The Consoles of my Life

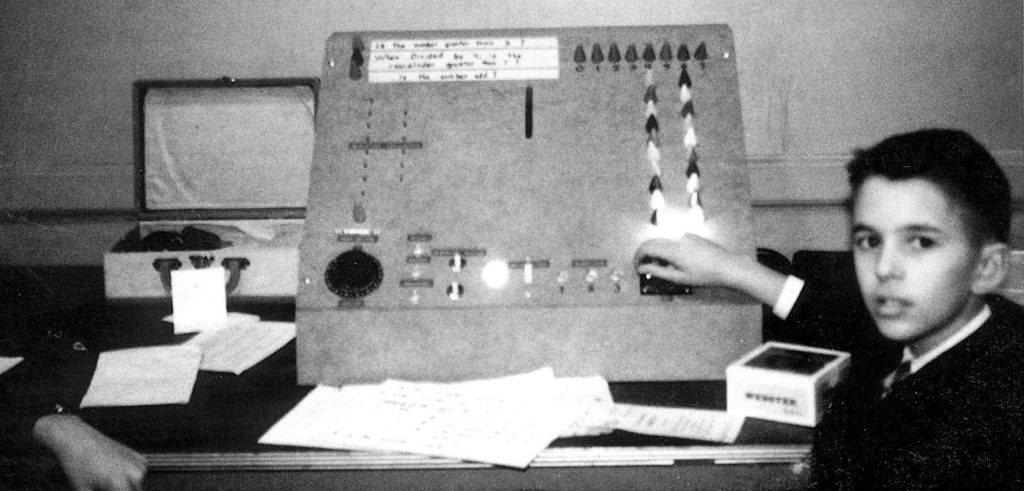

Over the years, there has been one stylistic constant in my pursuit of übergeekery: equipment consoles. It started one 1964 afternoon in Louisville, when this skinny 12-year-old electronics-obsessed geeklet got a peek at how the big boys do it.

Via a ham radio friend, I had wangled an invitation to visit the avionics maintenance shop at nearby Bowman Field. Aircraft radios and navigation instruments were repaired and calibrated here, and I got to hang around and ask questions until the experts got tired of an eager kid wanting to know their secrets.

That was fun, but what really grabbed me (and what I still remember more than a half-century later) was the tall black-crackle equipment racks filled with test equipment. Nixie readouts flickered orange numbers, d’Arsonval meter movements showed DC voltages or danced to audio, magic-eye indicators showed receiver tuning, round cathode-ray tubes displayed green modulation envelopes and 60-cycle power-supply hum. Red and black test leads dangled like umbilici, probes tapping signals deep in the inscrutable depths of circuitry on the bench. I was enthralled.

Days later, I got in trouble in history class for drawing the rackmount equipment console of my future laboratory instead of paying attention to Hadrian’s Wall… or maybe the Magna Carta. Whatever.

And so it began.

The Basement Lab of my Youth

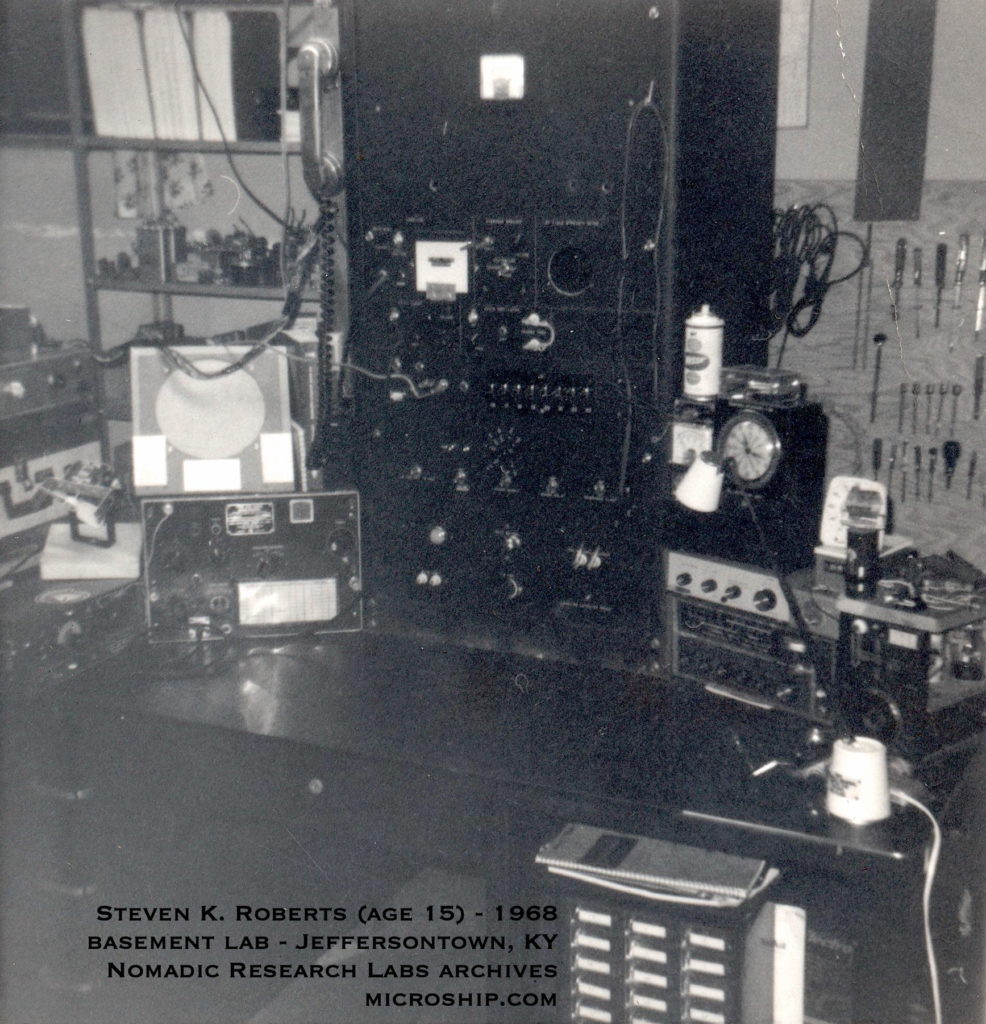

It didn’t take long before I scored my first rack, which soon dominated my paleogeek lair in the basement of our Kentucky home:

This rare 120mm photo shows gizmological treasures I remember with deep fondness: military-surplus ham radios including an ARC-5, shortwave and CB radios, homebrew unbuffered 80-meter 50C5 crystal oscillator, stealth phone with dial hidden behind solenoid-locked access panel to discourage parental snooping (ringer equivalency was a big deal then), Variac and DC power supplies, an old hotel clock with switch output, homebrew Morse Code translator, stereo amp, and parts inventory.

I was a lonely nerd, and this was my happy place… down in the musty basement, around the corner from my dad’s well-equipped workshop with its huge tool board and wall of fasteners. Audio feeds from all over the house snaked to a selector switch via the ductwork, and Great Projects were always brewing. I had a novice-class ham license (WN4KSW, which still rolls smoothly off my fingers in CW) and I ran weekly Civil Air Patrol cadet nets on 26.620, just below 11 meters. I looped a few turns of copper wire totaling 8 ohms around the room, stapled to joists overhead… then drove it with an audio amplifier so that a loopstick antenna attached to a high-impedance military headset would serve as an air-coupled secondary… letting me listen to any source via passive wireless headphones as I worked.

This was my workspace through high school, and then I had a brief flirtation with two quarters of engineering school, hitchhiked around the US for a while, worked as a deckhand on barges, got a job installing Autovon central office telephone equipment on Army bases, and stumbled into the Air Force in the summer of ’71. (Much more about all that is in my Prehistory of a Technomad story.)

Air Force Tech School Dormitory

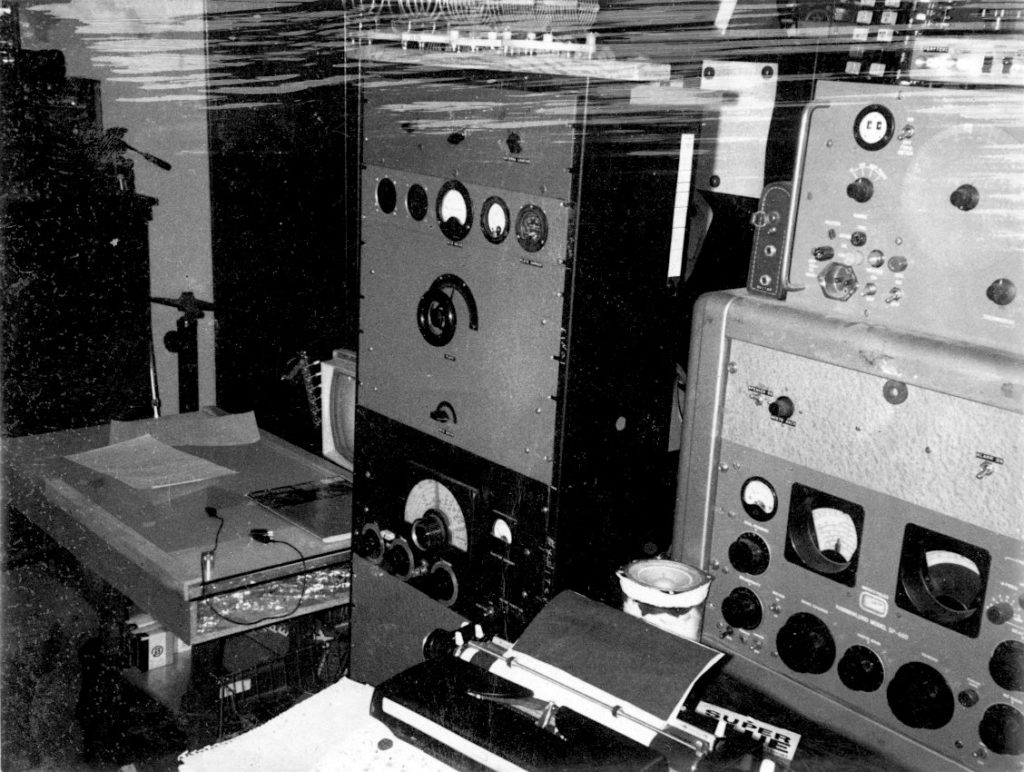

In retrospect, I can see why I was a bit of a disciplinary problem. After a most unpleasant Basic Training, I landed at Keesler Air Force Base for tech school during the Vietnam War era… learning avionics, terrain-following radar, and navigation systems. The studying was not difficult, and my passions were elsewhere: the pharmacological pursuits of the time, zipping around on a Honda CB450, snooping where I shouldn’t be, hopping freights, and tinkering with electronics in my dorm room (much to the dismay of Ken, my tidy roommate).

That glorious Tektronix 531 oscilloscope came from a surplus outlet in New Orleans, but my real love was the Hammarlund SP-600 shortwave receiver. This became a defining component in my life, connecting me to the world of international broadcasters… listening to exotic political news from all perspectives even while plodding through Air Force tech school.

The unit to the right of that was a Beckman “Universal EPUT and Timer,” basically a frequency counter with annoying columns of numbers that would dance up and down. Atop that was a tool for research on telecom signaling protocols…

(As I wrote a decade later in Computing Across America: “I had traveled much in my mind back then: cloistered in a stark third-floor room, catching glimpses of infinity through tiny windowpanes, hopping around the globe via shortwave radio, and disappearing into the works of Huxley, Stockhausen, and Signetics.”)

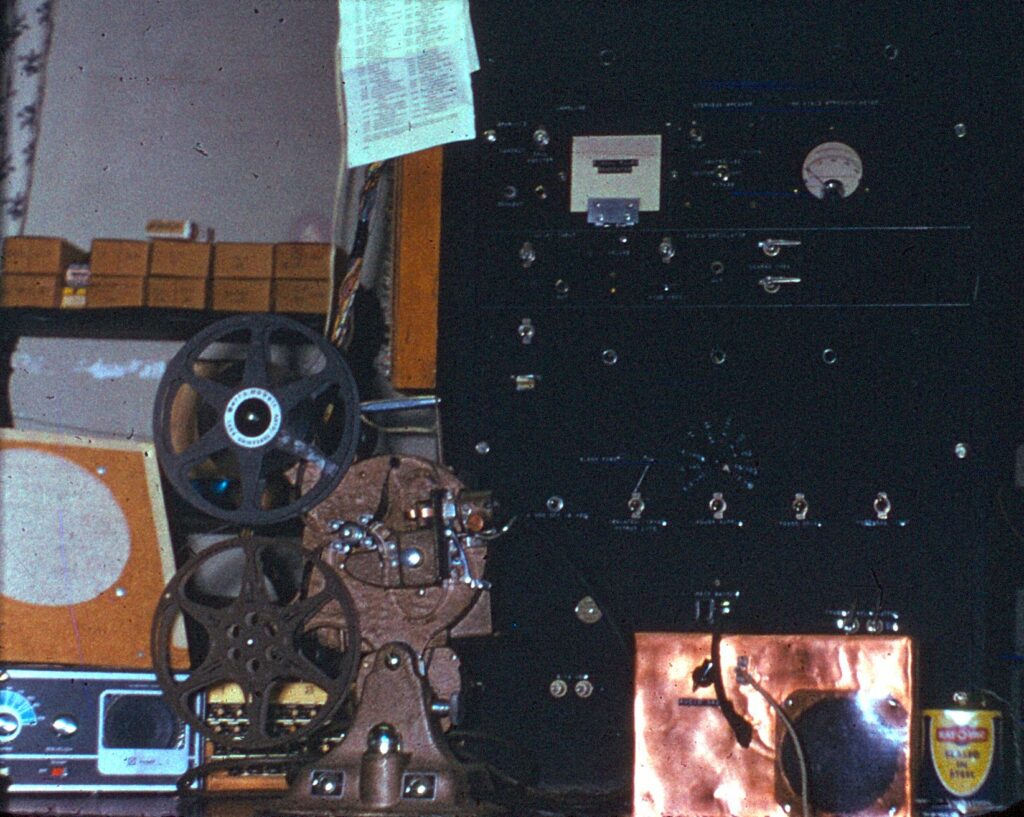

The Dorm Lab of Mountain Home

By now it was 1972 and I was 19… precocious and annoying to my military superiors. My day job was avionics maintenance on the squadron of F-111 jets, but otherwise my time was my own. I threw everything I had into projects, ham radio, zipping around Idaho in a ’59 bugeye Sprite, cycling mountain roads on a sleek Olmo, reading, buying tools, design circuitry for my arbitrary waveform generator, and trying to get out of the Air Force (we really weren’t right for each other). They had not encountered this kind of a disciplinary problem before, so my life was a slowly brewing storm.

The room layout quickly became untenable for two, and somehow my roommate managed to move and I was able to stay there alone. A bed would be a waste of precious square footage, so I built a cave behind the 4×8-foot workbench and crawled in to sleep. To the left was a 6-foot rack filled with ham radio gear, along with a homebrew light table for printed-circuit layout.

The transmitter was a beast — a pair of 100TH triodes in push-pull, driven by an AM exciter and tuned by a bunch of open-air coils and a huge capacitor with steering-wheel knob. My stealth trapped dipole on the 5-story building was not optimum, and the splatter might have interacted with a stereo or two when cranked to its full 600 watts…

The Sony reel-to-reel helped build soundtracks for my excursions into the infinite, and that barely visible TV to the left of the transmitter was wired to display music-driven Lissajous figures with the guns biased by a color-organ. Light shows with CRT and He-Ne laser diffraction, decent stereo with homebrew glass speakers, shortwave pulling in signals from all over the world, my synthesizer design, the wondrous new HP-35 scientific calculator, tinkering with the Hagstrom guitar, late night hikes in the desert, the wall of books… my USAF responsibilities were fading into the background, and I think I might have had attitude problems.

This all came to a head, inevitably. My cat disappeared, and I got wind of inspection visits taking place when I was at work. I responded by building an intervalometer surveillance system with an old 8mm movie camera taking one photo per second, along with a massive Wollensak tape deck in the closet that would come on whenever the door was opened, recording as the camera ticked away and “cooling fans” masked the noise.

I captured three visits by the inspectors, which included snooping in my file cabinet and some other “no-no” activities, ironically simplifying my exit from the USAF by adding weight to my claim that I was being harassed (not that I ever did anything to encourage that!).

The machine in the photos that caused by far the most trouble was the typewriter. But that, as they say, is another story. (A few more photos of the room are over here.)

All of this was short-lived… I only spent about a year at my Idaho duty station. While waiting for the honorable discharge to come through, I was moved to the Precision Measurement Lab (PMEL), where I actually started to have so much fun that I might have willingly stayed on for the entire tour had we not already burned a few bridges. I rented a truck, packed the Sprite and console equipment inside, and drove home to Kentucky.

Life with a 1974 Homebrew Computer

After the military incursion, I found a job as a field engineer for Singer Business Machines… taking care of the System 10 used for barge tracking, point of sale terminals at Sears, hospital management, and other fragile installations in the early data processing marketplace. They sent me to tech school in San Leandro, putting me up in the Edgewater Hyatt, and in addition to unsuccessfully questing after the mythical California Girls, I discovered the local electronic surplus market.

I set up a lab in my poolside hotel room and started teaching myself logic design, memory architectures, interfacing… driving housekeeping crazy with blinky tangles of geeky goodness spread across the makeshift workbench, beige carpet littered with wire strippings and solder splashes, chip databooks piled in the bathroom. And as the tools made more and more sense, I grew obsessed with the idea of building my own computer.

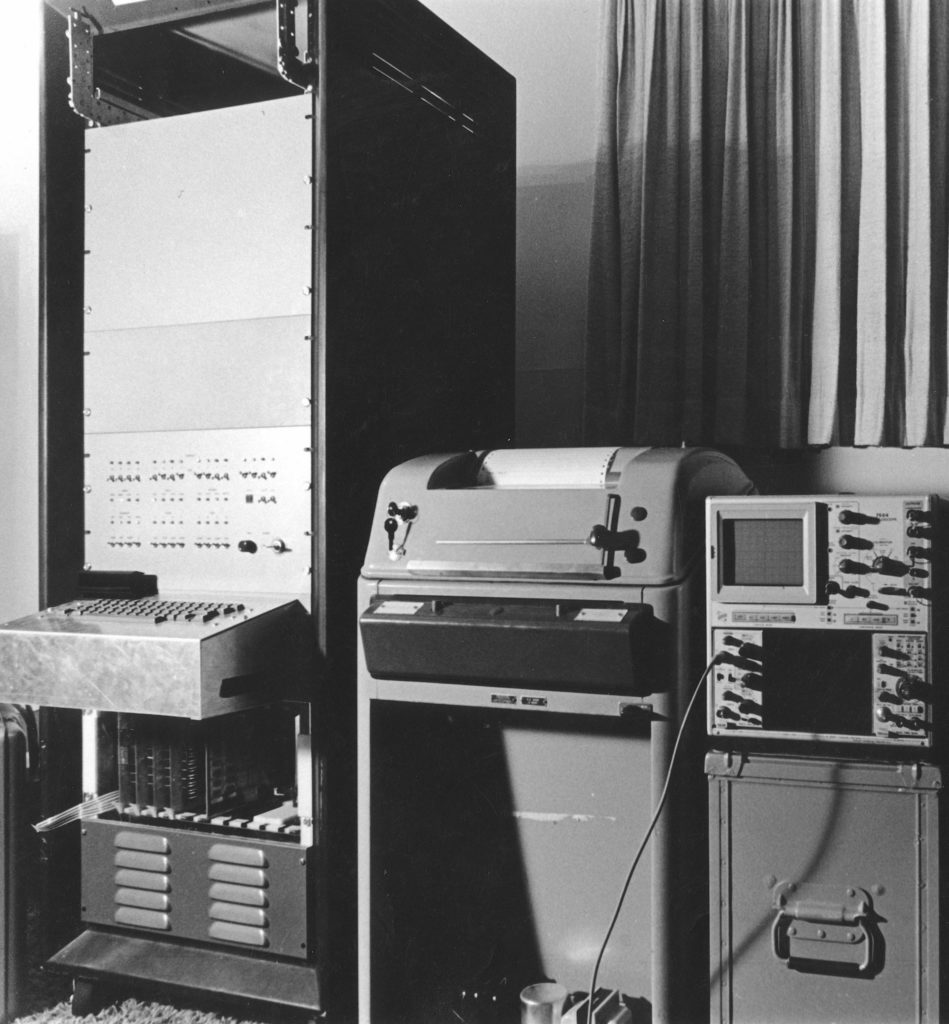

I got home and threw myself into the project. It was early 1974 and personal computers did not yet exist… so this was virgin territory. I set aside the gritty process of basing it on my own random logic (with 74181 Arithmetic Logic Units) and took advantage of the first 8-bit micro (Intel 8008)… designing a 60-chip CPU board supported by four I/O boards in a card cage. On Halloween, the wire-wrapped machine first flickered to life (now in the Computer History Museum)… and my life changed.

The living room of my suburban 2-bedroom apartment in Louisville soon became an immersive wrap-around console. In a sort of accidental sneak-preview of the bike that would follow a 15 years later, the machine was playfully dubbed BEHEMOTH (Badly Engineered Heap of Electrical, Mechanical, Optical, & Thermal Hardware)… with all sorts of features that would have made me rich had I any business sense at all. But working alone in Kentucky isolated me from the personal computer gold rush that was beginning, and I was having too much fun to think about marketing.

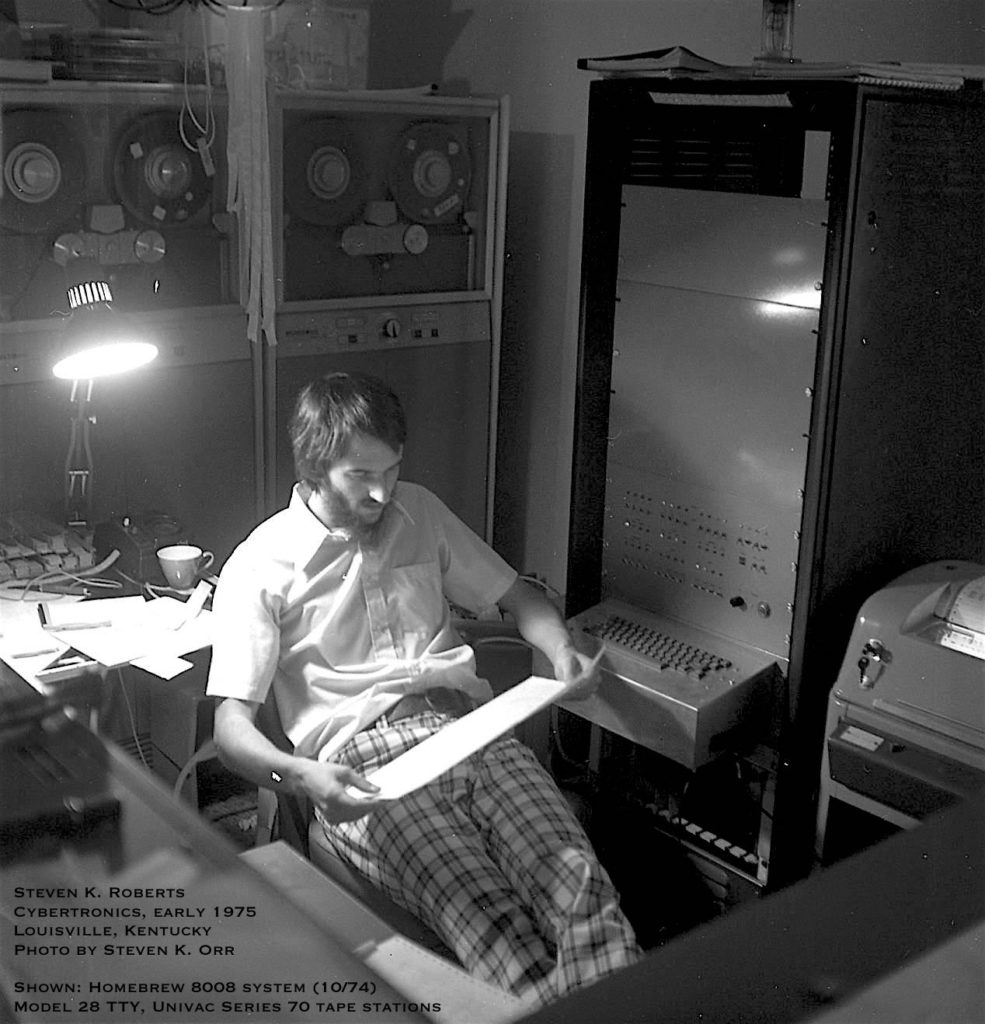

Here I was in early 1975, time stamped by those insane plaid pants:

The Univac Series 70 tape stations behind me were acquired with noble intentions, but I never did interface them to my 8-bit micro… I was using paper tape and later audio cassette for file storage. The Model 28 teletype was occasion for my first technical article, and a few weeks after the system flickered to life I wrote a text editor and started using the machine for correspondence and mailing-list management for my young company, Cybertronics. This was an insanely exciting time, and I threw myself into music synthesis, graphics, communications, and consulting… quitting the day job to eke out a living, turning passion into business.

☛ A Lifetime of Consoles ☚

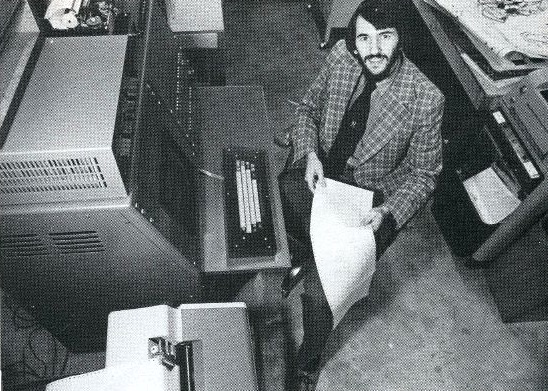

By 1976, I had acquired a gorgeous sloping panel rack with pull-out desk… and moved it to the local industrial park. Suddenly I was deep into industrial control engineering.

Jeffersontown Music & Writing Lab

Having space in an industrial park was great for credibility, and there was even room for employees and serious inventory… though the combination of having to commute was irksome. What I mostly wanted to do was play and then write about it. I think Cybertronics lasted about a year or two there, playing grown-up with a leased BMW and local business press coverage while still selling parts and surplus, running a half-assed computer store, and doing contract engineering. I was in my mid-twenties, spread too thin to have fun… showing up every day with fluffy black Cybercat and trying to be all things to all people.

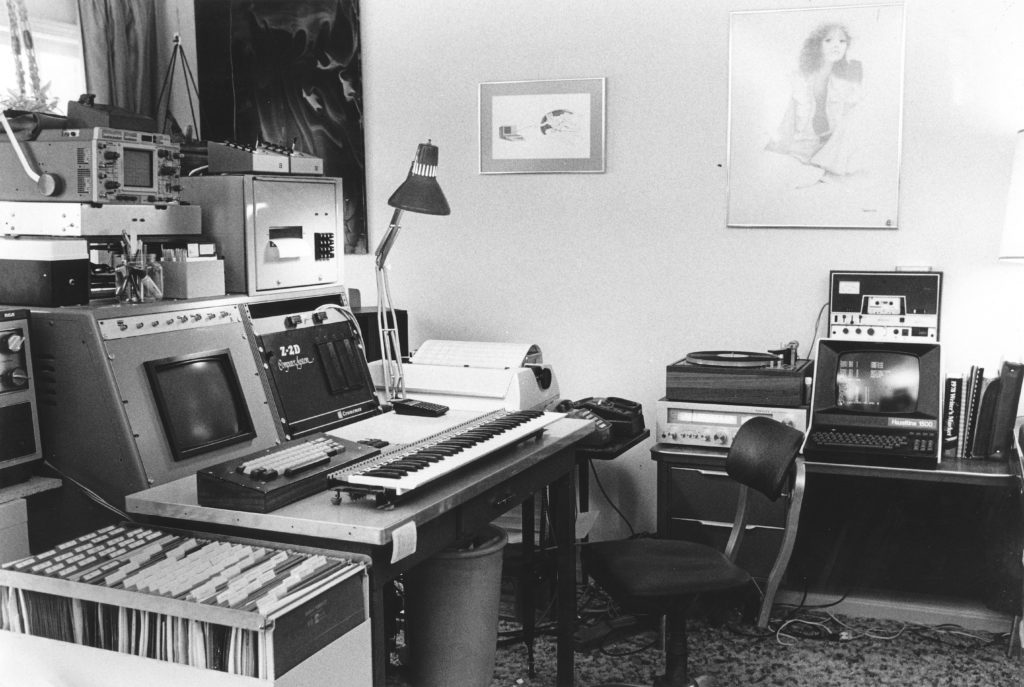

Enough! I rented a small house nearby and built a living-room lab optimized for writing, development, and tinkering:

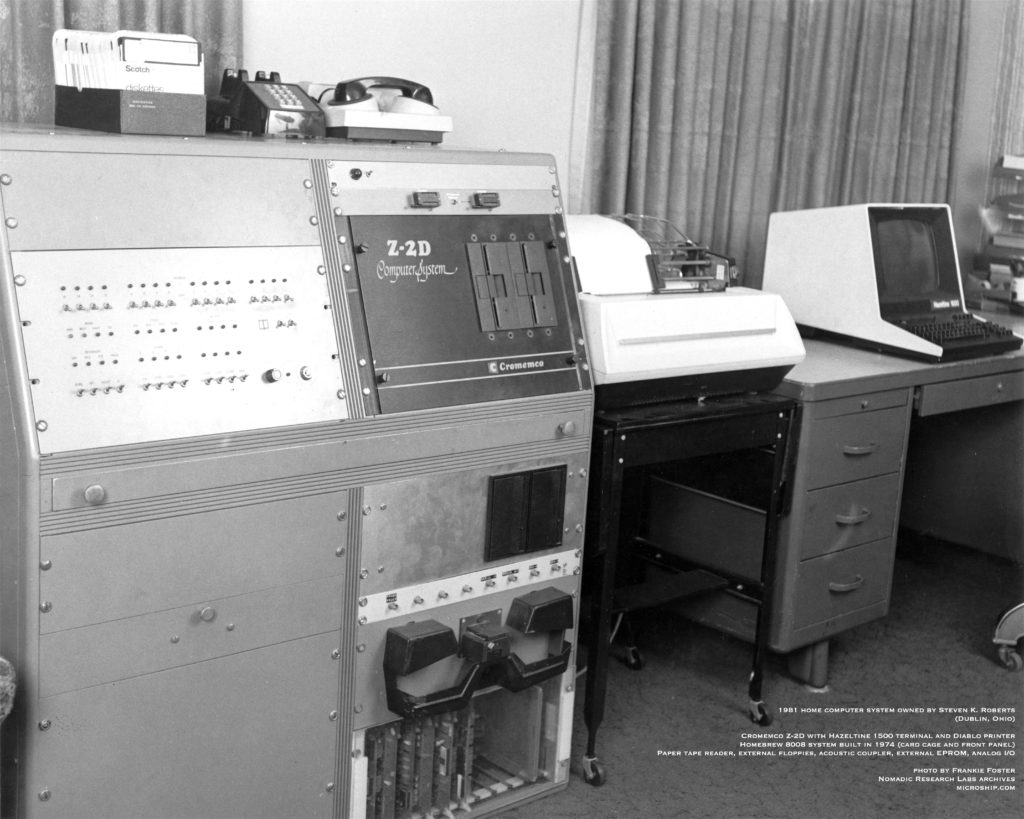

By now I was living in a Cromemco Z-2D with a custom memory-mapped display, polyphonic keyboard interface, sound modules, EPROM simulator for development, and other toys for myself and various clients. I gave myself a simple rule: every project had to spawn at least one magazine article, and there was no shortage of those… I was writing for Byte, Kilobaud, Creative Computing, Interface Age, Machine Design, and more. I phased out all of the Cybertronics business units except for consulting, started calling myself a writer, and got my first book contract.

This evolved into a phase with no console, but it was both dreamy and immersive… I bought a 13-room Victorian in Louisville’s Crescent Hill neighborhood, and over the next year immersed myself in engineering contracts for Corning Glass, Seagram’s, and Robinson-Nugent. The upstairs rooms were labs and shop spaces, and in retrospect this was one of those life epochs that could have gone on for a while, quite happily.

But one day a pesky Lambda power supply salesman dropped by and told me about a company in Columbus that needed a software engineer with my experience, and one thing led to another. I burned bridges and jumped ship, trucking all the machinery to Ohio where I bought the “three-bedroom ranch in suburbia” that inspired long-distance travel four years later.

“Where’s the Living Room?”

This epoch, complete with a short-lived but earnest attempt at family life, was the inhalation that launched my bicycle adventures. The job that inspired the move grew tedious, and less than a year after moving I quit… now chained to a mortgage on a suburban acre. Soon the place was a giant computer room with a kitchen off to the side, darkroom and lab down the hall, shop in the basement, and library everywhere. The sloping cabinet became the key component of my life’s seventh console:

The world was about to change completely, and that acoustic coupler was my initial connection… with a dedicated phone line connecting me to Source, DIALOG, SBC/Orbit, the occasional BBS, and eventually CompuServe. From 1981 to 1983 I wrote a college engineering textbook followed by a slim business volume about computers, started an information brokerage, had a couple relationships, and gradually came to realize that the American Dream was not working. Owning the desk didn’t make being chained to it any easier, and in the Spring of 1983 I decided to combine all my passions into a lifestyle… not mine them as businesses.

Bicycle Consoles

Most of this huge archive is about my computerized recumbent bicycle, so there is no reason to re-introduce that in this article about consoles… which the Winnebiko lacked. (There is tons of history about that first 10,000 miles, including full text of the Computing Across America book; basically, I spent a year and a half on the road as the first “digital nomad,” physical location irrelevant, maintaining a freelance writing/consulting business via a tiny solar-powered laptop and a connection to CompuServe.)

After that trip wound down in 1985 and I took an engineering job for 6 months, it was clear that I wanted to do it again… but this time with integrated systems and the ability to be productively connected while on the road. A bike with a console, now that would be the thing! I needed to be able to type while riding, control and monitor solar/battery power, run a packet radio BBS and other communication tools, monitor sensors, navigate, chat with my companion, secure the machine, and eventually add one of those newfangled cellular phones. In 1986, the Winnebiko II came to life, fine-tuned over the next two years as it covered both coasts of the United States:

Of course, this was not the canonical 19-inch rackmount… there were a few physical design constraints, being on a bicycle. But it was the perfect integration of my innate need to have an integrated equipment console mixed with the deliciously visceral lifestyle of pedaling an open-ended adventure. This machine felt like coming home, and another 6,000 miles flowed under my wheels.

The only problem was that it was architecturally inflexible, and editing with a soldering iron is sloppy. Technology was moving fast now, with new tools that I had to have… but every time I thought about adding things it was clear that it would involve major surgery. Time to take another approach.

BEHEMOTH, A Grand Turing Machine

The three-year project that began as Winnebiko III was, in retrospect, insane. With an estimated value of $1.2 million (including human time), this 580-pound, 105-speed “bicycle” veered into a whole different direction. The first two were about bicycle touring; this was about system integration and nomadic connectivity…

BEHEMOTH addressed the hackability issue by turning everything into resources that could be arbitrarily interconnected (long before there were proper ways to do that, like NMEA2000). The console carried a Macintosh screen that flipped up to expose a VGA display for the CAD system, the helmet had a heads-up display and ultrasonic sensors for cursor control, and there was a SPARCstation behind the seat for serious networking. A second console (19-inch rackmount) in the trailer was devoted to amateur radio and related things. Three FORTH controllers took care of resource management, the bike could talk, and there was a satellite earth station for Internet email. It was a beast.

Other than being a pain to pedal uphill and wrestle through motel-room doors, this contraption was absolutely delicious… and for a time, the perfect toolset. All my favorite toys had addresses in audio, serial, and power domains; simple FORTH programs could conjure novel configurations to accomplish things that would have otherwise been huge development projects. The media loved it, I had about 140 sponsors, the lab was sponsored by Sun Microsystems, and the volunteer team was such a pool of technological brilliance that I was constantly learning from the best.

But by now, 17,000 miles down the road, I was also getting tired of pedaling (and explaining) my complex heavy machines. I started fantasizing about porting the whole thing to water… especially after dating a Unix sysadmin who turned me on to kayaking. Oh my… now I have to make electronics work in a salt water environment. Not easy.

Nautical Dementia

A decade passed. The Microship project went through so many phases that they became a blur, with lab space hosted by UCSD and then Apple Computer. Like BEHEMOTH, this was an all-out technological effort that pushed everything else to the background. You can get a sense of the scale by reading about the decade of development.

The machine that eventually rolled out of the lab in 2002 was never fully completed; the fiberglass space reserved for its console was blank, even though most of the systems were working on the bench. The block diagram of the system shows the architecture, which included a multidrop network of multitasking FORTH nodes along with crosspoint switching networks for serial, audio, and video (click to embiggen):

But like many boat projects, by the time it was “done” I was starting to want something else entirely. By now I was 50, and the expedition lifestyle of living out of packs and sleeping in a tent was much less appealing than oh, maybe having a comfortable place to sleep and cooking facilities a level up from camping. Even though I had built a 3,000 square foot building for the Microship and spent a decade of my life chasing the dream, I was starting to think a nice sailboat would do the trick. You know, get in and go… with a diesel auxiliary to cruise along on the icky days.

A Touch of Nomadness

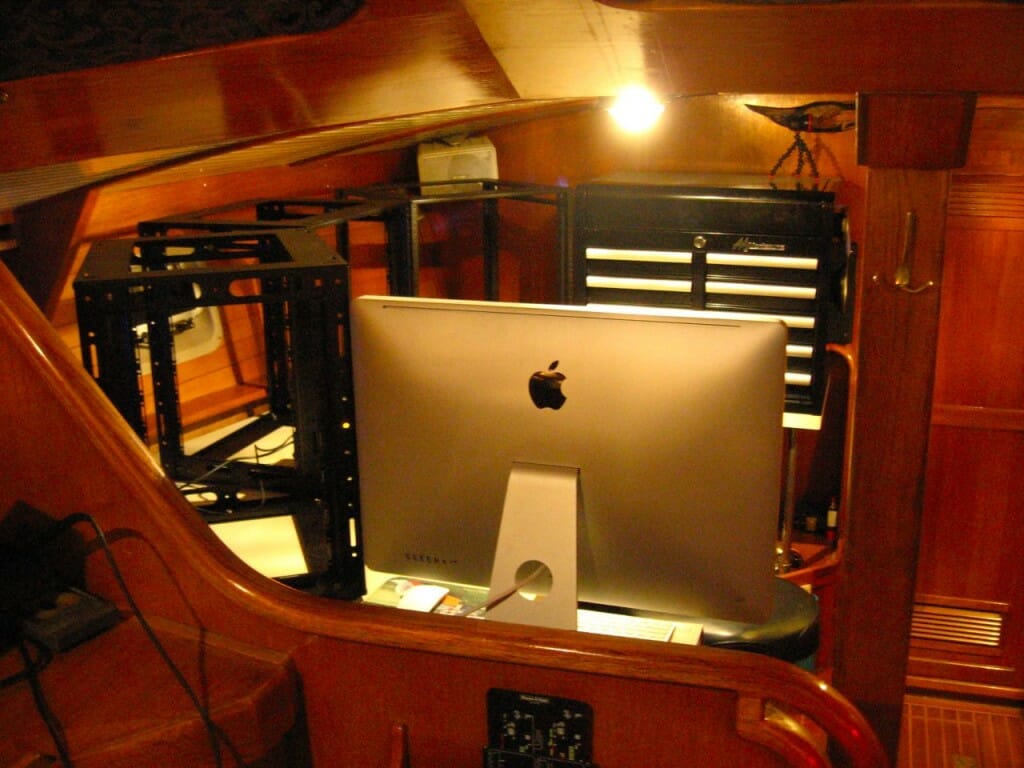

After a little 2006 side trip in “Microship on Steroids” (a 31-foot racing trimaran), I acquired an Amazon 44 steel pilothouse sailboat and went to work… similar concepts, better tools, more space. Of prime importance was the console, which would replace the dinette. Here’s that region, with three Middle-Atlantic CFR-12-16 rack cabinets mounted on a custom desktop integrated into the boat, with magnetic fixturing embedded in the laminate:

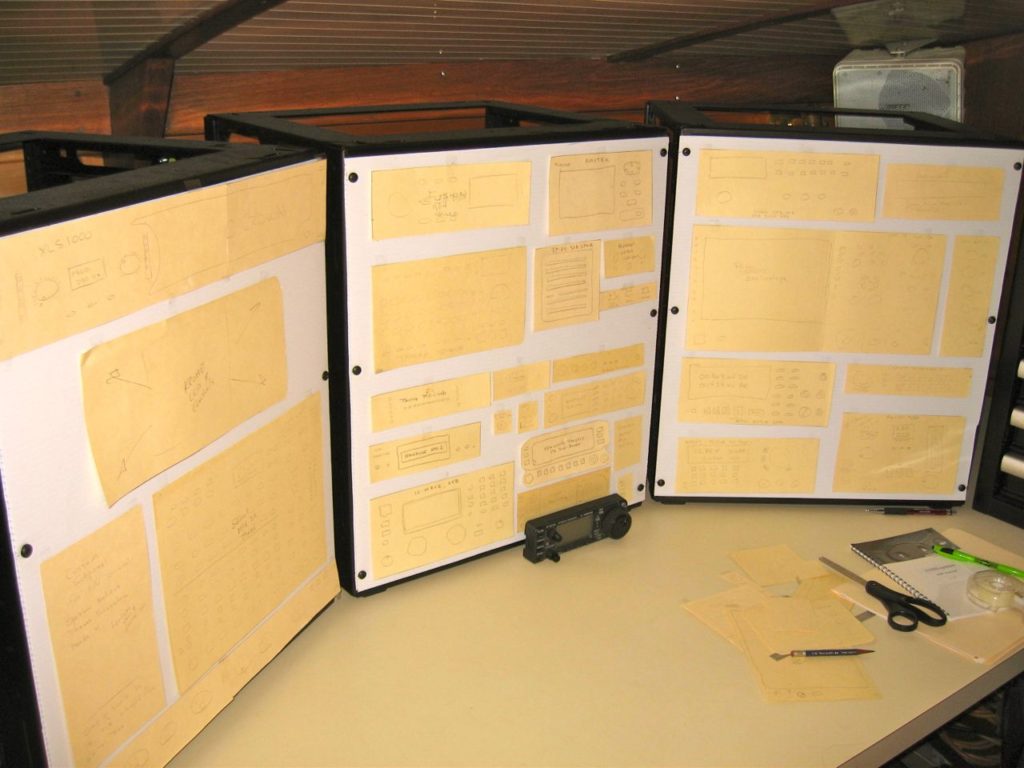

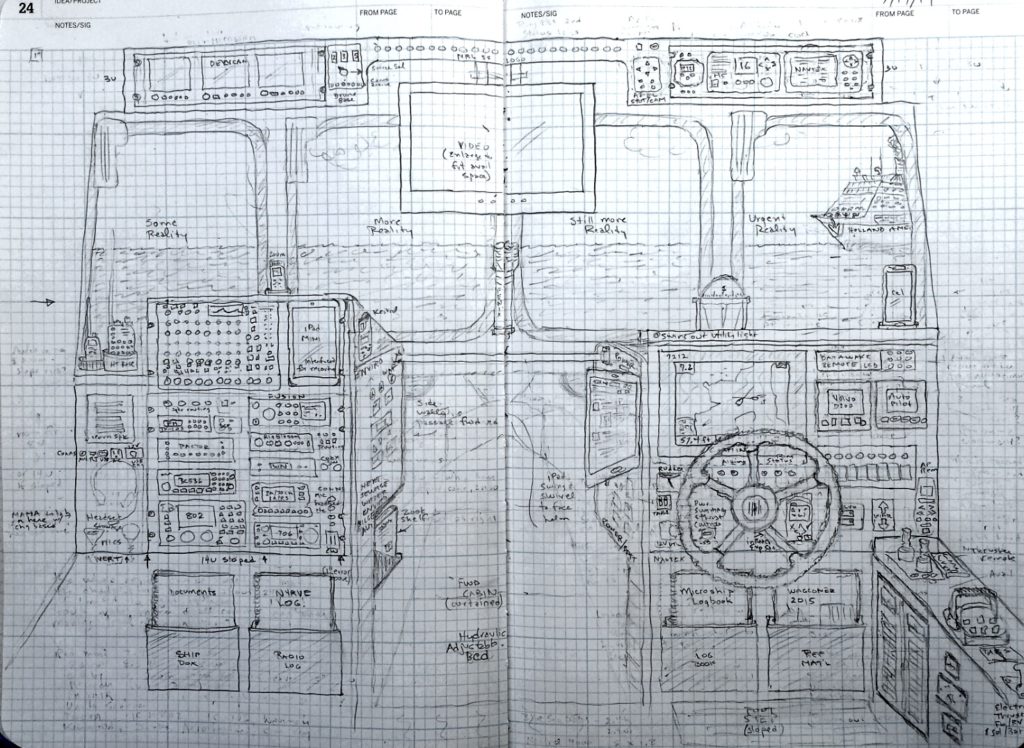

And this was where we were headed… a visualization model cobbled together with my CAD system (Cardboard-Aided Design):

But while all this was slowly plodding along, lab shelves filling with beautiful equipment ready to be panel-mounted, boat and life projects (including a sailboat power console) were gobbling years… and in 2015 I made the painful decision to sell Nomadness and cross over to the Dark Side. One of the motivations was to have space for a proper console, though I did go through a brief phase of thinking I could tightly cram everything into a Ranger 27 tug:

I got over that fantasy after spending a couple of days in one, and instead found a gorgeous 50-foot Delta that would be the perfect substrate.

Datawake

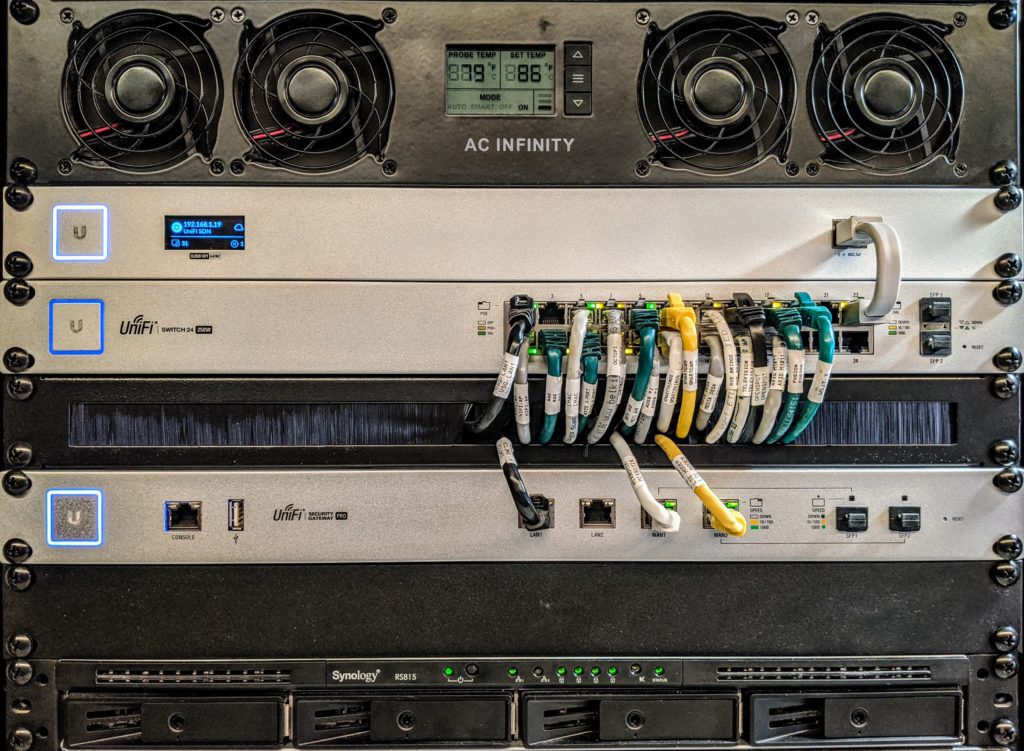

Ahhhh, space! After a sailboat, this was luxurious. I took delivery and moved aboard in February 2016. The very first thing I did after putting up curtains was extract all the furniture, giving me a 12×12-foot space in which to build my lab. I named her Datawake, envisioning a “wake of data” streaming behind, and dove at last into the project (pausing to build a machine shop into the “basement.”)

There is a very detailed article about the console on the server, breaking it down into the five cabinets (alpha-epsilon) and describing various packaging techniques. At this writing (2021) I have lived aboard this boat for five years, and the lab has been a solid toolset for audio production, amateur radio, design work, system monitoring, ship security, digitizing video, writing, and playing the retractable piano.

There was one huge design error with this system, though there is really not much I can do about it. The console backs up to the side of the boat, and there is no way to get back there for cable routing, cleaning, airflow management, or anything else. The cabinets are on Delrin runners (fixtured to the desktop when underway) and pull out easily, but doing maintenance of any sort is a lot harder than I expected.

Still, I can’t help but think that kid from 50 years ago would be thrilled to see what he would someday build into his boat… from end to end, the machines are blinky magic.

Harbor Digitizing

And that leads us to the final section (at least for now)… an unexpected life-fork that replicated itself like DNA out of the boat system. Back when I was that geeky kid, I occasionally got to watch my father’s home movies from the forties… enchanted by flickering images from when he was young, sailing, traveling, and even OMG OMG (with a surreptitious glance over at tight-lipped mom) was that a previous girlfriend? These reels sat in a huge box for decades, and became mine when Edward died in 2005.

I researched the digitizing options for years, and that was so daunting that I decided to do it myself. Naturally, the process involved huge learning curves and obsessive fine-tuning, so at some point I thought I’d amortize the $10K or so in equipment by doing it for other people. The biz grew… added video and audio tapes… refined processes… increased resolution… inspired learning… set up a mirrorless copy station for slides… became an LLC… documented processes… added employees… yikes!

I’ve mined a few bits of the Datawake console to flesh out the one at Harbor Digitizing, humming away in Friday Harbor (where I live aboard in the marina). I do the 600-step commute most afternoons and fill amazingly high-density thumb drives with peoples’ histories, while continuing to fine-tune the tools and write a book about the methods of using them.

After this tale spanning over a half-century, it is strange to recall the impact of that day in the avionics shop. A geeklet experienced a “love at first sight” moment, knowing it would be important but having no idea where it might lead. When I started this post, I envisioned it as a dozen quick photo/captions since I had just found the shot of my teen equipment rack; I didn’t expect an all-day voyage along a lifetime, threaded together by glimpses of 19-inch rackmount consoles and held together by 10-32 screws.

How publishing has changed in a mere two centuries… After scanning an ancient book from my family archives, I wrote a title page for the above:

☛ A Lifetime of Consoles ☚

BEING

a languid stroll through myriad Shrines of Geekery at which the author hath toiled over decades of exploration and invention, to the exclusion of life’s Proper and Fundamental Purposes

INCLUDING

artistic renderings and diagrammatic representations

THE WHOLE

intended to inspire reminiscences and memorialization by Readers suffering similar obsessive afflictions and affinity for signaling lamps

TO WHICH IS ADDED

linkages of the hyper kind to Texts describing Machines of Thought, equipped with electrical wires for correspondence with distant lands

You must be logged in to post a comment.