Computing Back Across America

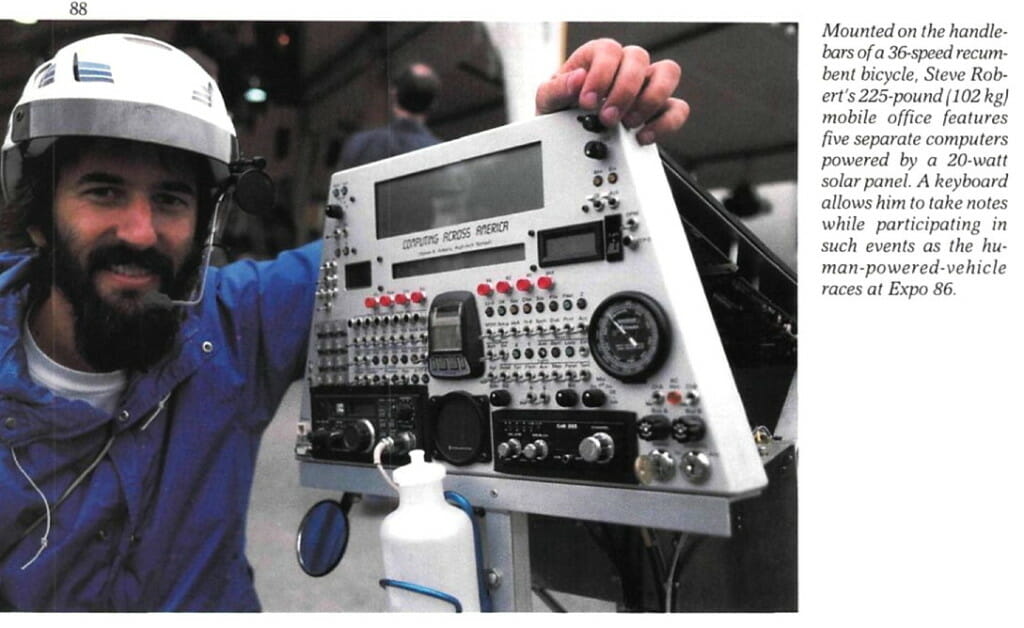

This little piece marked the beginning of my move from CompuServe to GEnie, and was posted to my new “Computing Across America” area there. This was the start of what became known as the Miles with Maggie phase of my adventures. The photo above was from May 1986, and we had only been dating for a couple of months. We found a recumbent bicycle for Maggie, and did an overnighter from Dublin to Marion (her old hometown) to sample the crazy idea of taking off together on a grand adventure around the US. I was just building the Winnebiko II console, and integrating it into the original Winnebiko that had already carried me 10,000 miles. This was a pivotal moment: network home, technomadic substrate, and romantic partnership were all changing at about the same time… and I quit my engineering job at Discovery Systems to focus on the new bike, ending the brief flirtation with security.

Steven K. Roberts

Nomadic Research Labs

Columbus, Ohio

May 28, 1986

Did you ever want to break the chains that bind you to your desk and just take off, wandering the planet while making a living doing whatever it is you love the most? Seems reasonable enough… and three years ago I did just that. Since then, I have been living in an electronic cottage on human-powered wheels, and through these stories I’m going to share my adventures with you.

We’ll be covering the burning issues of the day: Adventure, love, danger, weird people, radical extremes of network living, full-time travel, high-speed flights down mountain roads mottled with Aspen-shade, mycological tone poems, unexpected ice caves, bizarre contraptions, ham radio, satellites, a 200-pound bicycle worth $100 a pound, real-life wizards, regional humor, outlandish microprocessor applications, ridiculous comments, random controversy, moments of pure anguish, and so much fun that something about it must be illegal. For starters.

I am an agent of future shock—a high-tech nomad, a pedal-pushing freelance writer head over heels in love with that sweet piece of asphalt known as The Road. My home, if I can be said to have one, is Dataspace; my vehicle, the Wondrous Winnebiko. My computer is a Hewlett-Packard Portable PLUS. Yes, I work for a living: my business is to have a wildly exciting life and then tell people about it.

(It’s a lousy job, but someone’s gotta do it.)

This is the first of a series—a collection of tales too strange to predict and too diverse to summarize—an ongoing travelogue of a romantic high-tech bicycle odyssey. As I move into the second 10,000 miles of this open-ended journey, I have switched networks and suddenly find myself in a whole new community. (Why should I restrict my nomadics to physical space? Howdy, neighbor.)

So lemme settle in here and take an angle-bracketed <sip> of compu-booze, then tell you a story…

The First 10,000 Miles

In September of 1983, I sold my 3-bedroom ranch home in Midwestern Suburbia and moved to an 8-foot-long computerized recumbent bicycle bedecked with solar panels and enough gizmology to start a science museum. I quickly discovered that this was not to be just another bike tour. Using CompuServe as my link with the universe, I maintained a full-time freelance writing business while pedaling a 9,760-mile journey around the United States.

I lived for the moment — and I had many. During the 18-month adventure, I fell in love both on and off-line, encountered a band of convicts in the Maryland woods, sailed through the Gulf of Mexico, tempted fate more than once, and learned more than I could have ever imagined. I overheated in West Texas, froze my ass in Utah, discovered Key West hedonism, and explored the California mystique. In Santa Fe, I saw firsthand the symbiosis between hawker and gawker; in Crested Butte, I witnessed a community so close that everybody’s biological cycles are synchronized. I ate crawfish, oysters, and GORP — I prowled the country seeking the exotic, sexy, and bizarre. The stories flowed like hot breath, and soon the media turned its unblinking eye on me as a high-tech curiosity, a peripatetic eccentric, a symbol of freedom. “Charles Kurault on a bicycle,” gushed one local TV station as I pedaled into a perfect cliche of sunset.

And I came to realize, looking back into the eyes of all those people looking wistfully at me, that the greatest risk of all is taking no risk. I noticed (once I stopped trying to score new states) that if you think too much about where you’re going you lose respect for where you are. And I dedicated myself to resolving the classic trade-off of freedom versus security — a task I think I’ve finally accomplished.

Ah, and the people. When you look like something out of a nonviolent version of The Road Warrior, you tend to open a lot of doors. Even if most of them turn out to be closets, the numbers are there: I spent months probing the asymptotes of America and finding brilliance in the oddest of places. I found communities ranging from the vaporous to the ancient, and was tempted time and again by their seductive tug. And I glimpsed the potential of life online, a life outside the strictures of physics, beyond the limits imposed by image and prejudice. In the electronic pub, brain meets brain and conversation ranges from the bawdy to the sublime.

Life aboard the Winnebiko is a life of extremes. I am at once a being of cloud and soil, satellite and bicycle — living two simultaneous lives. One is visceral, sweaty, attuned to every hill and headwind — the other is ethereal, intellectual, an electronic interlocking of imagination and communication. Something about the contrast casts both aspects into sharp relief, and I suppose I’ve become something of an online proselytizer.

9,760 miles. The journey wound down a year ago in the frenzy of approaching book deadline — along with the exhaustion of some 2.5 million pedal cranks and over 200 different beds. (Time for the commercial: the book is called Computing Across America: The Bicycle Odyssey of a High-tech Nomad.)

Anyway, the bicycle sat dormant for a few months in a Silicon Valley attic, then found its way back to the land of its origins for six months on the operating table. And that brings us (far too quickly) to today.

The Next 10,000 Miles—A Sort of Prospectus

It’s happening again; I can feel it. Every daydream involves the Road; any new purchase has to be something “bikeable.” The journey is obsession, addiction, religion, and lifestyle of choice — by August I’ll be rolling.

Ahh.

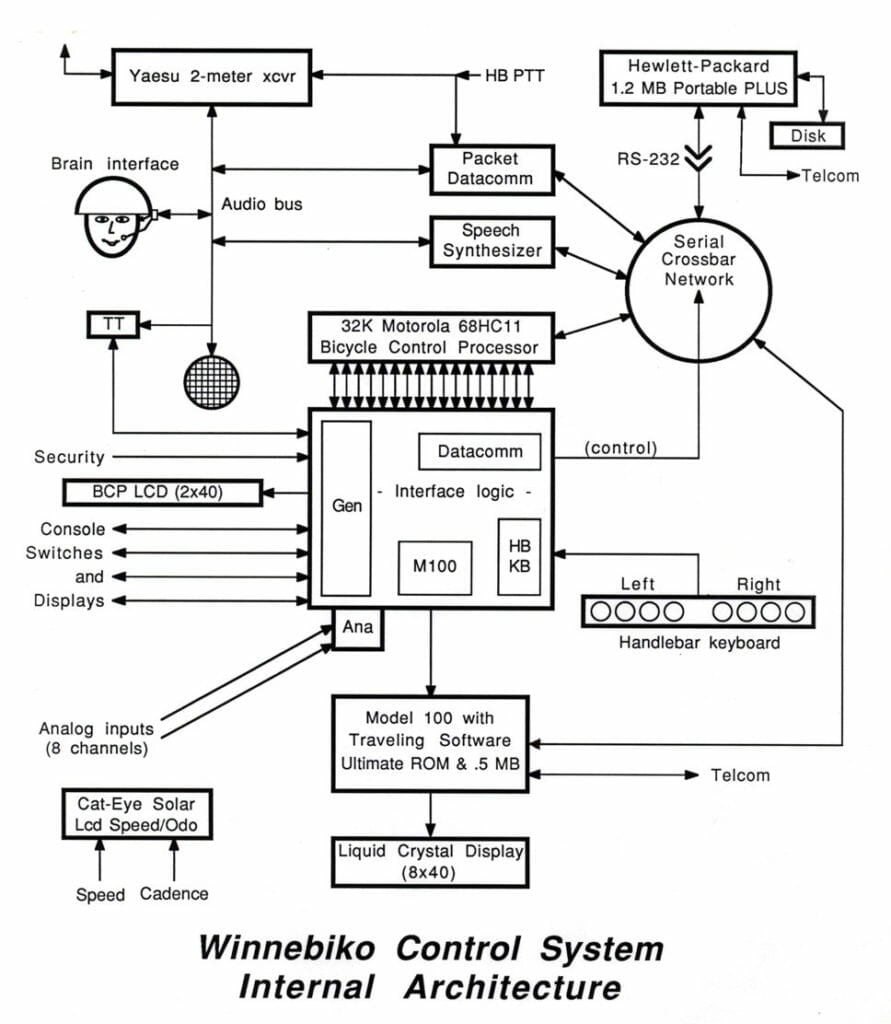

But there are differences a-plenty. The Winnebiko is again the substrate, but it’s now layered with more exotic systems than ever. Not including dedicated controllers and “smart logic,” there are four on-board computers — along with a satellite data link, ham radio station, and navigation equipment.

The biggest problem on the first trip involved time management, something that affects nomads as much as it does executives. I spent roughly half a business year pedaling — 1,000 hours sitting alone on the bike. I would cruise all day across American vastness, composing tales in my head and itching to get my hands on the H-P Portable riding behind me. (“Ah, such a chapter shall this be!”) But by evening I would be tired and hungry and surrounded by people clamoring for stories… and the day’s ideas would drift away like the smells of camp cooking, gone without so much as a memory of the insights that spawned them. Wasted.

And so the bike has become a rolling word processor. There are two liquid crystal displays on the console in front of me, and a keyboard built into the under-seat handlebars (eight buttons for text along with various other controls). A dedicated 68HC11 microprocessor performs key code conversion while attending to bicycle management tasks, decoding finger combinations based upon an arcane letter-frequency-based coding scheme. Whenever a valid character comes along, the 68HC11 passes it off to a handful of CMOS logic that is interfaced to the guts of a Model 100 — making everything described so far look exactly like the original Radio Shack keyboard. The net effect is a full screen editor that I can control while pedaling.

But it doesn’t stop there. An RS-232 line allows text in the tiny 32K buffer to be transferred to the 896K Hewlett-Packard system — and from there to disk via the 3.5-inch floppy drive. Two modems cover all combinations of pay phones and modular jacks, and a fourth processor (CMOS Z80) handles AX.25 protocol control for packet data communications through the 2-meter ham transceiver… which will soon include an orbiting electronic mailbox known as Pacsat. Of course, all this takes power, and the original 5-watt solar panel has been replaced with a pair of 10-watt Solarex units — along with 8 amp-hours of Nickel-Cadmium battery to hold it all. Other electrical loads on the Winnebiko II include twin air horns, lights, flashers, Etak electronic compass, paging-type security system with distributed sensors, CB radio, stereo system, cassette deck for dictation and music, digital shortwave receiver, and the usual speed-distance-time-cadence instrumentation.

“Are yew with NASA?” asked the Ohio farmer, slowly chawin’ tobacco while peering at the strange apparition gleaming beside the small-town pay phone.

“Sure,” I answered, looking up from my online session on the burning pavement. “This here’s one o’ them Loony Excursion Modules.”

And Now…

It will be August before everything (including the business structure, subject of my next article) is working well enough for me to abandon this tacky apartment complex to experience, once again, the pure exuberance of full-time travel. Once on the road, I’ll publish weekly updates on GEnie; in the meantime, I’ll post an occasional message to let you know how the preparations are coming. I welcome your responses, suggestions, and invitations for the hospitality database (another of the H-P’s jobs) — I can be reached via GEmail as WORDY.

And maybe somewhere, out there, we’ll meet. I’ll spend my life prowling neighborhoods electronic and physical, pausing for months at a time to explore and touch the magic. I guess that’s the point of all this… I finally figured how to get paid for being a generalist. And I couldn’t possibly do it without computers and networks.

Ain’t technology wonderful?

You must be logged in to post a comment.