Life and Death

Computing Across America, chapter 41

by Steven K. Roberts

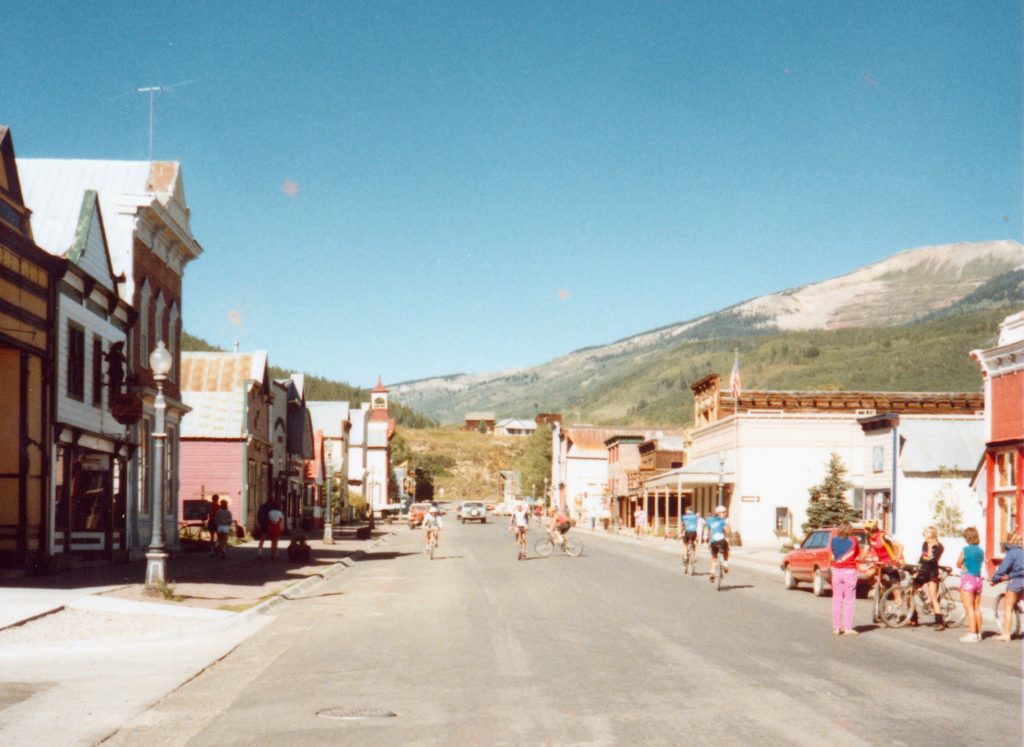

Crested Butte, Colorado

September 5, 1984

There’s never enough time to do all the things you don’t have to do.

Anita Simon

It’s startling to stumble depressed into a strange town, expecting nothing, knowing no one, and find there a home. Homes are usually things that grow over time — emerging like well-tended gardens from the rich soil of friends and familiar possessions. But here and there are special places that wrap around your psyche and coddle your body, enforce your comfort and bid you stay.

Such places fit like a cozy old couch, and finding them is at once the lure and the ultimate demise of travel.

Crested Butte was almost a shock. It is a land of play: people don’t end up in the Butte by accident — they go there because they love it. They go there, and then they stay there, season after season, year after year, caught up in a “play ethic” so pervasive that no day is ever considered complete without some form of recreation. Such a lifestyle naturally fits me like the seat of my rolling home, and I moved from my bike-a-lounger to the La-Z-Butte Recliner without the slightest hint of tire itch.

Of course, this is a hard-core bicycle town — that might have eased the transition a bit. The odds are good that Crested Butte holds some kind of record for per-capita bike ownership, with the fat-tire machine de rigueur as the basic item of transportation. There are bicycle events of all descriptions, from professional stage races that attract the likes of Alexi Grewal, to Fat Tire Bike Week, the Olympics of the mountain bike world where Rich Cast rode over a picnic table (both ways). People cruise through town above the smooth hum of two and one-quarter inch knobbies, mud-spattered from head to toe, and nobody notices.

(But even here, somebody could ask, “Hey, are you the guy with the bike?” and make perfect sense. Ain’t language wonderful?)

The sequence of events during my nine-day stay was simple enough: I hung around, met a delightful actress-landscaper named Glo, moved in with her, rode around, wrote an article, climbed a mountain, and left. Not much of a story. But the homelike texture of the place has lingered like the warm memory of childhood Christmas, and therein lies the beauty.

Crested Butte women own mountain bikes, clamber up steep slopes, hunt wild mushrooms, and radiate the healthy glow of fresh air and exercise. Their grace is animal grace, not fashion grace. They have long hair, they don’t shave their legs, and they live in a community so close that their periods are synchronized.

This has interesting implications. I sensed it immediately: I felt like a welcome visitor in a large family instead of a stranger in a small town. This is a well-recognized truth about the place, leading some to observe that “affairs here feel like incest.”

(And people can always tell when you have aunts in your pants.)

Of course, I was a mere ephemeral diversion in a maelstrom of existing relationships, all intertwining like ancient vines. I’m used to cities where circles of friends are but distantly connected, where only rarely can the system of human bondings be called a network. A couple in Columbus is an island (Isle of Ewe?); a couple here is one of many possible cross- connections within a closed system.

As a result of all this, Crested Butte is a unique social universe. “Everybody here has seen everybody else naked,” observed a lady over a flawless spanakopita one night, whereupon a fellow across the table cried, “Wait a minute, I haven’t seen you naked yet” to which she replied in surprise, “Nor I you!”

Yet it hasn’t the flavor of wanton promiscuity at all, for there can be no anonymity in a family this size.

I kept feeling this during my ten-day stay — in the hugs on the street, in the obvious closeness of old friends. It is especially visible in the bars — the Grubstake, the Wooden Nickel, Donita’s. In most cities, a bar is a stressful place for someone like me. Here, a bar is a gathering of friends — people hugging, talking, and relaxed; a cozy group sharing a bit of warmth and only incidentally on the make.

Perhaps that has something to do with snow, a phenomenon deeply respected in small Colorado towns. I stood on the street one afternoon, chatting with a small group of people while kicking around a meatball-size leather sack. This is a common sight here — clusters of friends diverted from casual errands by each others’ presence, engaged in meandering conversation punctuated by the cooperative pattering sounds of hacky-sack.

So there we were. Time mattered not.

“What are you doing to play today?” someone asked someone, squinting in the high mountain sun.

“Oh, I thought I’d take the lower loop out to O Be Joyful — I just got my cantilevers fixed.”

“Feel like climbing Avery tomorrow?”

“Hey… nice idea…” But in the lull of speculation there came a single clink/crack/thud, the unmistakable sound of somebody splitting wood. A hint of winter was in the air.

The faces of my friends changed from easy relaxation to resignation and quiet dread. That sound…

“I was up on Taylor the other day and some of the aspens are starting to turn…”

“Yeah. I haven’t even started to get my wood in. I burned almost nine cords last year.”

I listened, knowing I’d be pedaling south, trying to imagine the eaves-high snow and relentless cold of a mountain winter. Some flee to warmer climes, to other playgrounds of the spirited like southern Arizona, the Bahamas, Key West. But most stay and grow closer still, a people as united in their defense against the elements as they are in the delight of flying through them with waxed skis a-flashing.

Crested Butte is the land of the urban drop-out. It feels like a college town without the college, a place of un-self-conscious consciousness and casual intellect. Most waitresses have degrees — and people tip well, around twenty to twenty-five percent (“We’ve all been there,” someone explained, “and most of us still are.”)

It’s an odd demographic twist, this place. It ranks high as far as per-capita education is concerned — right up there with California’s Marin County — but it has a median income of less than $20,000. This is an alternative to suburbia, a playground for professionals who have rejected the prevailing work ethic. The size of the paycheck isn’t important as long as you can afford rent, food, and the essential equipment of biking, climbing, and skiing.

(What else do we work for, anyway? Numbers?)

At a backyard cookout one night, I took a break from wrestling on the lawn with the dazzlingly bright seven-year-olds Elsie and Zooey. The adult conversation around the fire had different content, but the same sense of childlike wonder and life. Talk was of play, beauty, fun, people, mountains, and who was doing what for the winter. One of the guests announced that his vacation had started that day.

Thinking conventionally, I asked, “So where are you going?”

He looked at me, startled. “Going? Why would I want to go anywhere?”

Inevitably, there are problems. Magical little places tend to attract people, too many people — and not always the right kind. While things haven’t gotten bad enough to make residents start locking their doors, some folks are getting upset.

(Let Glo tell it: “I locked my door once, about six years ago. I was getting it on in the bedroom when a friend showed up. He was so shocked to find the door locked that he reached through the window and let himself in.”)

No, the problem isn’t theft, it’s development. Crested Butte has one advantage over other attractive places: community planners were wise enough to put the ski resort a couple miles up the mountain from town. That, not the Butte itself, is where you go for a $4.95 steamed artichoke or the stirring sight of round-the-clock condominium construction. But distant or not, the impact is felt. Transient construction workers, vacationing skiers, tourists, wandering high-tech nomads…

Yup, it’s the classic problem. The town doesn’t want to grow but it has to; it depends on tourist income but must fight growth to retain the character that keeps them coming back for more.

I started to notice a phenomenon in this little town of 1,200 people. There is something special about places where people want to live — places isolated, fun-oriented, and ruggedly beautiful — something that leads to the development of a society unlike any other. Part of it is that sense of “home” that extends beyond the confines of individuals’ property. People care about their town, not just their yard, and they don’t want to be chased out by crime, traffic, and overcrowding.

Visitors sense this, as I did; they sense the comfort of the old couch and they don’t want to leave. They come and marvel at the magic ambience of a real community, then they stay and dilute it. Everyone wants to be the last one in; hell, even as a confirmed transient, I started looking at other newcomers with a trace of resentment after only three days in town.

Of course, my Crested Butte experience was hardly typical — I moved within twenty-four hours into the very heart of the place. With one smiling hello, I penetrated the buffer zone that separates the community from the tourists; with a single giggling lap ride, I endeared myself to one of the town’s premier social butterflies.

Glo’s work is “landscraping” but her passion is the theater. Everybody knows her, and this Crested Beauty was such a focus of energy that time alone with her was a rare treat. People dropping in, the phone ringing, cheery waves to passers-by — to touch Glo was to touch the very spirit of the town.

I was fortunate enough to arrive during the staging of Shadow Box, a production of Crested Butte Mountain Theatre. I confess I took it lightly at first, having become jaded by amateur theatrics over the years.

But then I went to see it.

The characters were so convincing, so thoroughly immersed in their parts, that I forgot the real people I knew — even Glo — and saw instead the emotionally exposed participants in this drama of death. The play raised thoughts of mortality in the eloquently developed relationships of three terminal cancer patients and their families.

Each brought into focus that evolution from suspecting your own mortality to becoming certain of it. There was a writer who tackled the end philosophically, but remained in terror of the abyss. There was an old woman who bargained with the reaper, refusing to die until her long-dead daughter came to visit. And there was a man who realized in despair that nothing was permanent after all, and now struggled with an unaccepting wife and the task of telling his son.

The players wept, uttered passionate monologue, and lived their scenes with raw emotion. I looked into the eyes of people I was coming to know and saw instead the characters in the play. It was theater at its finest.

Death.

I thought of the accident with the old rancher, the red guitar in Key Largo, a gunshot near South Fork, and the drunk from Antonito. The Indianapolis expressway, Slumgullion Pass and hypoxia in the mine, dehydration in west Texas. Impromptu rock-climbing near Lake City, alone and without equipment — an unstable slope too dangerous for my meager skills.

Yeah, death. It’s out there, waiting. It won’t go away. Sometimes it leaps at you from a passing truck; sometimes it grows inside and pulls you down, slowly, cell by mutated cell.

Death. We have to accept it, but we don’t want to, not yet, not yet, not ever yet. “You are approaching an absolute unknown absolutely alone,” said the writer in Shadow Box, and as I pedaled reluctantly away from the cozy little town of Crested Butte I had a new recognition of life’s fragility.

It was hard to leave. I lingered over a delicious “Baggins” breakfast at the Forest Queen and regretted my departure, wondering what the big hurry was. Fat Tire Bike Week was just beginning, and the energy of the town was even higher than usual.

But wanderlust is not necessarily rational.

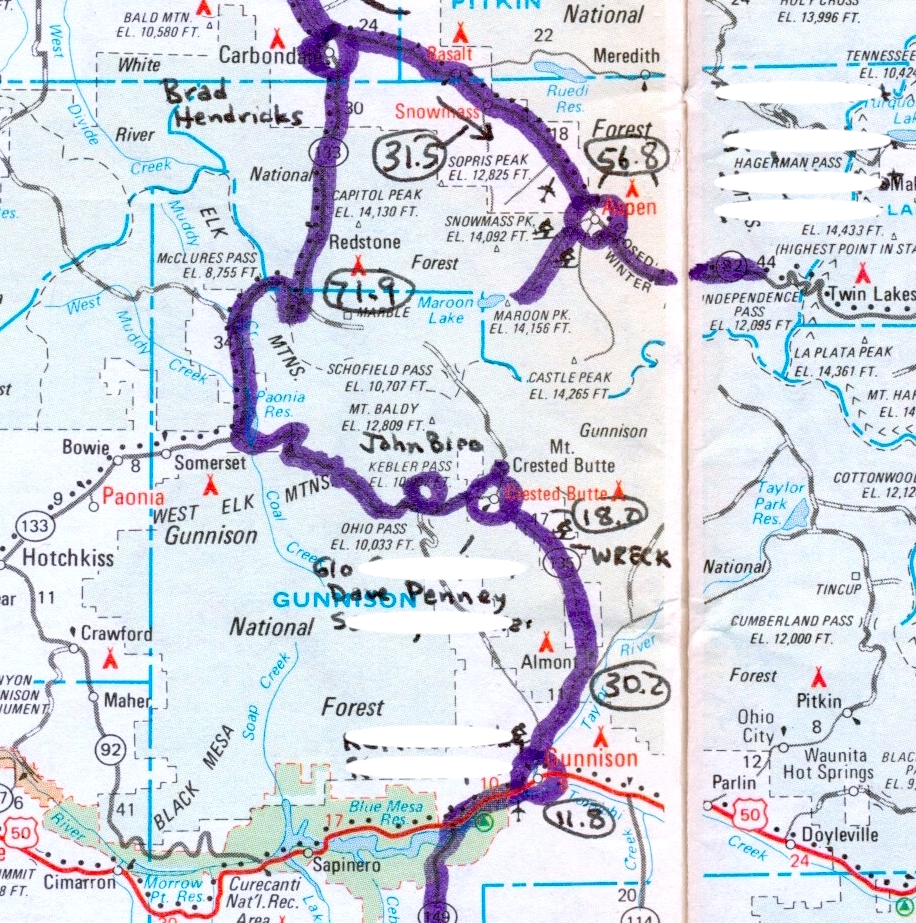

Kebler Pass was cake — twelve miles of easy grade, packed gravel washboarded on curves where the side-loading of tires had stressed the surface. Pine forests, occasional cars, and a succession of exhausted mountain bikers on the final downhill run of their mad race over Gunsight Pass (something only the most hard-core even attempt in Jeep).

It was a twelve-mile ride from one paradise to the next, from the Butte to John Biro’s ruggedly beautiful handmade home near Lake Irwin, above 10,000 feet. I went Zen fishing with a Navajo friend, paddling the canoe

under her vaguely spiritual direction: “This spot feels right… no, over here just a bit…” then she would close her eyes and drop the lure.

No luck.

But we settled into John’s cabin for the night, remote and idyllic, a place hand-hewn with passion. Arco solar cells power a twelve-volt electrical system. A composting toilet “flushes” with sawdust. The centerpiece of his cozy kitchen is a massive Elmira wood stove, and the room is scattered with cast-iron cookware and home-canned foods like the very image of frontier independence. Thick insulated doors have antler handles, the view is of a deep valley sunset, and the nearest pavement is ten miles away.

I relaxed with a full belly, thinking of the road ahead and the endless miles… and suddenly noticed a change of attitude. This whole affair had begun as a trip, a temporary adventure, a hiatus from my “normal” life. But it had now become my normal life — a full-time profession with no clear end. Someday, in a place like this, there would be a week’s layover that would become a month, and then a year, and then more…

I would only recognize my journey’s end in retrospect, if at all.

Around me in the cabin were sounds: Earl Klugh on the stereo, a pan sizzling dishwater on the woodstove, grunts from the black bear of a dog. The twelve-volt lamp glowed yellow on the paper of my journal. The rich wood around me — heavy, thick, warm — disappeared into murky corners harboring bone-crunching cats, one of which had been the butt of our respectful derision a moment earlier.

We were sitting in stuffed laziness around the table, you see, talking about whatever, sipping wine. The cat sat on an empty chair and stared fixedly at the chicken remains, at last deciding to go for it. She put her forepaws on the table, then froze under John’s warning: “Hey! You know better than that!”

She looked guiltily up at him and then, closing her eyes so nobody could see her, leaned forward to smoothly take the meat.

The next day.

I sat in the sun in a vast aspen forest that stretched for miles, yellowing here and there below the incomprehensible mass of Mt. Baldy. Trunks flashed white in the sun, the interplay of gleaming bark and deep shadow wondrous to behold. The only sound was the roar of white water beside me; the smell a mix of late summer woods and my own healthy sweat.

This was an on-the-road break, on the down side of Kebler Pass. The beauty was too intense to pass without contemplation, and as the sun flickered green-gold through the tangle of leaves I sat writing on the new computer, thinking, and savoring the sweet loneliness of a time so perfect that I ached to share it.

I had a flat tire a few miles before, and wasn’t even annoyed by it; I met a wise old man in a camper and joined him and his dogs for a lunch of fresh trout.

But the rest of the descent was a long, difficult project, the 3,300-foot drop to Paonia Reservoir a brutal test of brakes and nerves. Riding the drum brake to prevent rim heating, I picked my way around potholes and rocks, bouncing for two hours over a washboarded gravelly road so rough that I couldn’t even listen to my tapes for all the vibration. I choked and blinked away eyefuls of dust with each passing car, my back aching.

By mid-afternoon, I reached the reservoir, a mess of construction and traffic. And then gradually up, the beginning of McClure Pass. At 5:30 in the afternoon I was starting a pass. Not wise. It had its moments, of course: the pleasure of real pavement, an old Led Zeppelin tape, the startling of a doe and fawn. But mostly it was work, my appreciation of the beauty gradually giving way to bitching at my own grim little world of sweat and pain, hard work and exhaustion.

I was fading — along with the daylight and my water supply. There were yet many miles to the top, and over twenty miles after that down to Carbondale. I stopped to rest for a bit, then threw the chain when starting again.

GOD DAMN IT!!! Cursing all derailleurs and especially this one, I greased my fingers and tried again, crunching the chain. The words flew, loud and frustrated. I fixed it again, and in the middle of sliding slippery hands together in a black/brown mess of waterless hand cleaner I realized what was happening.

I looked closer. Trouble. The freewheel was stuck, the right dropout scarred silver from the grinding cog. The tire was warm from rubbing on the frame, and the drum brake housing spun freely. I stared numbly at it. I had just spent two hours struggling up a mountain with my rear wheel jammed so tightly that I could hardly turn it by hand.

I sat in the dirt, defeated and angry. The bike had been reliable for seven thousand miles, and now, with a broken hub, I was stuck alone on a cold mountainside in the dark. I hated it. All the exhaustion and frustration spewed forth, and I even threw a wrench. The moment was as low as had the sunny streamside reverie been high.

Not really caring about damage, I took the whole mess apart and whacked the bearings back into line. Riding the drum brake all day on Kebler had probably done it, so I disconnected that, threw everything back together and went on. Up. Up, damn it, up. There was no joy anymore; I just wanted to get there — and with that kind of attitude, a bicycle is a poor vehicle indeed. Up.

Finally. Pitch dark, cold, the 8,755-foot pass. Here and there, far away, random lights. No water. This really sucks — Roberts, you’re an idiot. Still twenty miles to ride.

OK… all lights on. I had no idea what lay ahead, only that I was about to lose 2,500 feet of elevation with a floating wheel bearing, disabled drum brake, and glazed, useless sidepulls. With no real alternative, I pushed off.

Dark hulks of mountains against dark sky. Flashers ablaze, bugs bright in my headlight, curves materializing without warning. It started easy, but in growing panic I watched the grade steepen, my speed climb into the forties, the sense of control diminish. My only visual cues of the road ahead were the blurred white lines a few feet in front of me and a tiny pair of headlights stabbing the night a few switchbacks below.

I leaned hard into a hairpin turn, squeezing the one brake lever and sensing only slight deceleration. This was a blatant flirtation with death. An animal darted across the road and my startled steering reflex set up a sickening oscillation. Still the speed climbed, almost to fifty, blowing the helmet back on my head and roaring in my ears.

I was out of control.

An orange reflective dot appeared far ahead — a sign. I squinted into the screaming blackness to read it, eyes watering, heart racing, legs shaking, thoughts turning like a recurring nightmare to the broken wheel bearing and useless brakes. Would there be a guardrail to mangle me first, or would the road just disappear with a brief gravel crunch, leaving me wondering during that endless cry when the invisible rock would rise from the dark to shatter me?

My teeth hurt from clenching; my temples were frozen with wind-whipped tears. I began to get images of my life, distant vignettes of deep sadness. I had left so much untouched, so much unpublished. McClure Pass. I had a neighbor named McClure back in Dublin… ah, Elisse, sorry, I should have written… would they reconstruct my bike like an airplane to determine the cause of the crash? Oh no, I forgot to mail that pretty piece of feldspar to Amy…

The sign flew past me in the lonely mountain night:

I might have closed my eyes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.