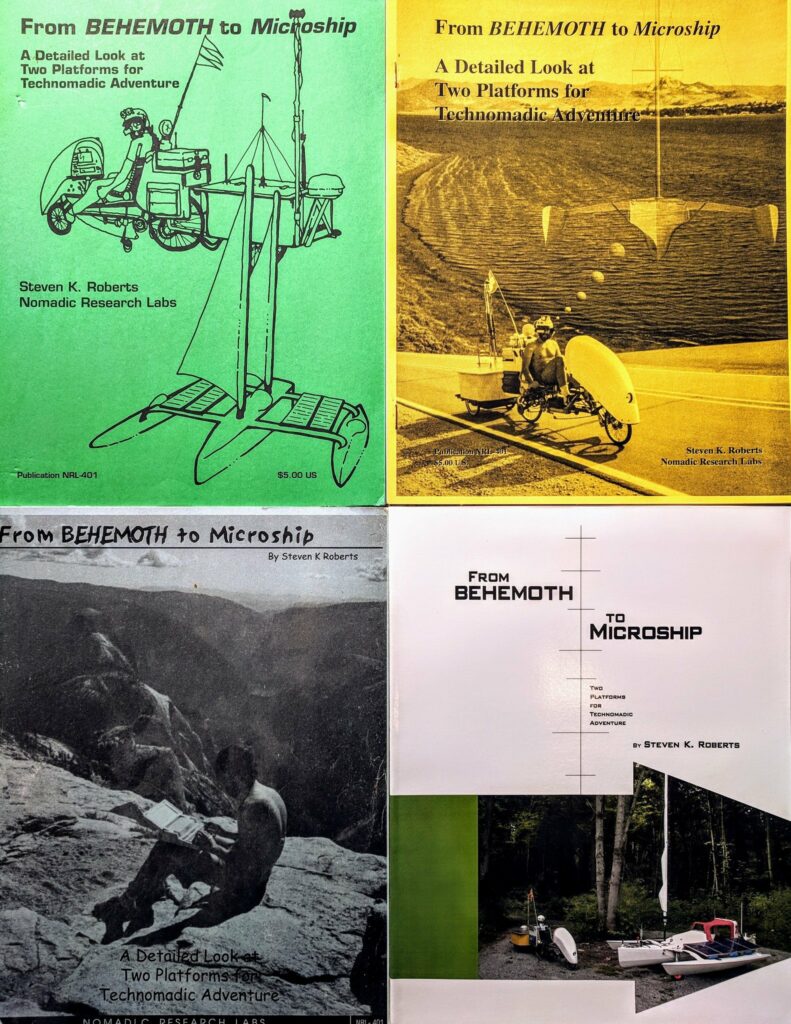

A Decade of Microship Development

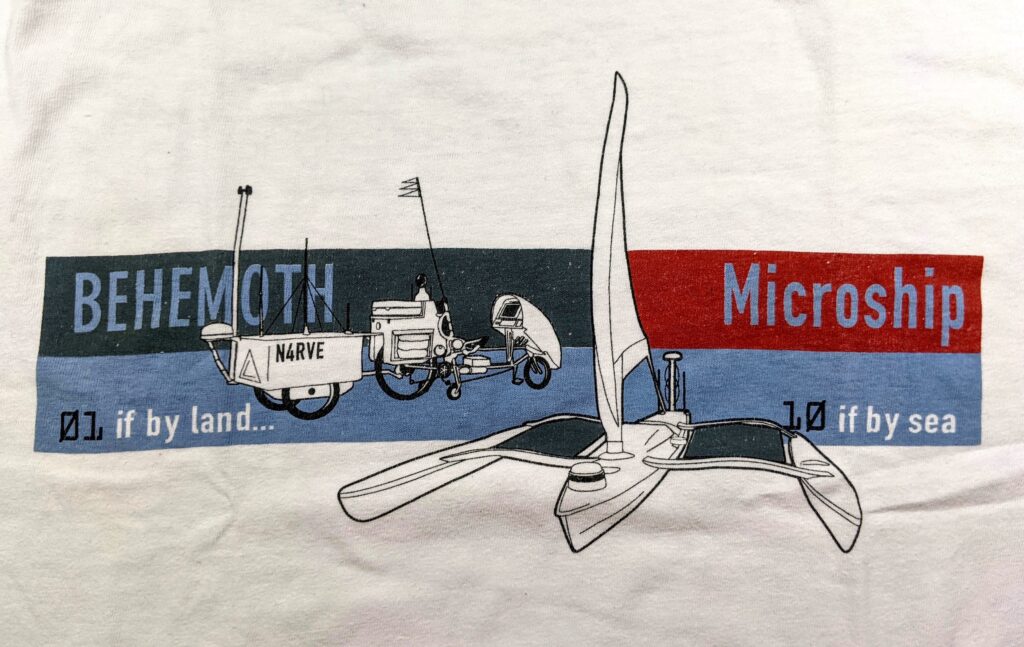

“Like BEHEMOTH, but with hulls. How hard could it be?” (1993-2002)

by Steven K. Roberts

Nomadic Research Labs

“Exhilaration is that feeling you get just after a great idea hits you, and just before you realize what’s wrong with it.”

—Rex Harrison

A clear fantasy in no way implies a well-defined course of action. One of the great recurring tragedies of engineering is the disparity between the two—the ease with which you can fling yourself along a path that seems obvious and correct, only to discover that the real goal is poorly understood, irrelevant, or changing so fast that you become “staggered by your own imagination” (Thanks to Dave Wright for that annoyingly insightful turn of phrase). I thought I was plunging into a quick one-year project, porting the bike concept onto something that floats. How hard could that be?

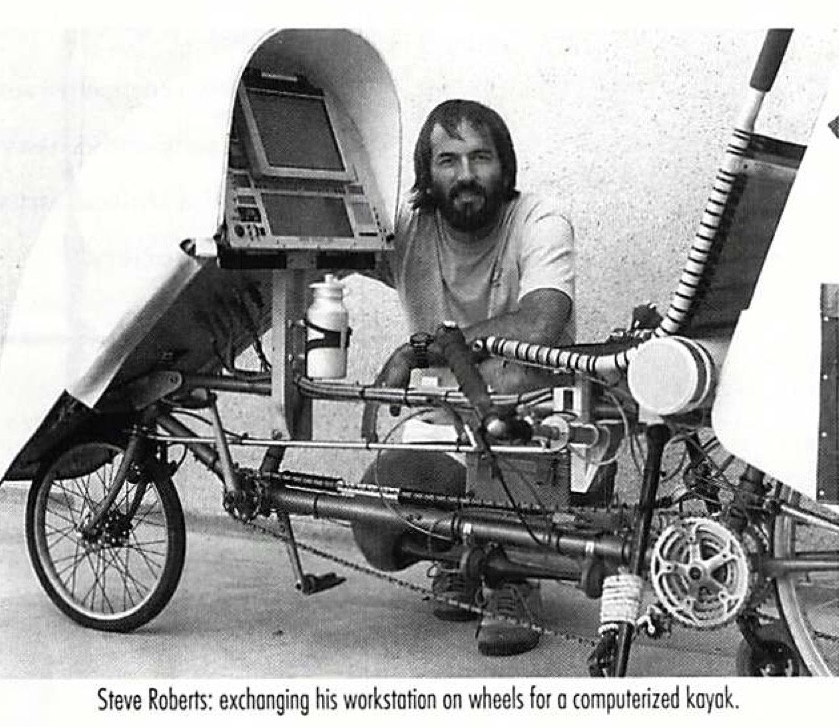

The Onset of Nautical Dementia*

It was 1992, and I was on the road… but driving the Mothership instead of pedaling. As the BEHEMOTH expedition receded in the rear view mirror and I trundled around the country doing speaking gigs, my life became defined by a deliciously mad fantasy of aquatic adventure… a full-scale technomadic overlay onto a tiny nautical substrate, elegant and swift. I wanted the bike, but with hulls. Kayaks filled my head, and before long I had acquired my own—complete with an overhead stowage nest across from BEHEMOTH in the Mothership, the 20-foot mobile lab trailer in which I plied the Interstates while schlepping the bike into hamfests, trade shows, user group meetings, and corporate brown-bag luncheons. The more I talked about the bike, the more I thought about the boat.

* (thanks to Dave for that one, too.)

My world view was changing: for the first time since the Winnebiko days, I was focused on the adventure more than on the tools. I would wander into chandleries and browse nautical chartbooks, longingly, one page at a time, my mind flowing over seductive benthic topography while I imagined probing estuarine crevasses heavy with the funk of low tide. Boats themselves became almost erotic in my imagination; while numbly piloting Biggus Truckus across the prairies, the other 90% of my mind would lose itself in daydream scenarios that commingled flesh-strewn beaches with environmental telemetry and underwater video, forging an obsession every bit as potent as the one that had propelled me out of Ohio.

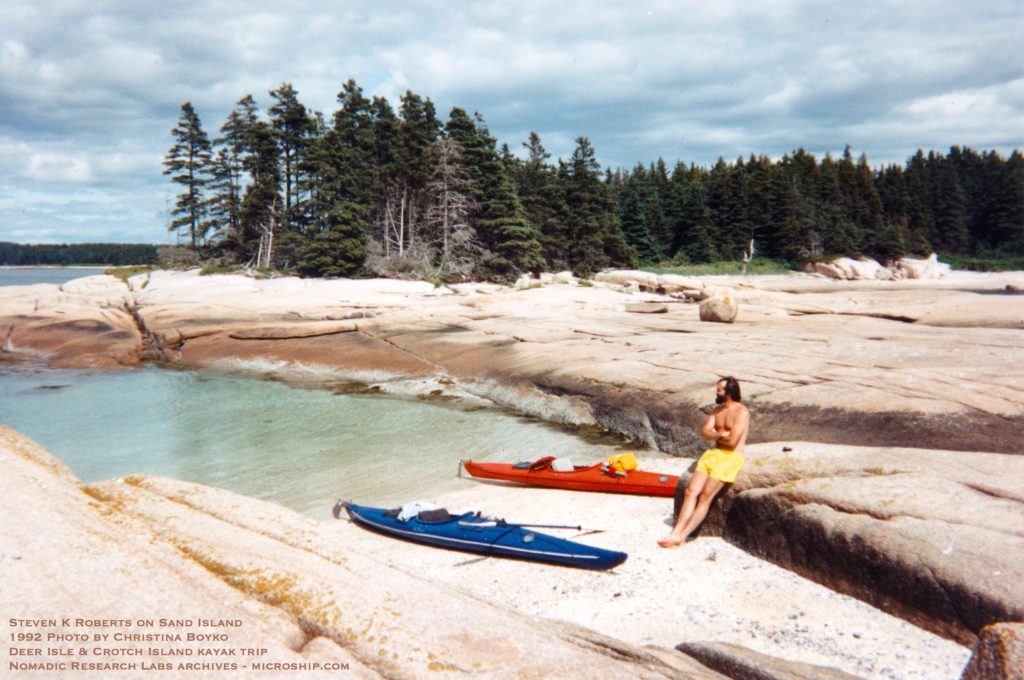

Alone and with various companions, I slipped my slender hull into every body of water I came across. I paddled Barclay Sound, Ole Muddy near a freeway overpass in Iowa, the Petaluma River, Jetski-infested Shasta Lake, sparkling-cold Lake San Cristobal high in the Rockies, Puget Sound, the Maine coast around Deer Isle, San Diego and San Francisco Bays, surfy Santa Cruz (whoa!), Lake Michigan amongst the slushbergs, mangrove canals in the Florida Keys, even a placid man-made pond at a Nebraska campground—whenever the random peregrinations of the BEHEMOTH dog ‘n’ pony show would land me near water, I’d go for it in the name of research. I hit both the East and West Coast Sea Kayak Symposia, schmoozing with the industry, fast-tracking learning curves, and gathering gear. The plan was simple: I’d acquire a big fat kayak with lots of room, build a pressurized console to house the electronics, tile the deck with solar panels, pack up, and get going by the Spring of 1994!

Behemoth, in the Old Testament, a powerful, grass-eating animal whose “bones are tubes of bronze, his limbs like bars of iron” (Job 40:18). Among various Jewish legends, one relates that the righteous will witness a spectacular battle between Behemoth and Leviathan in the messianic era and later feast upon their flesh. Some sources identify Behemoth, who dwells in the marsh and is not frightened by the turbulent river Jordan, as a hippopotamus and Leviathan as a crocodile, whale, or snake.

— Copyright 1994, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

I initially dubbed the project LEVIATHAN to echo the acronymic moniker of my bike, although it did vaguely occur to me that maybe this wasn’t the philosophical precedent that should color the new design… I wanted the boat to be light and sleek, with no more on-board gizmology than the basic tools required to make my dream come true.

The first task was finding a place to park Nomadic Research Labs and get to work. As usual, I was budget-limited, so holing up somewhere and renting facilities was out of the question. I fired off email to contacts all over industry and academia, questing for a spacious place to sling goo, fabricate electronics, and write some code—rather a lot to ask (especially the goo part, as companies tend to be sensitive about organic solvents and other toxic chemicals in the work environment). Not too hopeful about that option, I investigated old barns, derelict urban buildings, boatyards, manufacturing or warehouse space lying fallow, decommissioned military sites, university agricultural sheds, and even the wild idea of parking the Mothership in my dad’s field in Kentucky and taking over the basement. I was getting frustrated.

An Academic Sojourn

One day in the Spring of ‘93, I arrived in San Diego to speak at Qualcomm, one of my favorite sponsors—the creators of the bike’s satellite communication system and gurus of CDMA and other DSP-flavored wizardry, a company founded and managed by engineers instead of business majors. A friend there pointed me to nearby Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where I might have a chance to pick up a few tricks from guys who know how to keep electronics working at sea (a non-trivial problem, with all that delicate high-impedance circuitry surrounded by conductive aqua regia). Armed with an introduction, I wandered over and did a casual bike show ‘n tell for a Friday afternoon Scripps cookout.

Now, I’d never spent much time around Real Scientists. As I was standing by the keg nursing a pint, my bike parked a few feet away and the surf pounding just beyond, a classic Hollywood stereotype of the brilliant young PhD walked over and said, “Fascinating. Have you gotten any results yet?”

“Well, I’ve fallen in love a few times,” I answered.

He looked at me blankly for a moment and then cracked up. “No, seriously…”

This was my introduction to academia. I hung around a few days, seeking space at the Scripps facilities, eventually managing to arrange a secure place to park the Mothership and stash my gear in a run-down storage facility in a desolate nearby canyon… but with no net connection, phone, or actual workspace. It was an excellent toehold, though, and the chain of contacts kept growing as I explored the couch circuit. A few days later I met with Professor Clark Guest in the Electronic & Control Engineering department at UCSD (University of California, San Diego)—that huge university just up the hill from Black’s Beach in La Jolla.

Almost immediately a potential win-win emerged. Although it wasn’t widely viewed as a problem among the academics, there was a serious shortage of hands-on engineering opportunity for students: they could make it through four years and get an undergraduate degree without ever picking up a soldering iron. I found this shocking, of course, and had a solution to offer: “Hey, give me some lab space and I’ll teach a senior projects class!”

I stumbled into the university culture with naiveté and an utter disregard for hierarchies—to me, there was no essential difference between deans, chancellors, TAs, and professors. Only much later did I understand that there is a pervasive caste system, which explained my tendency to ruffle feathers. Other than holding on to lab space long enough to get the Microship built, however, I had no pretensions of a career, publishing in refereed journals, or chasing the holy grail of tenure.

Nor did I anticipate the complex politics of space wars. My first lab was an abandoned bookstore… but the day after I installed a monitored security system and set up a working facility, a construction crew hacked straight through the drywall, knocked over a shelving unit, looked around in annoyance at my stuff, and asked me what the hell I was doing there. “We’re tearing out this whole end of the building and you gotta get this crap outta here NOW, before our contract penalty clause kicks in and costs us a thousand bucks a day. Which is what it’s gonna cost you.” But this disaster turned out to be tantamount to a back door from the institution-hacking perspective: now that finding space for me could be defined as an emergency, I landed within a few hours in the Microwave Lab, vacant for the quarter and perfect for my needs.

I moved out two years later. Occasionally real professors would wonder aloud what some rube without a degree was doing with 800 square feet of prime space in the engineering building, complete with a dozen benches, adjoining office, and Faraday cage. “I hear he’s having those kids build circuit boards. What the hell does he think this is, a vo-tech school?” But I was fortunate to have three faculty members solidly on my side (coincidentally, the only ones who had worked in industry), and was bolstered by a well-publicized program that gave students the chance to design and build real systems, not just run SPICE simulations as an antidote to the textbook world of lumped constants and zero-rise time pulses..

— much .edu about nothing —

The experience did cure me of any lingering wistful regret about having missed those idyllic college years, despite sampling a mosh pit during a Skankin’ Pickle concert and the daily consumption of epicurean cafeteria fare. All around me, students were undergoing a sort of extended agony of uncertainty and stress, many of them deep into engineering school without any notion of what real engineers actually do. Summers and holidays were bleak, with the local espresso spigots shut down or severely curtailed, and La Jolla has to be the most sedate college town I’ve ever seen (and I’ve seen quite a few, as the 10,000-mile solo phase of my bike trip became a sort of collegiate connect-the-dots exercise once the social opportunities became evident). But what mattered now was assembling an effective student team every quarter, learning how to be a manager, and getting on with the project. I hoped I’d be able to identify and attract folks on the fringe, give them interesting design challenges, and leverage their work to propel myself into the next adventure.

Despite the distraction of that 3-mile long nude beach just down the hill <swoon>, I dove in with passion. The Microship project was underway at last.

Microship 1.0—Kayak Hacking

The energy was relentless during that summer of ‘93, as I got ready for the start of the school year. I posted Microship Status Reports to a growing mailing list of volunteers and observers, spent my days on the horn with sponsors and nautical experts, prowled the diverse San Diego maritime community, and ravenously devoured trade journals and boat publications. I signed up at the Mission Bay Aquatic Center and took every class they offered, riding the bus from campus 3-4 days a week to sail Sabots, Holders, Lasers, Hobies, J-24s, and sailboards, all in the name of research. My notebooks bulged with sketches and rambling design narratives, and the concept began to take shape with the immediate goal of breaking it down into quarter-sized projects scaled to teams of 2-3 students.

Already the nautical design was evolving. Despite my fundamental belief that this had to be a lightweight, human-powered platform, it had become obvious a couple of months earlier that a kayak alone wouldn’t do the job. During a solo jaunt from Seattle to Blake Island, a perfect sunny day morphed within the hour into a grim death march of chill winds and ugly drizzle. I hadn’t yet learned to pay attention to NOAA weather broadcasts when conditions looked benign, and was out there dodging freighters in the rain clad only in T-shirt and shorts, my life jacket Bungeed to the afterdeck. A beautiful Kokatat polypropylene jacket and Gore-Tex outer shell were stuffed in a dry bag a few feet away in the forward gear hatch (yeah, I know, that was a stupid place to put them). The only way to reach insulation would be to capsize, do a wet exit into hypothermia-inducing water, swim forward, retrieve the gear while soaking it in the process, deploy the paddle float, re-enter the boat, pump out, shiver miserably for a while, and continue on my way. Obviously that would be silly, so I paddled my ass off until I hit the island, chilled to the bone and depressed about the whole idea. Why take off on an open-ended journey in an unstable boat with inaccessible gear? Hell, just handling the man-hour extension facility is a pain in a kayak, much less getting at video cameras, tools, or computers.

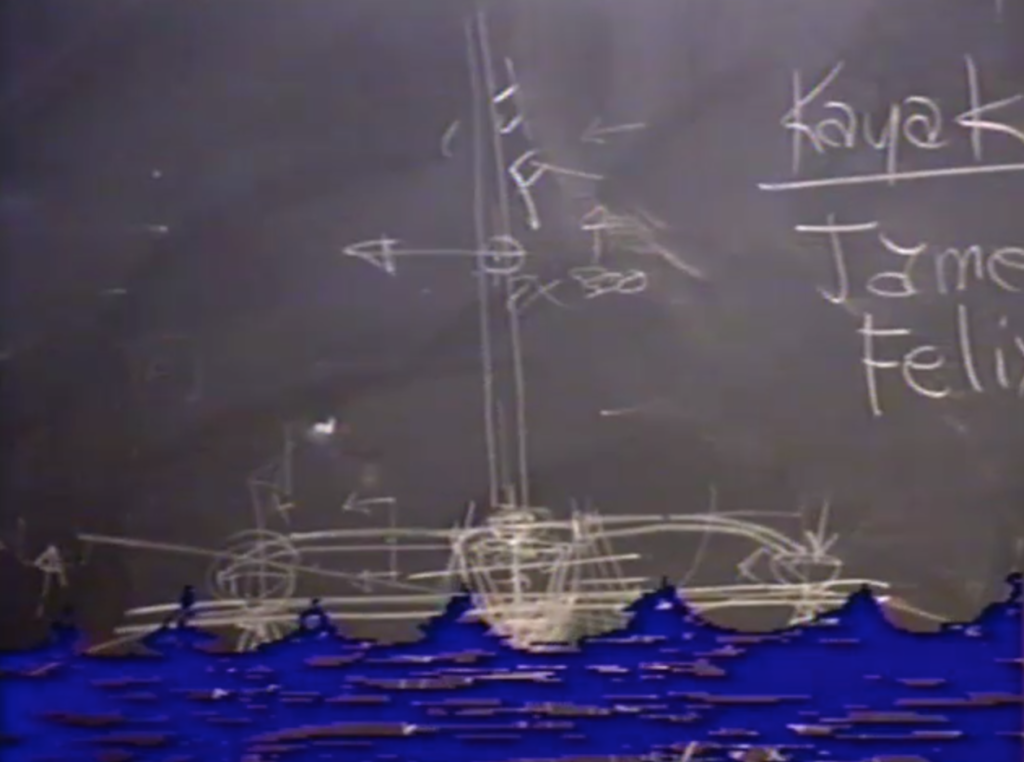

Clearly, it’s more sensible to build a catamaran with two kayaks (a kayakamaran?), or perhaps even a trimaran made of three. Not only would this provide enough stability to allow free movement around the boat, but there would be room for a solar array scaled to power an electric thruster. Hmmm… with multiple hulls providing righting moment, there’s no reason not to add a sail rig…

And so the plan, as I readied myself for the influx of UCSD students, was to build a little trimaran with the largest two-person kayak I could find as the center hull, linked by crossbeams to a pair of sleek singles serving as stabilizing outriggers and detachable play-boats. This would require considerable deck surgery, but would take advantage of off-the-shelf hardware—for life is too short to re-invent the hull. I envisioned a central control console, and set to work designing on-board systems.

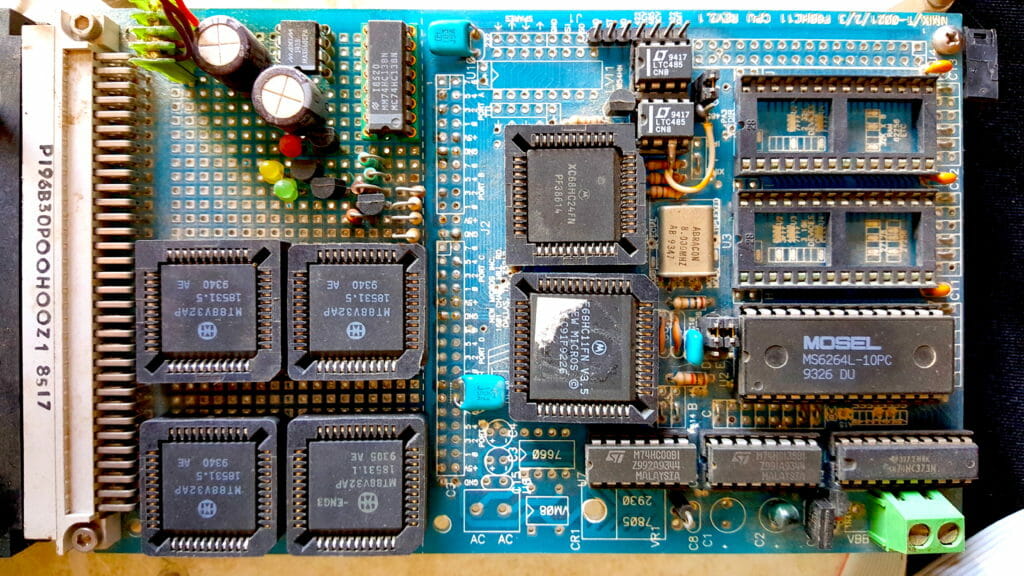

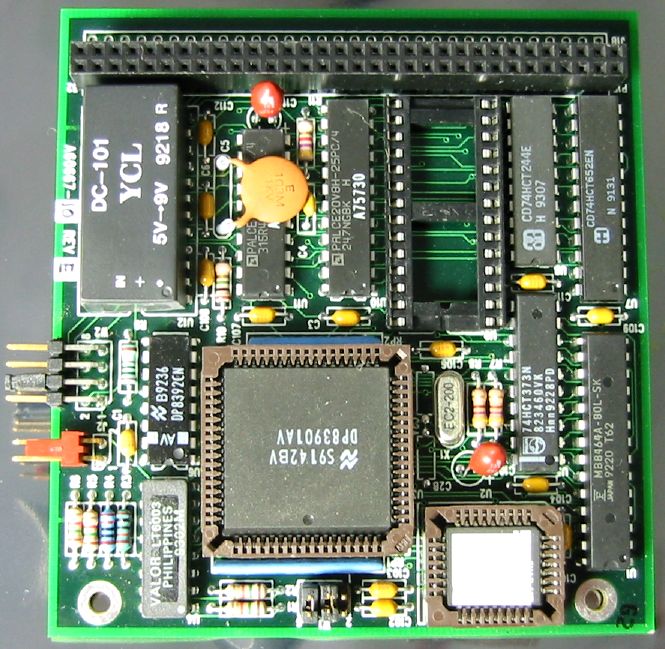

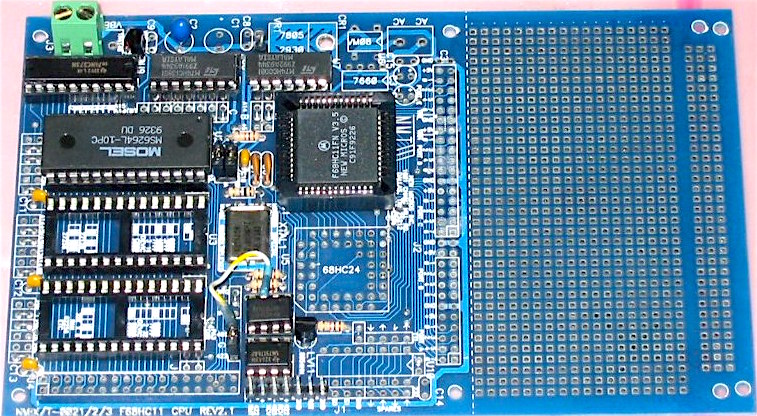

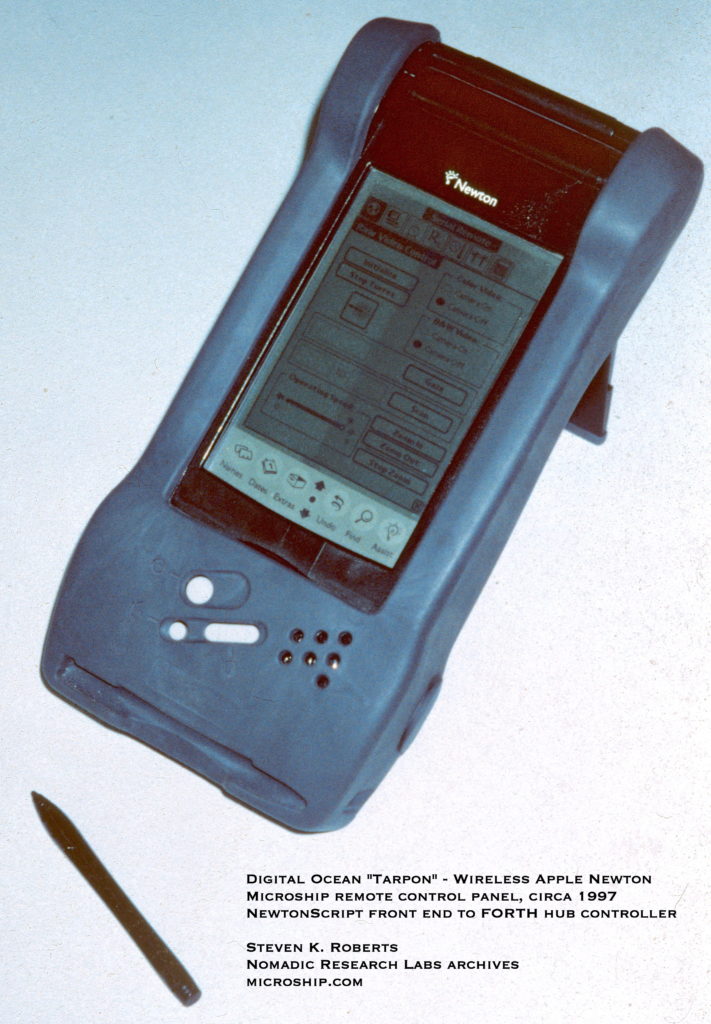

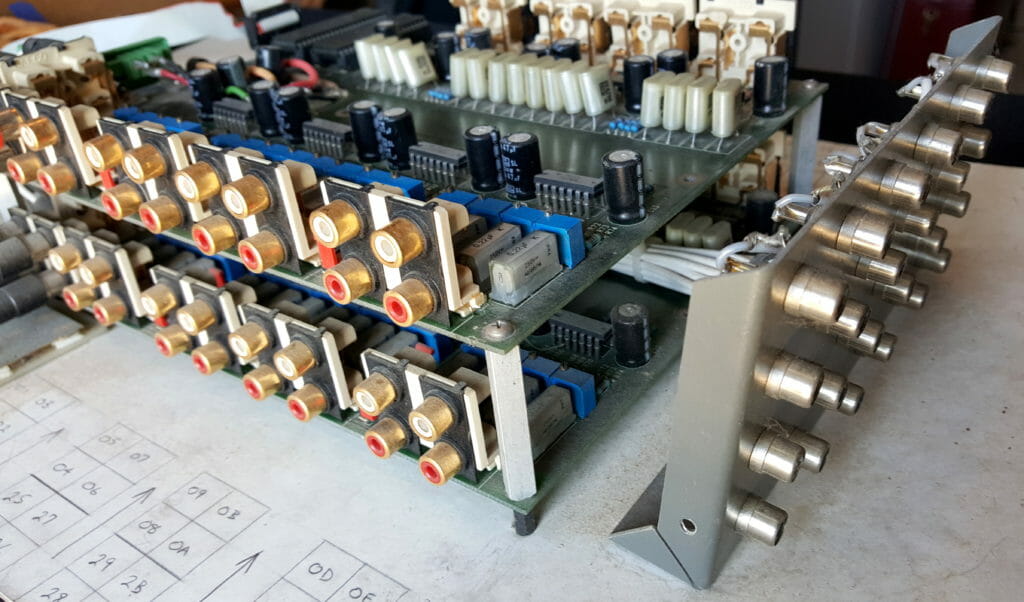

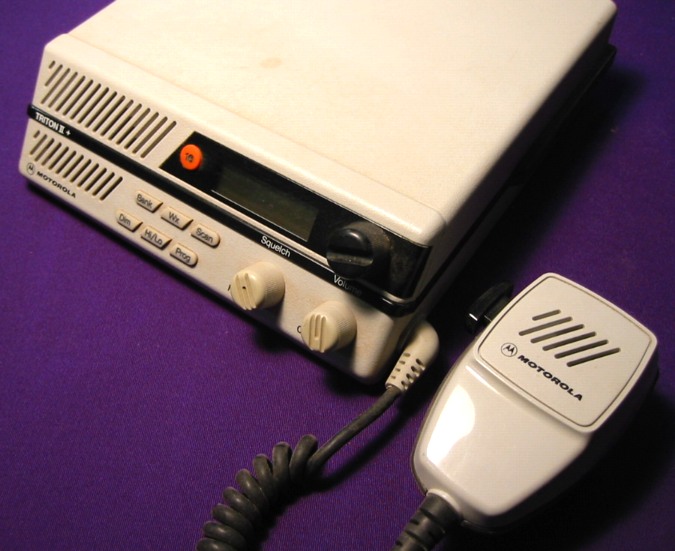

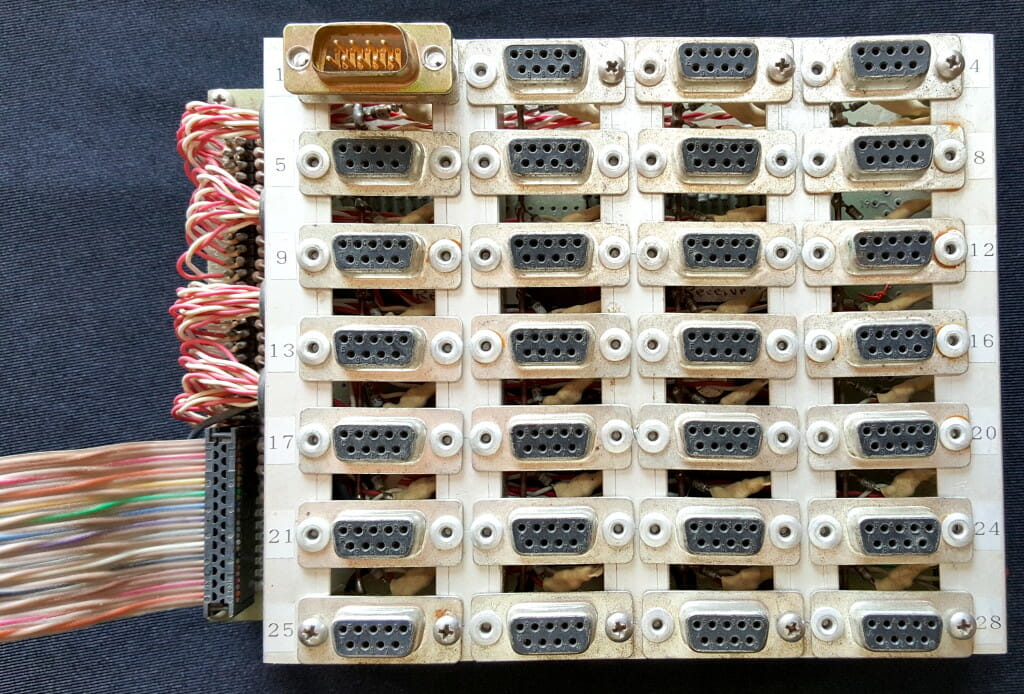

One of the best features of BEHEMOTH had been the crossbar networks that allowed anything to connect to anything, so I decided to replicate that on the boat… such resources as marine radio, cell phone, sensors, video cameras, ham equipment, nav tools, speech synthesizers, and stereo system would need to be infinitely interoperable. Some kind of low-power processor, perhaps a hacked laptop, would serve as a graphic front end, and the various local tasks would be handled by distributed network nodes. I had already gotten to know the 68HC11 with FORTH in ROM from New Micros, and discovered that they were in the process of developing a multidrop scheme that would allow up to 256 boards to hang on a single network. (Remember, I had an unusual design constraint: the need to modularize the entire system for parallel development by student teams of varying competence. It was also 1993; any processor robust enough to do everything would be too power-hungry to leave on all the time.)

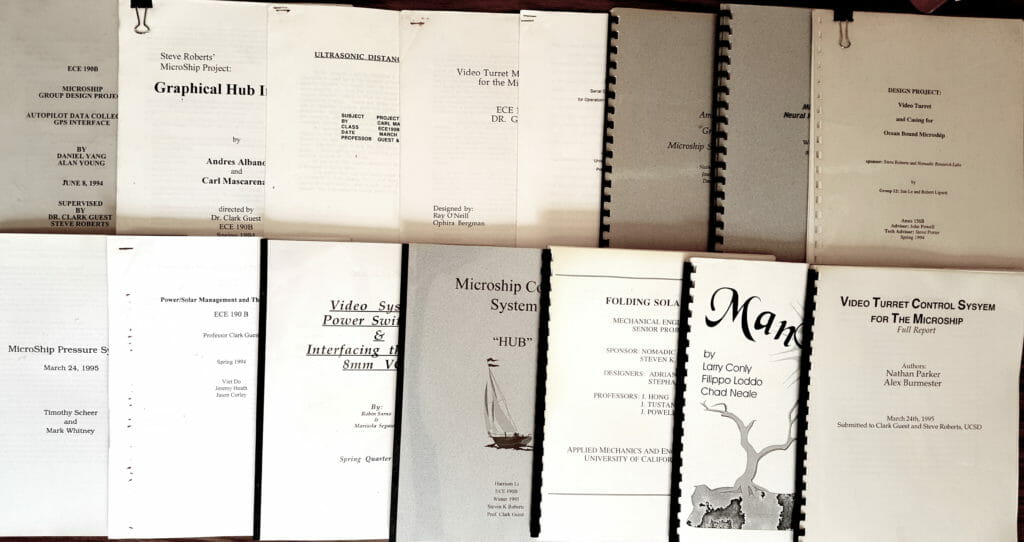

By September, I had completed a Microship Project Catalog, breaking the machine into somewhere around 45 tasks ranging from solar-panel packaging to front-end software. It was an optimistic document, with quite a few of the jobs requiring substantial skills and facilities, but it did give us a good starting point. When the first class arrived and sat timidly awaiting their fate, my professorial partner and I dove in, teaching FORTH, explaining the hardware platform, and assigning project teams.

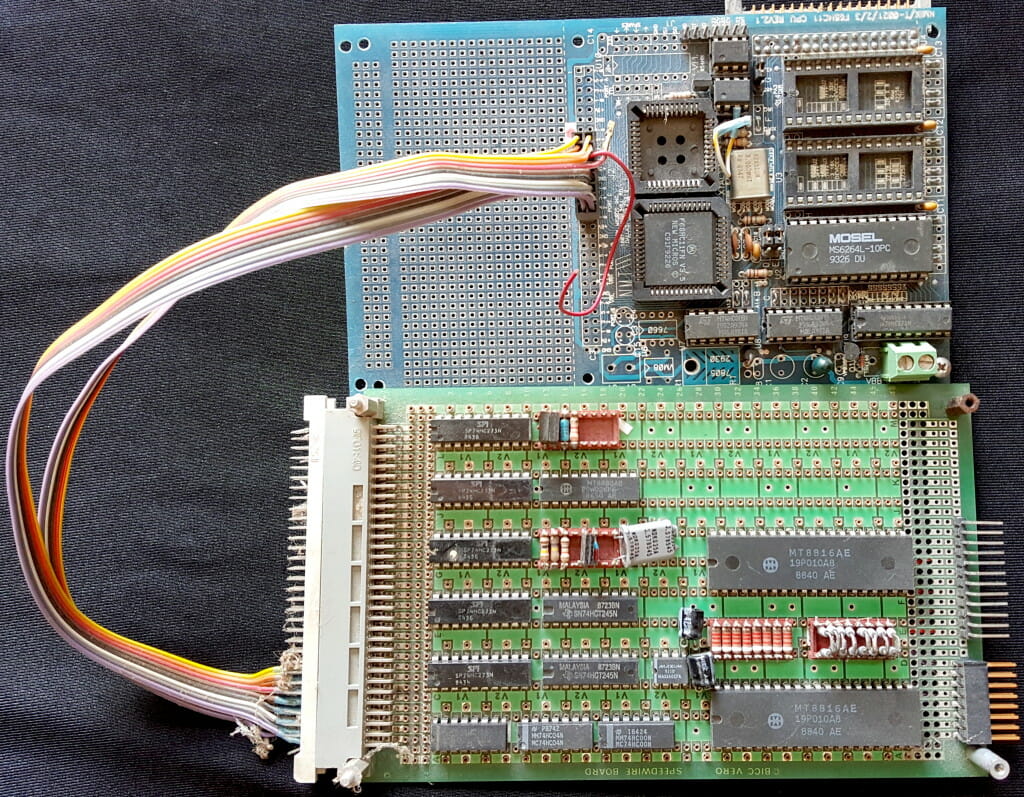

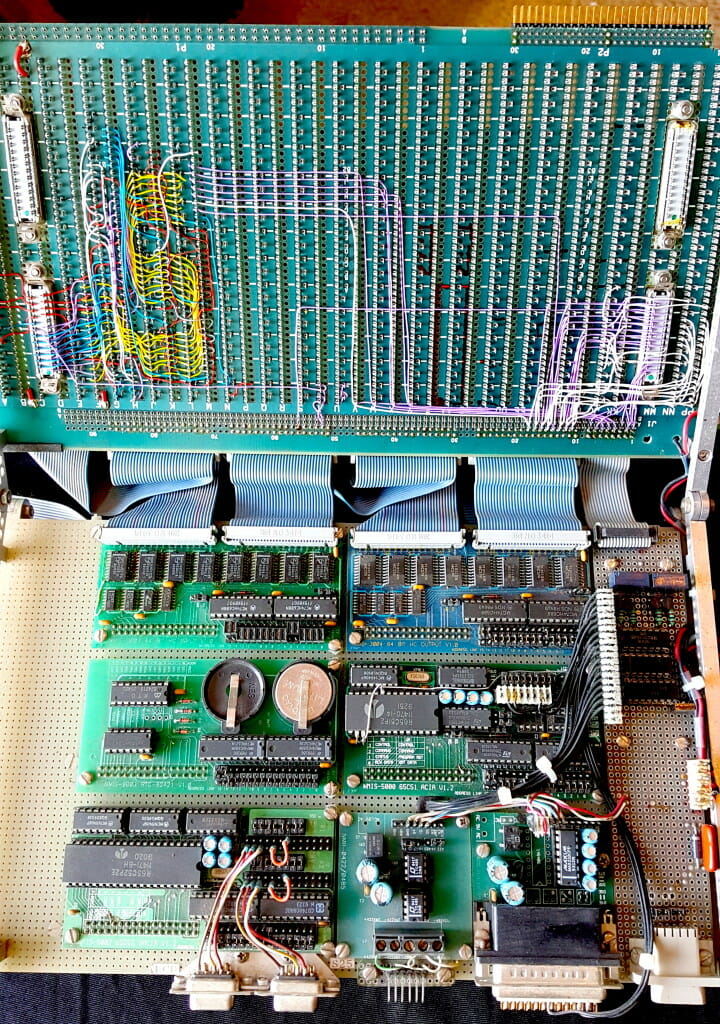

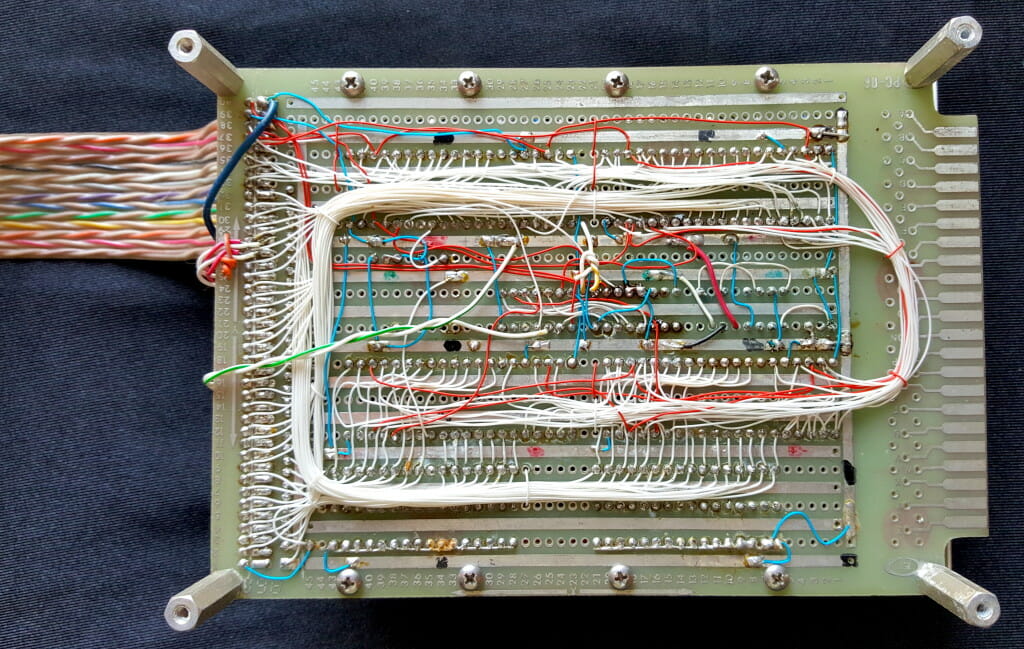

These were exciting times. In a few months we had about ten FORTH nodes scattered around the lab on benches arranged like finger piers in a marina, all chained together into a classroom-scale Microship emulator by a braided 6-wire bus and running the Beeline protocol designed for the project by Bill Muench (giving us pier-to-pier networking). Any node could be selected from the Hub using the HC11’s “address mark wake-up” broadcast, whereupon the lucky guy’s RS-485 transmit driver would be enabled to establish a one-to-one connection at a blazing 9600 baud. As the quarters passed, we wrote the code to download and launch applications, display node status, mirror local variables from individual nodes in the Hub (another FORTH board, but with more memory and lots of I/O), and recover from crashes.

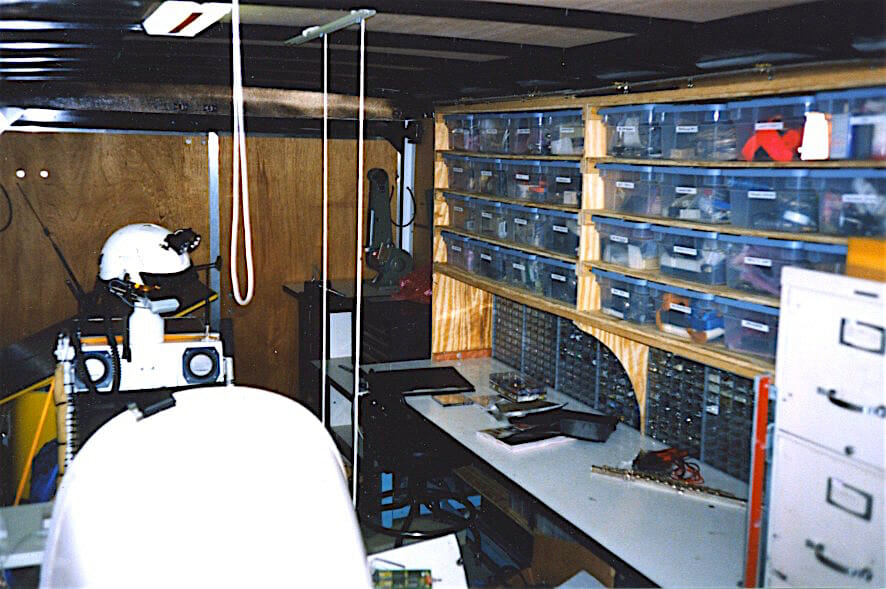

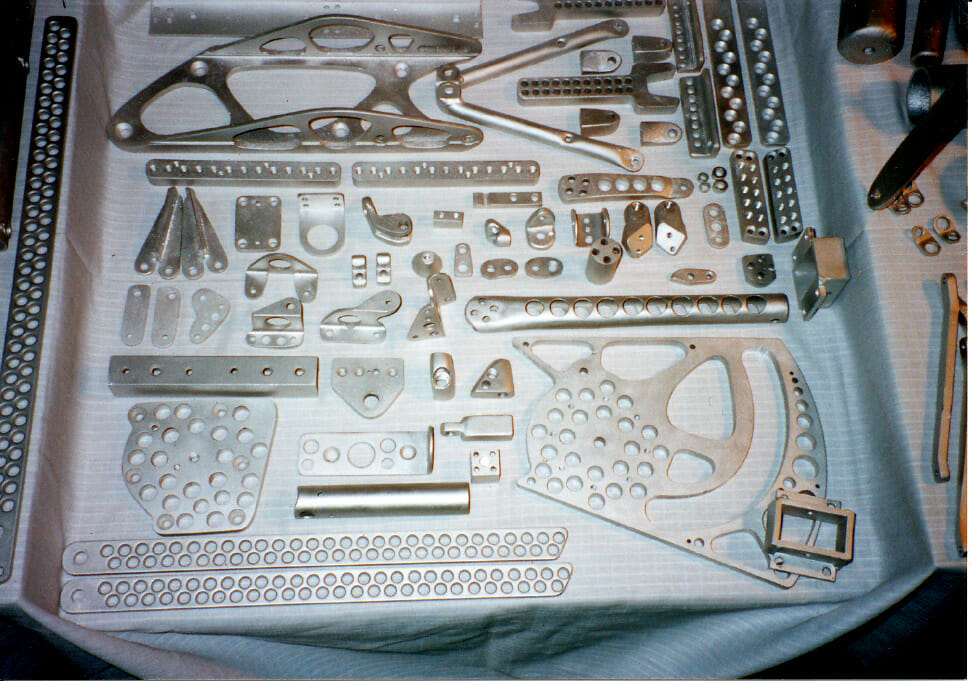

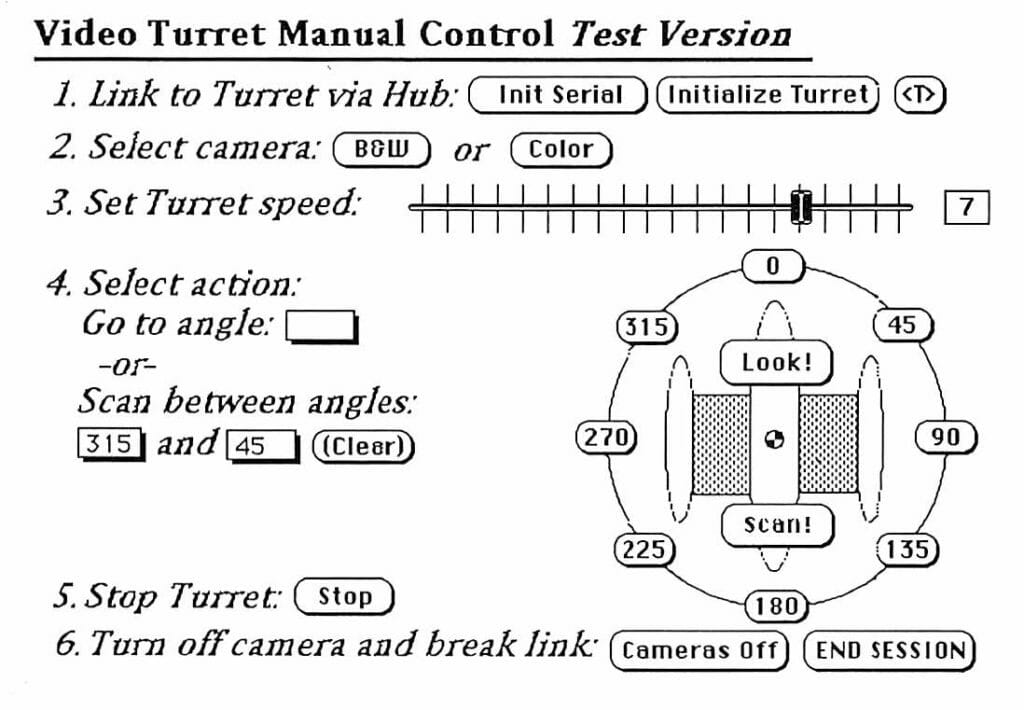

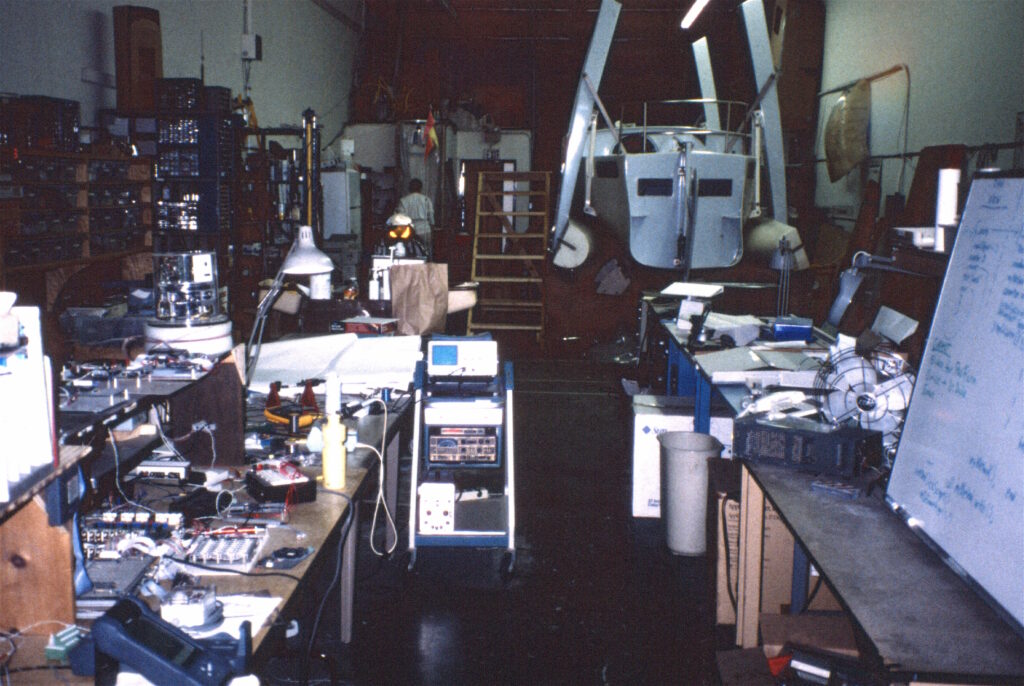

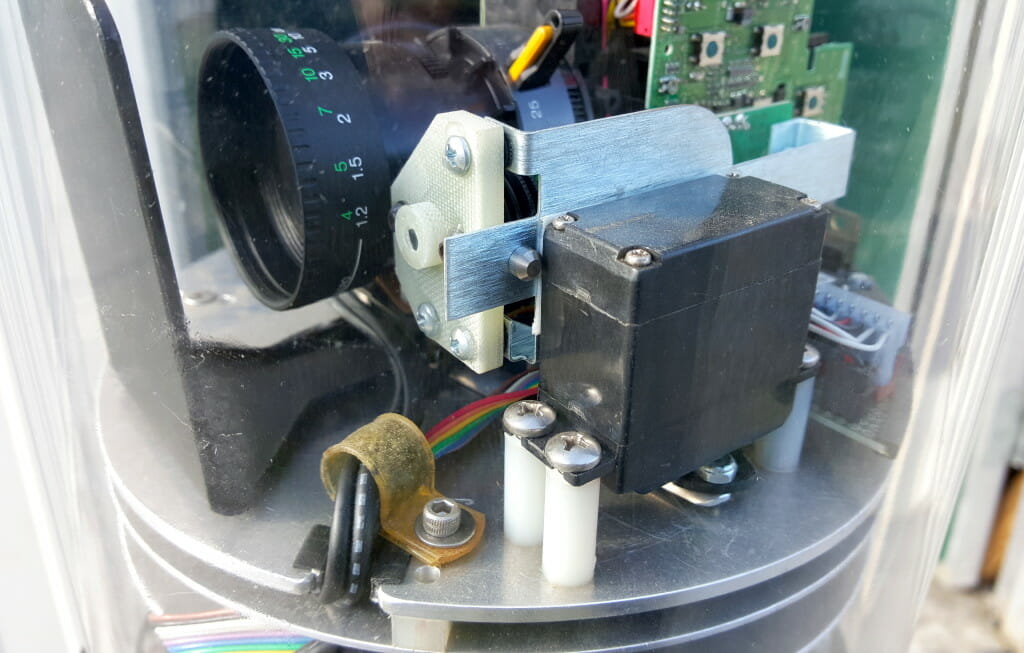

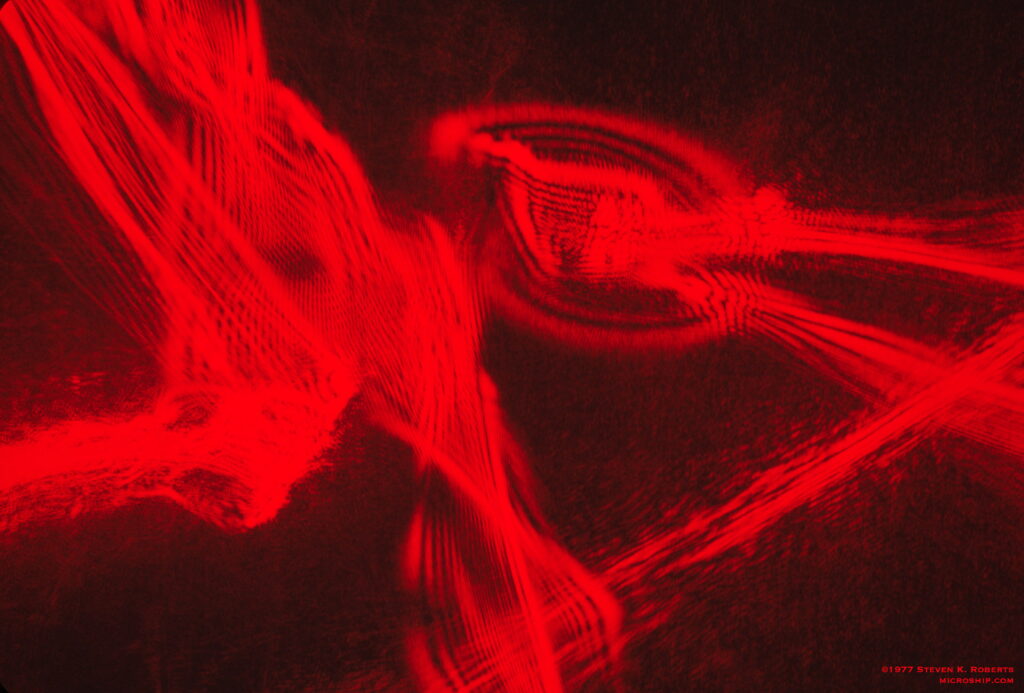

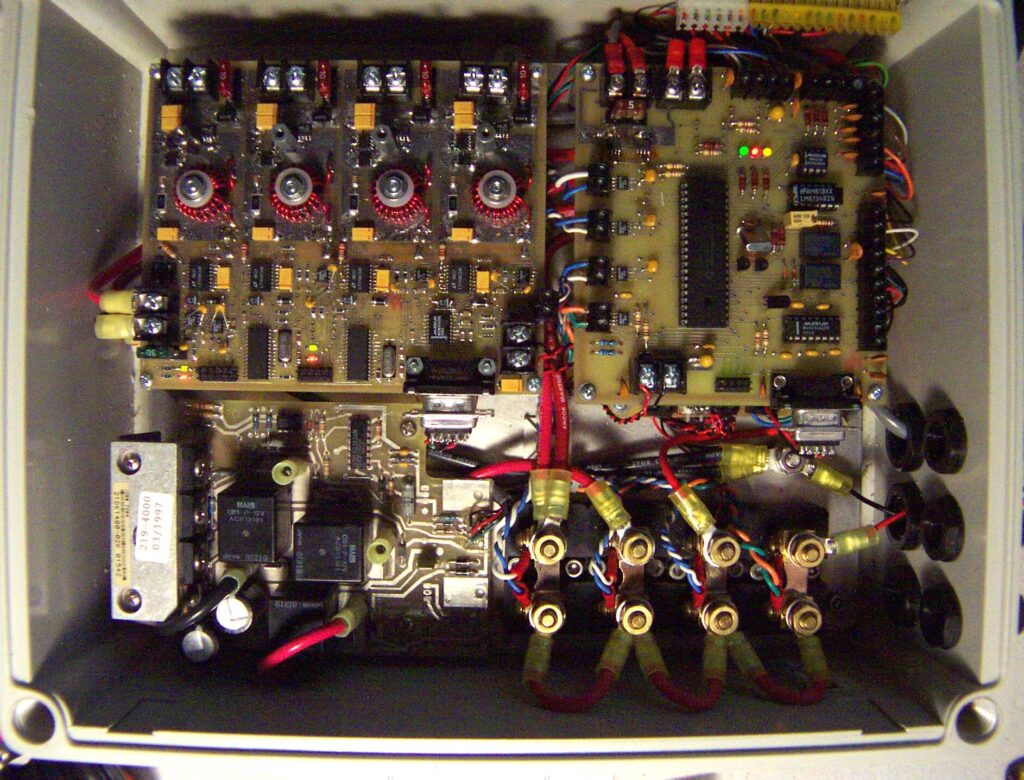

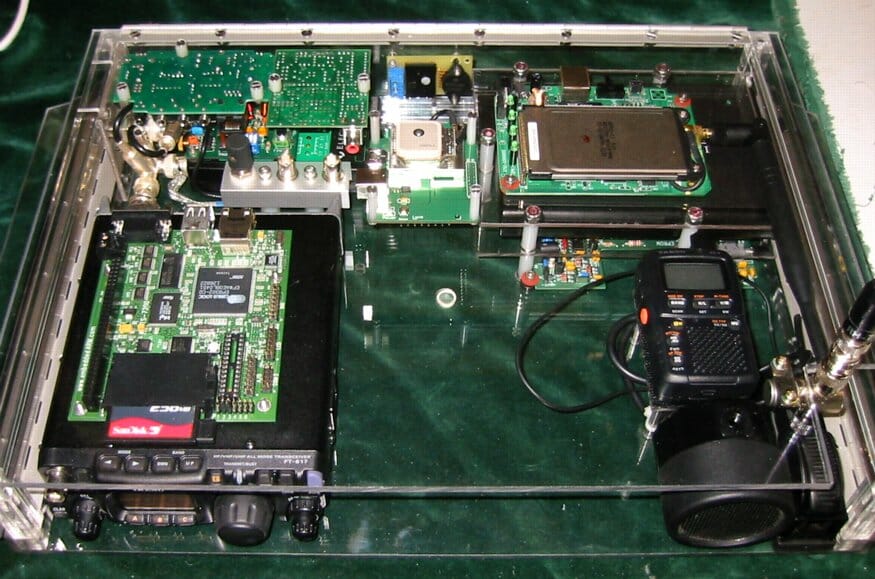

Nodes were assigned to any processing task that could be clearly defined, and some of the student teams produced decent work. The audio, serial, and video crossbar networks all flickered to life, collectively forming Grand Central Station. A couple of shy fellows, uncertain of their abilities, managed with a little coaching to decode the communications between a Sony DAT recorder and its remote control, then replicate it to allow software to drive the unit. (“This is the happiest moment of my life,” one said as they arrived, newly confident, to give their final report in suits and ties.) A delightful trio successfully took on the Manpack project, a backpack-scaled miniature of the Microship itself that would extend the system’s capabilities to peripatetic crew, linked by wireless modem. And after a couple of failed attempts, we found two guys to design the controller for the boat’s video turret with its steerable high-quality camera: Working with a wizard student from the Mechanical Engineering department who single-handedly designed the packaging and mechanical hardware, they conjured a stunningly beautiful piece of work that survived all the technological attrition of the ensuing seven years and became part of the final system. These were the exceptions, the people I’d hire in a heartbeat, and they made it all worthwhile. Here’s a photo essay of Microship electronics, much of it done during this time.

Other projects weren’t quite so successful. The first attempt to write a GUI for the crossbars took two guys two quarters, yielding a fat listing of impenetrable C code for a ‘286 that talked directly to the display drivers. It never really worked, but the fault lay with my vague specifications; exasperated one afternoon, I sat down, learned HyperTalk, and wrote a Mac-based front end in about six hours. Some teams never got past their initial learning curves, and one pair working on power management turned their final report into an explanation of the Field-Effect Transistor, complete with characteristic curves and massive amounts of replicated library material, counting on the ancient tradition of BS to carry the day. Another fellow fried the fuse in my beautiful new Fluke digital multimeter trying to measure the current capacity of a power supply by measuring across it; I sent him on a quest for a replacement with the explanation that one of the first requirements of engineering is knowing how to track down parts. Someone power-cycled my Tektronix scope with every measurement; someone else cut a live multi-conductor power cable with diagonal cutters and made the sparks fly; yet another wired a fully populated DB-25 with about a half-inch stripping on each wire, rendering it virtually untouchable without causing a short. And I’ll never forget, “Steve, do these colors on the resistors really mean anything?”

But you know, it was worth it. The students who passed through the Microship lab learned that there’s a hardware side to electrical engineering, and some of them contributed useful designs to the project. It was all time well-spent.

While all this was going on, the boat itself kept changing shape. It was difficult enough to wean myself from the BEHEMOTH effect, but with the intoxicating new array of essential tools available in the marine marketplace—chart plotters, radar, scanning sonar—it was inevitable that I would start running into space constraints. I think it was the recumbent that pushed me over the edge… a trimaran is hard to paddle with crossbeams and outriggers in the way, and my feeble arm muscles are wimpy compared to these hefty road-hardened quads, so a central design goal became the addition of a pedal-drive system. But why invent this from scratch, when people have been building bicycles for over a century? I acquired an aluminum Linear recumbent and, quickly concluding that it wouldn’t fit inside a kayak of any scale, went to work with a hot glue gun, 2×4’s, and a pile of cardboard to kluge a test platform for my embryonic human-powered boat.

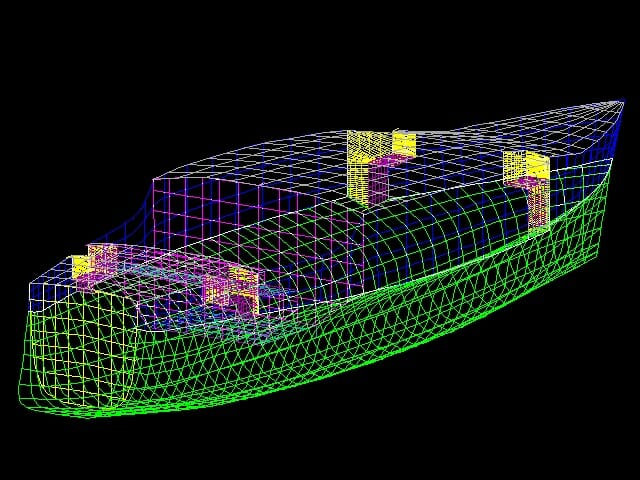

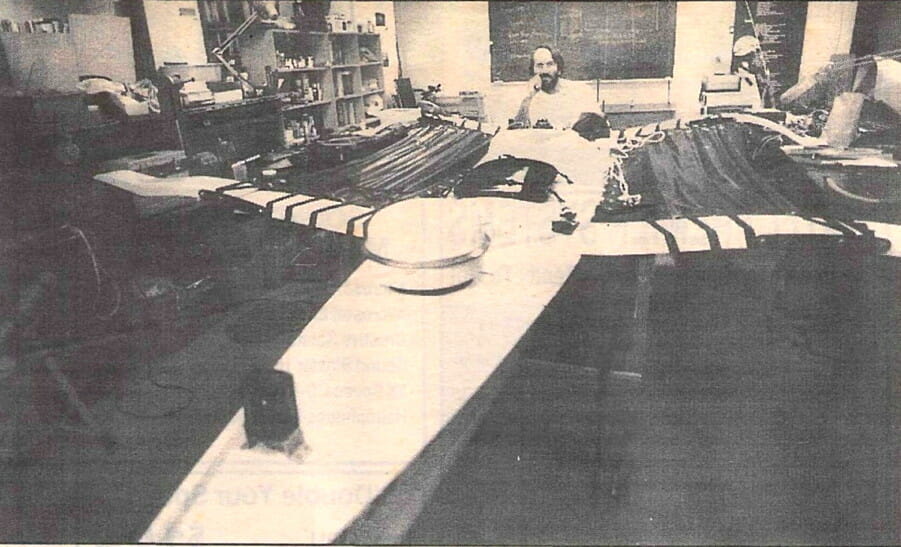

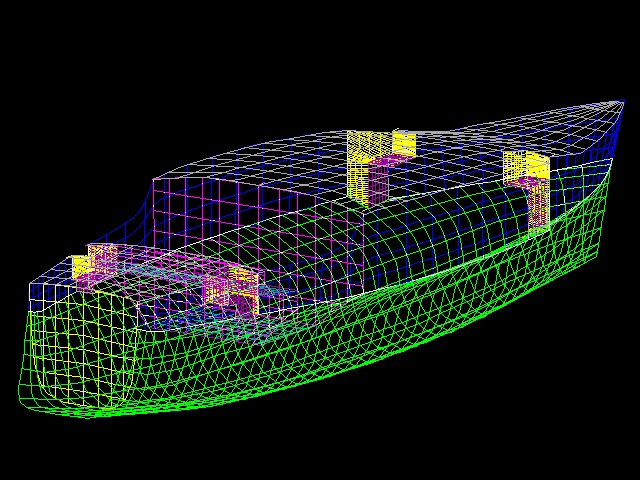

The lab was soon dominated by a huge center-hull model, big enough for an internal hallway of facing equipment racks and a drop-in recumbent bicycle fixture. The plan was to interface the pedals with a jackshaft, linked via clutches to an integrated motor/generator and the propeller—thus allowing either pedal or electric power to drive the propulsion system. Meanwhile, the outriggers had expanded into double kayaks, and two of them were fabricated by Current Designs and delivered to our storage facility at Scripps—their hull-deck seams unfinished to facilitate structural modifications. Things were growing ever larger, and every level of acceptance made it easier to move another step closer to a yacht. At this point, the design assumed a custom 30-foot center hull with 4-foot beam, a full-time crew of two, a head, and integral berth spaces that could be converted to seats to allow flexible watch rotation. A very detailed article about this stage of the design appeared in the February 1994 IEEE Potentials magazine, including a diagram of the multidrop network of FORTH nodes:

One day I found myself sketching a system that incorporated commercial RV-scale camping gear with massive hydraulically deployed outriggers and pushbutton conversion into diesel-powered road mode… a sort of Winneboato. Something was about to snap, all those sexily blinking networked FORTH nodes in the lab notwithstanding.

Microship 2.0—The Fulmar Interlude

The ‘94 crop of students was due in a few weeks. A lot of progress had happened in a year, but the nautical substrate was getting weirder, bigger, and more abstract than ever—even with first-rate consultation from some of the most noted marine architects in the industry. “Do a weight study,” they would say, needing centers of gravity and other hard data. “Tell me the constraints and I’ll adapt,” I would reply. We ran finite-element models on the Cray, hot-glued toothpick and cardboard miniatures, and contemplated internal tubular space-frame construction to support the growing list of non-nautical requirements like modular bicycles and deployable landing gear. The simple fact was that I had encountered the limitations of my original kayak-hacking approach, but didn’t want to move to a yacht despite the bloating of the design to accommodate my growing wish-list.

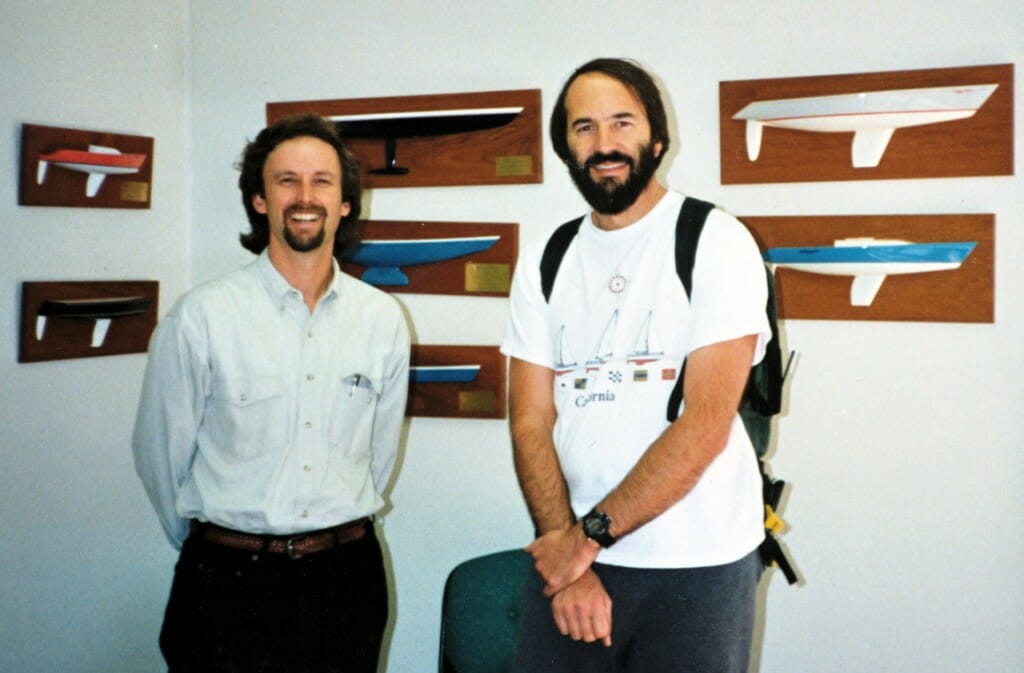

But an intriguing little boat had caught my eye at the Sea Kayak Symposium in Port Townsend, Washington—a 19-foot trimaran called the Fulmar, complete with pedal drive and 80 square foot roller-furling loose-footed sail. I made a jaunt up to Seattle to take a closer look, and decided, during a thrilling test sail in perfect winds, to fast-track this project and just buy the damn thing. It had been over two years since the Microship notion had first burbled into my head, and I was anxious to get on with the adventure. I no longer wanted to be a boatbuilder.

Grinning ear-to-ear, I returned to USCD with the Fulmar on a trailer and immediately launched the wildly amusing project of hauling it up the outside of the engineering building to the patio outside my third-floor lab. This involved 800’ of line and two block-and-tackle assemblies with six-part purchase… not to mention a bevy of students, massive lifting davits clamped to a fourth floor railing, video documentation of the whole affair, and the inevitable parking ticket (for every action, there is an equal and opposite UCSD parking regulation). By midnight, the little trimaran was in my lab on a workstand, and I was staring down the barrel of severe physical constraints.

Yep, this thing was tiny. My primitive weight-study database lost about 1,400 pounds of fat on the first pass, and there was still too much stuff to fit into the boat’s gear hatches. Everything came under scrutiny; about a half-dozen FORTH nodes were summarily tossed, the rest adding tasks to handle the increased workload. Once-essential subsystems lovingly conjured in the UCSD lab were eliminated without a backward glance, wish lists were trimmed to the essentials, and the project lifestyle was scaled back from cushy to spartan… right where it started. I was reacting violently to the fear of feature bloat… I wanted to go, not spend years in this increasingly oppressive lab.

At this point, a romantic event occurred in my life: I met Faun, and a week later we were living together and planning a shared Microship adventure. What better way to field-test this new alliance than spend a couple of weeks on the water? We spent a month or so outfitting the Fulmar with the basics—nav lights, GPS, marine VHF, battery, small solar panel, power management system—and threw together a basic suite of camping gear. We careened back up the coast and borrowed an identical boat from Cy Hernandez in Seattle, forming the world’s largest fleet of Fulmar-19 trimarans (only about 15 had ever been built), then took off on a gonzo 2-week expedition around Puget Sound: the first actual reality check of the Microship concept.

If I ever needed proof that armchair sailing is but a mild distraction compared to the real thing, this was it. The adventure was a rollicking exploration of life aboard tiny boats. Learning curves were many and varied, ranging from the complexities of navigation in an area beset by interesting tidal currents to the fundamental practical issues of living out of dry bags stuffed with gear. We pulled an all-nighter on the first leg, busting our butts to make it to Port Townsend by the next day at noon for my talk at the Sea Kayak Symposium, spending the wee hours screaming north through Admiralty Inlet in a shipping lane in the fog only to round Marrowstone Point and pedal all morning against wind and current. We beached hard in dumping surf, stranding ourselves for the night in howling winds on Dungeness Spit. We pedaled 20 miles across an uncharacteristically calm Strait of Juan de Fuca, entering Victoria Harbor at midnight, then meandered all the next week through the San Juans, coming to rest at last in La Conner where a shear pin in Faun’s pedal drive unit failed during an encounter with kelp, rendering the boat useless without a haulout and a bit of shop time. It was an adrenaline-intensified romantic getaway… and utterly impractical.

The problems, in retrospect, were obvious. A prominent centerboard trunk that carried the crankset made it impossible to lie down inside the boat, and the saggy trampolines between the hulls were too low and wet to be of more than recreational, fair-weather value. No sleeping on the water, in other words… yet beaching was only possible in benign conditions—dragging the 500-pound loaded boats across rocks would strip the gelcoat and gouge the hull, and even on sand it would take significant help to overcome friction. They were too heavy to drag above tide line, yet impossible to sleep aboard… so how would we handle the daily fundamental logistics without having a truck and trailer meet us at every stop? On tiny Blind Island in the San Juans, we picked up a mooring buoy, then raised a nearby sailboat on the VHF and schmoozed dinghy rides to shore. In Victoria, we luxuriated in an overpriced marina, paying by the foot the same nightly rate as a cozy 38-foot yacht, yet we had to hoof it to town and find a place to crash. In Sequim Bay, we put up a tent in the marina, but were admonished to clear out by dawn or the harbormaster would throw a fit. Practical problems dogged us daily.

Was the whole concept of small-scale aquatic technomadics fundamentally unsound? I packed the boat back on its trailer and headed back to San Diego to figure out what next.

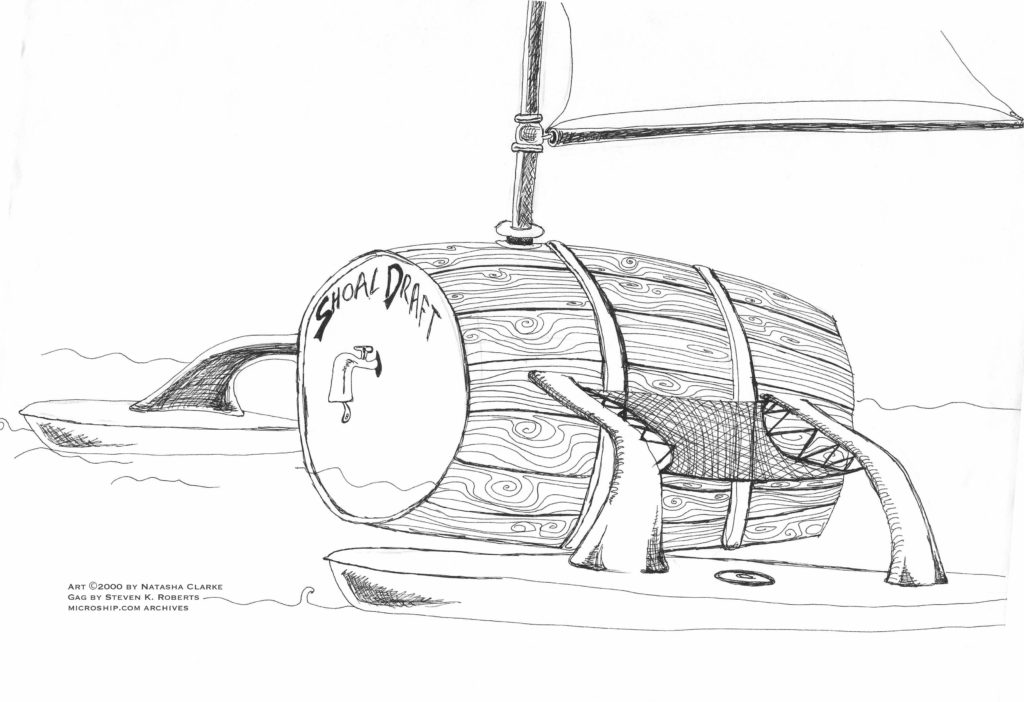

Microship 3.0—The Hogfish Era

Convinced that the only solution to the stated practicality issues lay in moving up to a trailerable pocket cruiser, we returned the borrowed Fulmar, put mine up for sale, and embarked on the quest for an affordable multihull that could accommodate my monstrous wish list of technology while providing enough room for two people to live aboard. By early 1995, we were hot on the trail of our next substrate as the second announced departure date quietly passed… once again forgetting the original motives that called for a bicycle-scale, human-haulable, sleek little boatlet.

I flew to Texas to sail a whizzy Stiletto, talked to sellers of 25- to 35-foot catamarans and trimarans across the land, and collected study plans from noted multihull designers. We clambered about a huge clunky MacGregor 36 “on the hard” in a dusty boatyard, sketched interiors, made cardboard models, and found ourselves gravitating toward a Hughes 30-foot cylinder molded “tube cat”… only to discover after chalking a hull cross-section on the wall that it would be like living in a parallel pair of narrow tunnels. We backed off, recognized the structural advantages of a tri, and homed in on a Marples Seaclipper—something that could be homebuilt of plywood and epoxy. But the 2-year, $25,000 investment necessary to arrive at the start of electronics packaging was, despite no-doubt interesting learning curves enroute, a daunting reality. The calls and research continued. Somewhere there had to be a boat that was complete enough to give us a head start but not so complete as to be unaffordable.

I was speaking one afternoon with Mike Leneman of Multihull Marine in Marina del Rey, and he was explaining that what I obviously need is an F-31 “kit.” For only $52,000, I could buy a sleek folding trimaran shell with no interior or rigging… and hey, it comes with a free trailer! I chortled, wincing inwardly at the thought of my bank account, and told him that I’m a freelance writer who has managed previous technomadic projects through the twin miracles of sponsorship and industrial scrounging. I gave him a capsule summary of BEHEMOTH and the Microship, and was about to hang up.

“Wait!” he cried. “I have your boat right here!”

$5K later we were the owners of an eccentric boat dubbed Hogfish — a precursor to the F-31, built by John Walton and Mike Michie in 1983 just before they started Corsair Marine. It used the nifty Farrier folding system, and had been fabricated by folks for whom money was no object: carbon-fiber crossbeams, Klegecell-cored S-glass/epoxy composites, Lewmar hatches, aft cabin, custom hardware from stem to stern, and (originally) a carbon wing mast fabricated by the legendary Burt Rutan. But Hogfish had spent the past few years languishing on a rustbucket trailer in a graffiti-decorated Los Angeles storage yard, and as I hauled the swaying mass gingerly down I-5 to San Diego, I felt like I was pulling a jailbreak

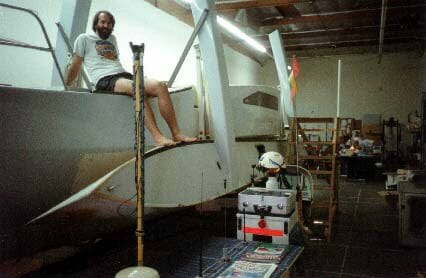

Even though we had no place to work on it—certainly not the third-floor lab at UCSD—we were convinced that this was the solution. Control and front-end systems continued to evolve on the bench as more students took on projects. Now and again I would make a pilgrimage to the boat, sometimes accompanied by a marine architect or rigging wizard who would hold forth as I made notes. But the TO-DO list on the substrate itself was outpacing my available time, skills, workspace, and funding.

Before long a new problem emerged—the inevitable loss of the UCSD lab. We embarked on another epic cross-country combination speaking tour and space quest, making inquiries so similar to those of 1993 that they have all run together in my memory, and from a pay phone in a Key West bar learned that Apple Computer had come to our rescue by leasing a 2,000 square-foot building for us in Santa Clara. Instead of making occasional pilgrimages to visit Hogfish in a dirty overpriced storage yard, it would become the centerpiece of our living and working space! Although it was a windowless, noisy, fluorescent-lit, relationship-stressing concrete tomb under the San Jose airport departure path, it was perfect in a twisted way (and free). We hauled Nomadic Research Labs up the coast and moved in.

By February of 1996, we were immersed, making sluggish but steady progress on a rotating deck-stepped 40’ sloop rig and essential fiberglass structures, while continuing to refine the on-board network and control tools: video turret, crossbars, data collection, and graphic front end. But something fundamental was missing and I was loathe to let myself see it. It shows in this video; there are lots of cool toys, but the energy was low.

I started getting a few hints of it during the extended breakup with Faun, still more by observing the time I wasted on pointless web surfing, hanging out on CU-SeeMe, and furtively playing computer games. The passion had skulked off in the night through the grime and traffic of Silicon Valley, leaving me saddled with a too-large project that had come to feel like a dead-end job. The volunteer teams that had defined the very heart of BEHEMOTH and the UCSD era seemed to have disappeared entirely; the Nomadness mailing list that is my core network community bided its time, saying little, waiting quietly for completion of the yacht or, more likely, the fizzling of the whole stupid idea. It had simply gotten too big for one person to manage, and it was no longer really my dream anyway—what, me a yachtie? Hell, I couldn’t even refer to the boat as “she.” I never sat in the cockpit with a beer and fantasized misty-eyed about romantic adventure; I just half-heartedly plugged away at a TO-DO list that never got shorter.

I was doing things that I didn’t enjoy to build something that I not only didn’t want, but had trouble imagining. That’s hard to admit when the world is still sending bright-eyed reporters around to do breathless interviews with the high-tech nomad. I pushed my misgivings into the background and kept at it.

Microship 4.0—Embarking on a Non-sequitour

But in the Spring of 1997, with Faun gone, continued Apple funding uncertain, expenses skyrocketing, keynote bookings down, and the IN-DEEPER basket more intimidating than ever, my world changed completely.

It was Sunday, March 23, and I paced the lab like a caged animal, constrained to a windowless rectilinear space with artificial light. Vague dreams of unrealized aquatic adventure were driving me to odd behavioral sublimations; long-forgotten urges burbling deep in my reptilian brain.

At the center of the lab stood the Icon of the Dream, covered with dust, tools, respirators, Shop-Vac, and the funky detritus of fiberglass hackage. Surrounding Hogfish on all sides were cluttered benches, shelves laden with expensive nautical and electronic hardware, uncategorizable clutter, chip databooks, sticky epoxy fixins, a maze of cables, computers, and other stuff—all uniformly coated with gray dust. I paced. I climbed the steps to the cockpit, paused, and descended. I idly picked up the AIR Marine wind generator and spun the shaft to make the LED flicker. I peered through a port into the aft cabin and stared at the battery bank, putzed ineffectually with the flute for a moment, and scanned the “Fiberglass Projects” list densely occupying one of four whiteboards, hoping as always that I could erase something… but no. I randomly picked up the April ‘96 issue of Sail Magazine and thumbed the pages, absently, as one might flick one’s eyes over a rack of postcards at a checkout counter.

Understand, we’re talking major restlessness here. A half-decade in Microship labs or on a quest for same; the bike (now the world’s most expensive boom box) wailing the blues while mercilessly taunting me with road-dirty wheels and a design optimized for movement. Ah, memories. Feeling like an old timer lapsing into reverie, I ignored the relentless itch of instincts unfulfilled, consciously turned my back on the TO-DO list, slumped on a lab stool, and started browsing the magazine.

Ah yes, that article. One of my favorites—the comparison of “sailing kayaks”: the familiar Fulmar 19, the fast rotomolded WindRider, the Balogh Batwing, the racy foiled Triak, and the pretty wood Chesapeake Light Craft SailRig—all sleek, light, fast, exciting little boats. <sigh> Aching images of the Fulmar adventure with Faun bubbled past my barnacled brain as I read the piece again, lingering on the pictures, recalling the fantasy that started all this back in 1991, pedaling BEHEMOTH up the Wisconsin shore of Lake Michigan while daydreaming about gizmological boatlets—but no, no, stop thinking about that! I’ve been there; the Fulmar was too small, THIS is the boat, this is the boat I have to finish NOW. I looked, almost guiltily, at Hogfish and felt… nothing.

Wow. Never really noticed before, but gee, now that I thought about it… I really haven’t had much of an emotional connection with this boat, have I? It (not she) is a good logical solution to the stated design goal, which had something to do with a trailerable platform for a happy couple on the technomadic adventure trail. But what about the passion, the heart of this whole project? Suddenly alert and suspicious at the scent of Major Change in the air, I stared at the boat, then back at the magazine… then back at the boat. The toggling between adrenaline and yawns was too obvious to ignore, and I was instantly embarrassed that I hadn’t noticed this a year earlier.

Five years in the lab had turned me into exactly what I fled so long ago, while out there, not really so far away, were quiet coves sparkling in the moonlight, mist-shrouded rivers sussurating through canyons of naked rock and verdant green, sun-splashed beaches that beckon like eternal visions of idyllic summer vacation, campsites abuzz with chittering and aglow with firelight, those first long swallows of cold beer after an all-day haul, the spark of delight in the eyes of a suntanned friend, the rush of a reach that hardens the sail and foams the wake, the magic correlation between dead reckoning and a fix, the astonishment of a satellite email packet, the crackle of a ham radio contact in the wilderness, the delicious incongruity of backlit LCDs during a night sail, the tales that fly when nomadic spirits recognize each other and pause to share the calm moment of sunset, the adrenaline-pumping madness of nature’s fury, the love, the joy, the perspective, the living…

Maybe big boats make more practical sense, but I didn’t care. It was time; ancient urges were surfacing in a sort of Spring Fever of the Soul. Life was passing; pheromones were in the air, restlessness in the night.

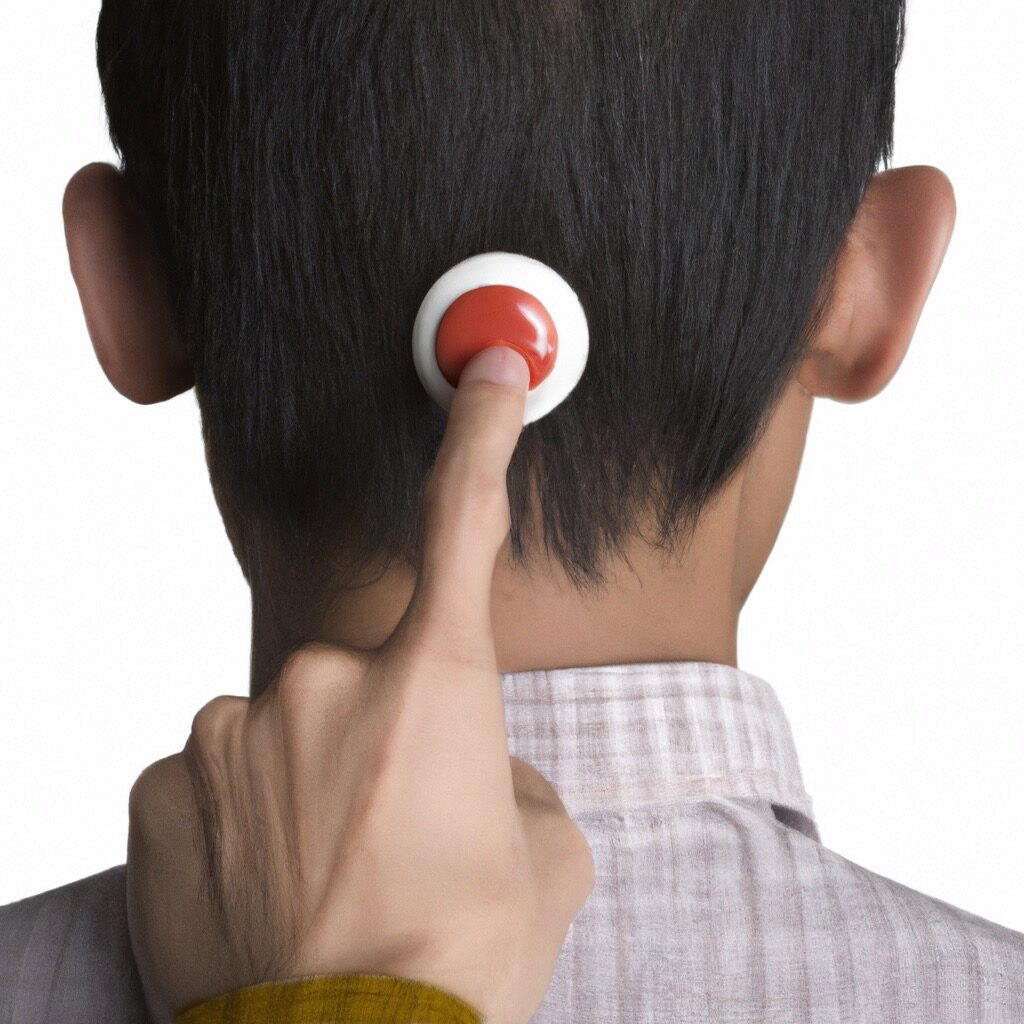

Without a moment’s hesitation, I reached around to the back of my head and hit the reset button.

Wordplay and Songline

In a rush, the original fantasy returned, not without a bit of deja vu: “a full-scale technomadic overlay onto a tiny nautical substrate, elegant and swift.” Seems I had said those words before. Looking back at the feature bloat and compounding complexity that had somehow eclipsed the sleek little kayak-based design, I cringed with embarrassment at how easily I had become caught up once again in The BEHEMOTH Effect, even though I had recognized the phenomenon clearly enough to give it a name and joke about it in my online Microship status reports (of which there had been 119 by this point).

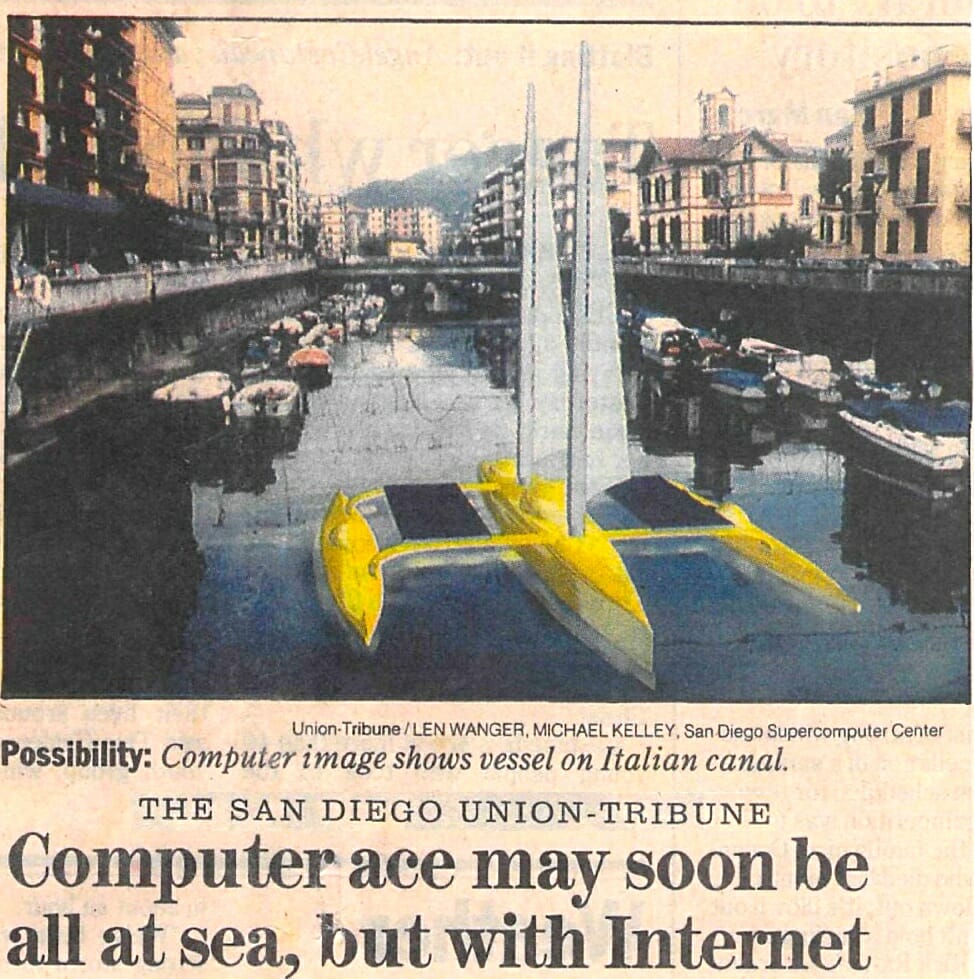

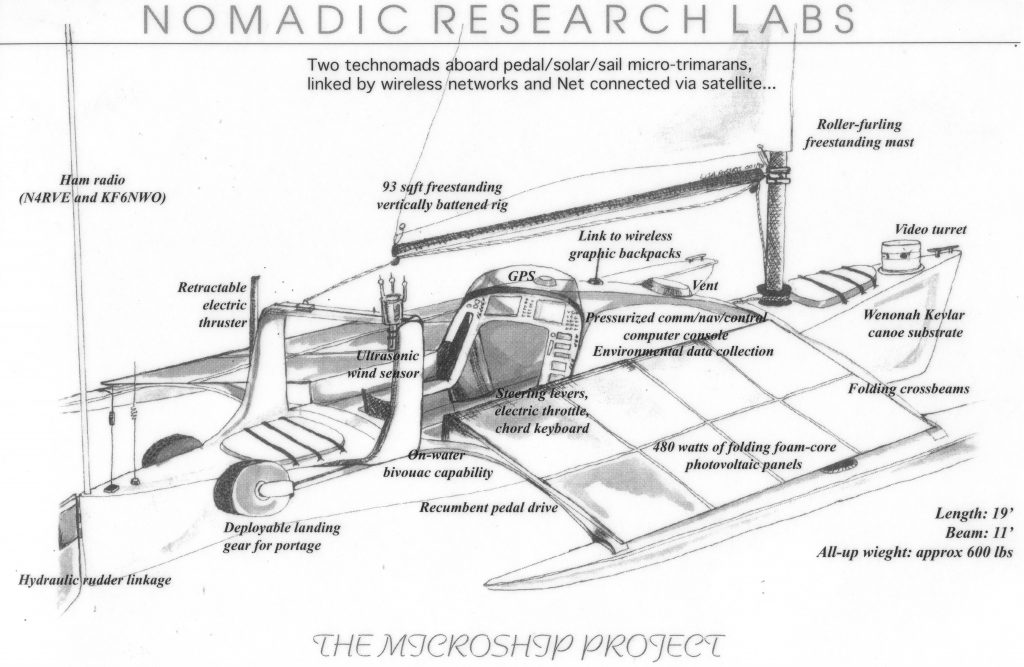

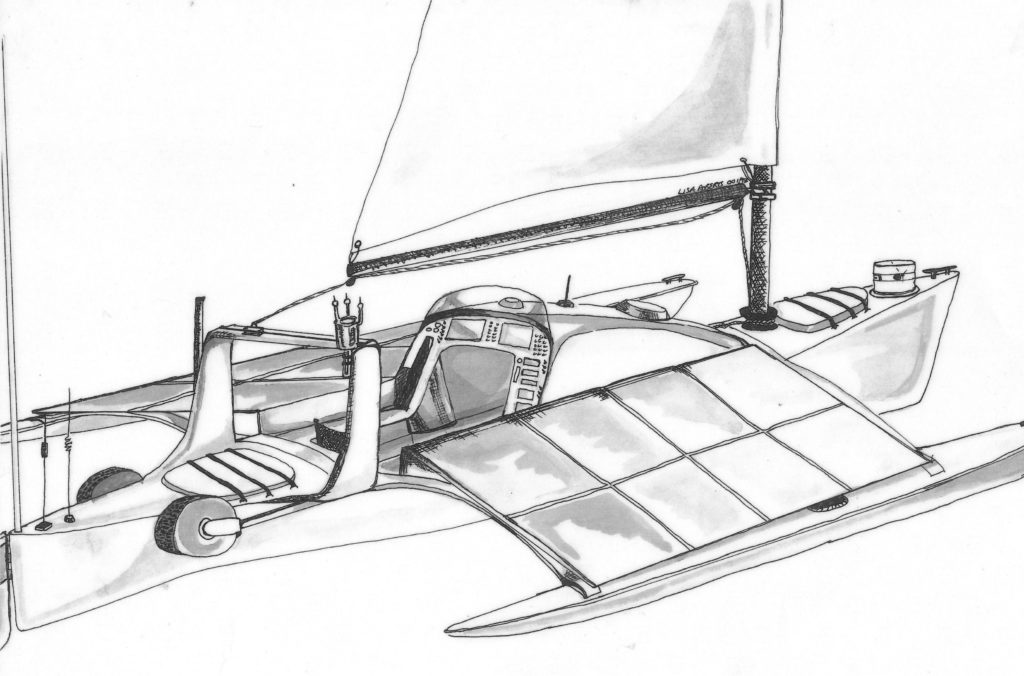

Within days, I had a clear design goal: a pair of canoe-scale micro-trimarans with pedal, solar, and sail propulsion. There would be enough room between the bulkheads of each boat to retract the seat and sleep aboard, deployable landing gear would allow unassisted haulout and “road mode,” and all electronics would be embedded in a single control console. Everything else was scaled to fit, from the sensor suite to life-support tools, and I was startled to discover that even though I was restarting almost from scratch, the TO-DO list was shorter (and cheaper) than the corresponding one associated with Hogfish. And although I feared that my online readers would throw up their hands in exasperation at yet another fundamental change of direction, I was amazed to receive over 80 congratulatory emails within a week of posting the announcement… and only one telling me I was insane to consider going to sea on anything smaller than a megayacht.

By June the lab was abuzz with energy, more incubator than cage. The proliferation of electronic systems was now capped at a reasonable level, and it actually began to appear that it would be possible to complete this project within my lifetime.

There was another factor adding energy to the equation… the latest episode in my cyclic love life, wherein each wave of passion spills over into my projects and propels them into a new phase.

After initial email contact on the day of the epiphany and 1.2 Megabytes of spirited correspondence over the ensuing seven weeks, Natasha arrived from London and transformed my life. We survived the exhausting period of mutual discovery, found a buyer for Hogfish, and threw ourselves full time into the development of the twin boatlets that were, at last, moving in the right direction. After spending half a decade investigating and discarding various misguided notions, I gotta tellya, this was heady stuff. I could actually smell the salt water, the aroma wafting all the way from Alviso through miles of industrial parks and into our sterile little concrete world.

The energy was back. We used the CAD system to build an actual-size mockup, and I sat in it for hours, enchanted by adventure fantasy far more tangible than I had ever felt in the big boat. Sponsors were immediately responsive to this sleek, human-scale design, and within weeks the essential components were on hand: Wenonah Odyssey canoes, WindRider sail rigs, Minn-Kota thrusters, even a 100-pound roll of fiberglass cloth from my old friend David Berkstresser. We contracted Fulmar (now in Canada) to fabricate the amas and akas (outriggers and floats) and found a local boat builder to make carbon-skinned, foam-core rudder blades. And a human-powered vehicle and composites guru from Salt Spring Island, Bob Stuart, arrived in the lab, bearing one of his Spinfin pedal-drive units and diving in to help on overall design and fabrication.

From BEHEMOTH to the Microships, 6.5-minute video produced by Natasha in 1997

But one last problem had to be solved. Apple was in a downturn, and “non-essential programs” were getting killed off left and right—including the lease on our building. For the last half of 1997, I was thus paying rent on 2,000 square feet in Silicon Valley, something that would have been fatal if it hadn’t been for a few well-timed speaking gigs and the assistance of my father in Kentucky. But now what? A third round of free lab questing had turned up nothing, and damn it, I was starting to want my own workspace, unaffected by politics, corporate priorities, and the economy.

As the end of the lease drew nigh, our world became a bizarre, bifurcated reality of fiberglassing and boxing—Bob’s creative efforts yielding ever more interesting results even as the workspace collapsed around him and his intrepid apprentice, Natasha.

“Where are those neoprene strips you found?” he asks, looking for gasket material to use on the hinged console cowling.

“Ah, just a second.” I scan the moving inventory, already cataloguing the contents of over 200 boxes, find the reference to carton number L-13 (a plum of a Silicon Valley dumpster-diving prize—thousands of identical strips of the stuff, cast off by some anonymous corporation), and after a few moments’ scurrying slit the tape, tease out a few, and thread my way between packed piles and the Zone of Goo to pass them to Bob.

Work continued in this convoluted fashion until the twin mega U-Haul fuel guzzlers rumbled into the parking lot and cozied up next to the Mothership, their gaping maws all in a row, ramps lolling like tongues, hungry for boxes and lab furniture. In one nightmarish weekend, we optimized packing density to the point of exceeding legal weight limit specs and hit the road… a convoy of three trucks and two trailers held together by walkie-talkies, with 26 wheels on the ground and an aggregate fuel economy of 2.5 miles per gallon.

We aimed ourselves at Bellingham, Washington for no good reason other than having a vague affection for the town, shoveled everything into two huge units in a self-storage facility, and rented a room on Christmas day with three young folks who never did quite figure out what we were all about. The next two months were a blur of house-hunting and crawling through tunnels in our frozen possessions to extract essential bits; although I did manage to bang out a couple of articles for Dr. Dobb’s Journal and CQ VHF, I was starting to wonder when we’d again be slinging epoxy and gearing up for adventure.

Nomad is on Island

Desperate to get back to the project, we considered everything from a falling-down old shipyard in Blaine to a musty barn with crashable loft and rentable doublewide, but instead fell into a 6-acre slice of sociobotanical nirvana on an island in the Olympic rain shadow. We moved into a well-insulated little house and erected a 3,000 square-foot pole building back in the woods, with a hushed 1/8-mile sylvan commute connecting the two. It still seems dreamlike and surreal, even though I’m writing these words four years later in that building nestled deep in the forest, with crisp MP3s pouring from USB speakers hanging off my iBook and Java-the-cat purring on my lap. It’s strangely circular, becoming a homeowner to facilitate the resumption of nomadness.

Camano Island is an 18-mile-long dongle hanging between Whidbey Island and the northwest Washington mainland. It is linked to the latter by a bridge to Stanwood at the north end, rendering it a strange blend of relaxed island mentality and drive-on convenience. We’re on the west side, close enough to the shore that we can see across Saratoga Passage from the house and walk amphibian boatlets a mile to a public launch ramp for test sails and mini-expeditions.

The house is a tightly-engineered structure with passive solar heating (actually useful sometimes, despite what you’ve heard about the Pacific Northwet). The interior has an open-beam ceiling, red-oxide tinted slab floor, and galley-style kitchen with a glass wall to the solarium (the hydroponics, dehydrating, and vacuum-packing facility). There’s a Danish woodstove, propane-fired radiant heat backup system, a Japanese soaking tub we never use, and one-foot-thick R-40 structural foam panels comprising the ceiling. It has won design awards and been featured in Fine Homebuilding (Issue #94). None of this has anything to do with the point of the whole exercise, but having a cozy place to live is rather amusing after years of outlaw camping in windowless labs, cooking on a hotplate and showering in the sink.

The building itself was a weird lesson in economics: the previous facility was an industrial slum by Silicon Valley standards, yet we erected a spacious 3,000 square-foot structure on the island for what it would have cost to rent the same space in Santa Clara for 14 months. In the process, I was dragged deeply into things I know little about, wrote far too many checks for lumber, and sweated over structural and electrical inspections. But at last we turned on computers, organized parts inventory, and stopped thinking about boring stuff like humidity management, stringing power and phone wire through trenches, and how to get a recalcitrant bundle of electrical cable around the overhead door.

The lab is a 40×56-foot “monitor-style” pole building with a second, narrower floor as wide as the space between the two inner rows of poles. This gives us about 750 square feet of office space separate from the gritty realities of the lab below, with a stairway along the back wall emerging into the “gear room.” A large central area comprising three bays is the place for video production, publication of technical monographs, conjuring fabric projects on the Sailrite machine, and the Nomadic Research Labs business office. Winding through this is the path to my little sanctum sanctorum, a carpeted nook where I write, schmooze, and surf.

But the real action is downstairs. I went on a bench-fabrication frenzy, integrating 180 square feet of permanent workbenches along the walls in the Zone of Hackage. All this is adjacent to my boat bay, allowing a long in-utero system packaging phase without driving everyone crazy with dangling umbilici. The other boat is in dust-controlled space (complete with industrial air cleaner) adjacent to the fiberglass shop; remaining lab space is given over to the workshop and a huge wrap-around Hall of Inventory that segues from hundreds of small-parts drawers to a rank of shelving units and on into the tool crib and stand-up racks for sheet stock. There’s a drill press, table saw, sheet-metal brake/shear, belt sander, grinder, and the usual tool-strewn benches for dirty work. And near the front door, Miss Piggy (the woodstove) helps chase the northwest chill—as long as I slavishly devote myself to keeping her fed.

The only irritating problem was that I could no longer blame the environment for low productivity. Having a sense of long-term home was a bit weird, for a nomad, but I tried not to let it get to me… although I became involved in an environmental group and found myself writing letters to the county and the local papers whenever action had to be taken against the ravages of irresponsible development or commercial logging on our fragile little island. We even bailed out of NASDAQ just in time to rescue the adjacent five acres from some idiot who wanted to clear-cut it and put up a double-wide with the proceeds. (In the long run, land purchase was cheaper than homicide.)

It’s a pain to care about a place, but nice to have a place to care about. And something beautiful began to emerge.

R&D in the Boonies

Once this infrastructure was established, it was at last possible to get back to work without fretting over future lab upheavals—but one lingering problem remained. How could we achieve a critical mass of development energy out here in the woods, on an island far from the geek culture of Silicon Valley and teams of grade-motivated engineering students?

Not surprisingly, the Internet held the answer. It’s difficult to recall a time when there was not a vast, globally distributed resource of brains a few mouse clicks away, but when I was building the Winnebiko, my “intellectual support” network was limited to a few friends in Columbus, Ohio. Now, we had brilliant software developers and volunteers whom I’d never even met

Every couple of months, I would post a Microship Status Report to the Nomadness mailing list. These updates, usually quite technical unless there had been a recent adventure to eclipse the geeky bits, constituted the ongoing narrative of the project; quite often, along with the tale of recent developments, I’d toss out a question or wonder aloud about something. By early 2002, there were an estimated 5,000 people who read each issue, and it had reached the point where any puzzle, no matter how obscure, would be solved almost immediately. Coupled with Googling my way to websites and Usenet archives, it pretty much reached the point where any technical question could be at least partially answered within a few minutes (usually with lots of interesting side trips enroute).

But that still didn’t distribute the workload. To accomplish that, we created a casual but effective volunteer program, including the ever-popular “Geek’s Vacations.” Every now and then, someone would become interested enough in the Microship project to take a break from their real job, travel to Camano Island, and live with us long enough to bring a new system online or solve a challenging design problem. We’d provide food, espresso, beer, and general amusement. They’d provide genius. When you add the remote volunteers who write code at home, the Open-Source development community, and a team of 50 or so consultants ready to brainstorm ideas whenever I called with a question, the result was a formidable brain trust that most companies would kill for. It’s a shame that my management skills still sucked, but somehow we muddled through.

Some people even moved in. Bob Stuart was a regular fixture for quite a while, applying his formidable mechanical design and fabrication talents to the epic landing gear project, fiberglass shaping, and just about every structural component in my boat. Ned Konz dropped by for a brief visit at the tail end of a recumbent bicycle adventure around the Western US, and stayed for 3 months to get me properly inculturated in Linux and do the initial design of the control system. Tim Nolan came from Wisconsin to develop the entire power-management system. And Natasha, before jumping ship to pursue her own dreams, applied Bob’s gentle coaching and her own liberal supply of elbow grease to build the sistership, Songline.

It was still remote and often lonely, but the project moved forward as long as there was motivation to drive it. So what about the more mundane issues, like acquiring parts? In Silicon Valley, I could hop in the truck and be happily prowling the musty aisles of world-class electronic-surplus emporia within minutes.

Again, technology to the rescue. Any data sheet I want is stashed out there on the Web as a PDF; anything I need to order, however obscure, is available. The ultimate hardware store, McMaster-Carr, is not only way better than anything within 100 miles, but I can have the stuff delivered by UPS the next day. Electronic parts? In the old days, the only sources of the latest goodies were stuffy distributors and smarmy manufacturer’s reps who only wanted to talk to Big Accounts; other than that, we were stuck with the tired old catalogs and mail-order surplus. But the world has changed; it’s now a simple matter to find even the most esoteric RF connector or surface-mount miracle chip, download the data sheet, crank out a PC board, and have it blinking in a day or so. Boonies? What boonies?

So. We finally had it all: a stable Microship design goal, spacious facilities, smart people, unlimited information, and access to parts. It was time to get to work.

Four years passed. It was a blur of fiberglassing, wall-staring, knuckle-busting, grinding, painting, sanding, machining, anodizing, welding, wiring, testing, rebuilding, researching, and rebuilding some more… and it took its toll on relationships, finances, and sanity. If you want to relive the whole bizarre epoch, you can read all about it in the Microship Status Reports of 1998-2002—it’s actually a rather amusing tale, assuming you have a twisted sense of humor and an enduring voyeuristic fascination with unfolding complexity, wrong turns, gotchas, oh-shits, by-the-ways, and the countless other nightmares that characterize any attempt to engineer your way around a moving target. This excellent piece in Make: magazine really nails it.

And then… with the traditional nautical perversity of boats, my own physical needs began to shift just as the end was in sight. By 2006, I’d be single-handing a Corsair 36 trimaran (“Microship on Steroids”), then going to the Dark Side a year later with a 44-foot steel monohull. What a long, strange trip, and all that…

2017 Update

The Microship is seeking a new skipper. Other than a few months in the water in 2013 and a flurry of activity in 2015, she has been sitting in various labs for far too many years. She needs a young geek adventurer to take her on an expedition.

Here are a few more technical details…

Building the Microship Trimaran — The ten-year Microship project left a trail of narratives from which it is difficult to extract a clear picture of what, exactly, lies at the heart of this machine. I wrote this to provide that, leaving out electronics, landing gear, hydraulics, pedal drive, thruster, solar array, sail rig, and other complications.

First Microship Launch — In October of 1998, we got the hulls wet for the first time. This post has lots of photos and a minute of video… rolling the boat on her creaky workstand across the field of Fort Worden in Port Townsend, then down the road to the launch ramp. Doing this with a film crew was audacious, but gave us some lovely footage.

Microship Electronics Photo Essay — Even though much of the electronics developed for the ship is now obsolete (and unnecessary to future expeditions), this gives an excellent look at some of the engineering that went into the project. Today’s tools are so much smaller that the comm/nav and telemetry side of things will be easy and cheap.

Microship Hydraulics — Landing-gear control, ship steering, and rudder deployment all depend on a hydraulic system that allows linear push-pull movement to be routed through cabling harnesses. This piece gives a look at that system.

Microship Revival — In 2013, after a decade of lying idle in the lab, I splashed the boat and kept her for a few months in the Port of Friday Harbor… leading to lots of short adventures. This is the tale of that launch.

Microship Status Reports

The timeline that follows is the collection of postings I wrote during this huge project… with tons of technical details. As of August 2020, this is yet only partly done; lots need to be cleaned up and posted on the server (whereupon they automatically are added to this list). The “Read More” links open in new tabs.

You must be logged in to post a comment.