE here, pleased to meetcha). Air horns give me the acoustic demeanor of a Big Rig; 54 gears let me accelerate like one. Disc and hydraulic brakes take care of that ever-critical stopping problem, and twenty watts of solar panels have replaced the original five. The whole system (with trailer) now weighs 275 pounds and, amazingly, feels comfortable… even though my power-to-weight ratio is roughly that of a three-horsepower lawnmower engine pushing a three-ton mini-motorhome.

Yes, everything is different: the first bike seems almost primitive by comparison. But there are other changes that have nothing to do with technology.

Maggie and I met in a jazz bar, back in Columbus — making eyes through smoky haze as articulate guitar riffs filled the air. Our first conversation was touched with that portentious awareness of Something Significant, and it took but days for serious romance to set in.

“How would you like to go for a bike ride?” I asked her a few weeks later.

“That sounds delightful.”

“OK… quit your job, sell your car, trash your lifestyle, move in with me, buy a recumbent, study for your ham license, and get in shape. We leave in August.”

And that’s exactly what happened. We’re now 4,000 miles into our first date: we drove to Vancouver, displayed the bikes at Expo, then pedaled slowly down the coast, stopping for weeks at a time to explore and touch the magic. This extended ménage à trois with the Other Woman is my latest technique for having both freedom and security at once: in these declining years of the sexual revolution, as the singles world reels with AIDS paranoia, it’s deeply refreshing to have one stable intimate relationship. This is a radical change from the first trip… it’s the pathogen not taken.

And hitting the road was like going home.

Sometimes Maggie and I hole up for a while and contemplate the options. More cycling? A sailboat? A recumbent kayak? An ultralight aircraft? A high-tech micro-motorhome? Interesting: all the choices are based on movement. Once your neighborhood becomes global and movement the norm, staying in the same town all the time is like staring out the living room window, hoping that someone wonderful will have car trouble and knock on your door to use the phone. (I was like that once, long ago, even inviting the UPS man in for coffee when the loneliness became too crushing.)

But now our neighborhood is thousands of miles across. We prowl it endlessly via satellite and bicycle — learning, teaching, sharing, growing. There is no end in sight, only an occasional change of style as the information-handling tools grow ever more exquisite, as the globe shrinks further…

With the digital shortwave receiver we hop around the world from our megatent, reminded with every cruise across the spectrum that Moscow is only five keystrokes away from Washington; that Iran, Nicaragua, and South Africa are clustered together just down the road from the voice of Time itself.

One world.

New electronic keys into the thickening web of global information give us same-day mail service into any major city on the planet. Tokyo is now not much more remote than Columbus.

One world.

Through the ham radio, we can make phone calls from cornfields, highways, and campsites in the Sierras; through the terminal node controller, we can access mailboxes both terrestrial and orbiting… sending a message to a friend in Sweden while rolling down the road.

One world.

I’m riding a multi-megabyte Winnebiko with dozens of communications options, and more wonders lie just ahead: a lightweight satellite link, maps and reference books on CD-ROM, wide-bandwidth networking… it is no longer very difficult to be a deeply involved, productive citizen of the world while wandering endlessly.

Because once you move to Dataspace, you can put your body just about anywhere you like.

How better to spend a life? Combining all my passions; sharing a high-tech adventure with a lady I love while the Other Woman plies me with the rich experiences of present delights and future books. And I’m now riding the magic window, my electronic portal to the not-land of Dataspace. It’s my ticket home.

See you online, neighbor.

The End

You must be logged in to post a comment.